2528

Individualised perioperative brain growth in infants with congenital heart disease (CHD): correlation with clinical risk factors1Centre for the Developing Brain, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Biomedical Engineering Department, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 3MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 4Department for Forensic and Neurodevelopmental Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 5Biomedical Image Technologies, ETSI Telecomunicación, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid and CIBER-BBN, Madrid, Spain, 6Paediatric Cardiology, Evelina London Children's Hospital, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Neuro, Brain, Cardiovascular

Infants with congenital heart disease (CHD) are at risk of neurodevelopmental impairments, which may be associated with impaired brain growth. We mapped brain volumes from pre- and postoperative brain MRI in 36 infants with CHD undergoing cardiac surgery or intervention to normative curves derived from 219 healthy infants. Perioperative brain growth was impaired, and was associated with clinical and surgical risk factors, including higher preoperative serum creatinine levels, older postnatal age at surgery, longer cardiopulmonary bypass duration and longer postoperative intensive care stay. Brainstem and deep grey matter growth appear particularly vulnerable to clinical factors.Introduction

Infants with Congenital Heart Disease, particularly those who undergo early corrective or palliative surgical procedures, are at increased risk of neurodevelopmental impairments (1,2), which may arise from impaired early brain development. We aimed to characterise how global and regional brain volumetric brain growth in the perioperative period in individual infants with CHD deviates from typical development, and assess the relationship with clinical risk factors.Methods

36 infants with a diagnosis of critical or severe CHD [19 male, median (Interquartile range IQR) gestational age at birth 38.5 (38.1-39.0) weeks] underwent pre- and postoperative brain MRI on a Philips Achieva 3-Tesla system situated on the neonatal unit at St Thomas’ Hospital London during natural sleep. Data were acquired with a dedicated 32-channel neonatal head coil and positioning system (3). T2-weighted multi-slice turbo spin echo scans were acquired in sagittal and axial planes (repetition time 12,000ms; echo time 156ms; flip angle 90°; slice thickness 1.6 mm; slice overlap=0.8 mm; in-plane resolution: 0.8x0.8mm). 3-D volumes were reconstructed using a dedicated algorithm to correct motion (4,5). Volumes were extracted for cortical grey matter, white matter, total deep grey matter, cerebellum, brainstem, ventricles and extracerebral cerebrospinal fluid and total tissue volume, using an automatic neonatal-specific segmentation algorithm (6,7).Normative curves of typical volumetric brain development were created using Gaussian Process Regression, a Bayesian non-parametric regression technique (https://sheffieldml.github.io/GPy/) using data acquired using the same MR acquisition protocol from a total of 219 healthy infants scanned after 37 weeks gestational age as part of the developing Human Connectome Project (dHCP) [median (IQR) age at birth = 40.1 (39.1–41) weeks; 109 male] as described in (8,9). Z-scores, representing the degree of positive or negative deviation from the normative mean for postmenstrual age at scan, days of life and sex, were calculated for each brain volume from each infant with CHD before and after surgery. The degree of change in these z-scores was correlated with clinical risk factors using partial spearman’s rank correlations.

Results

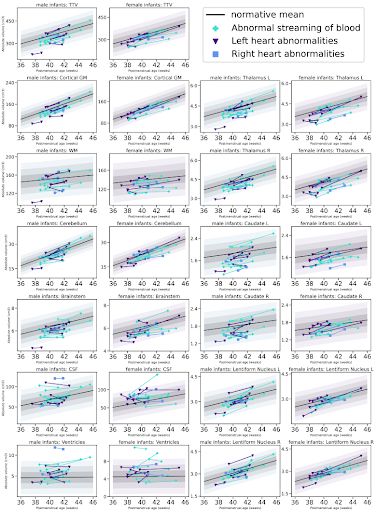

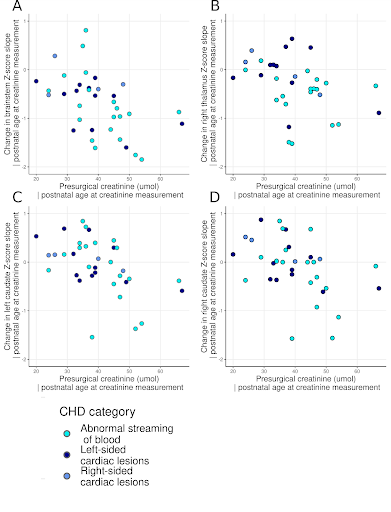

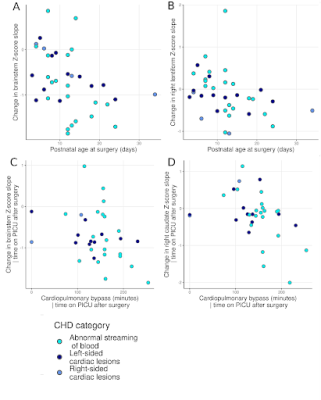

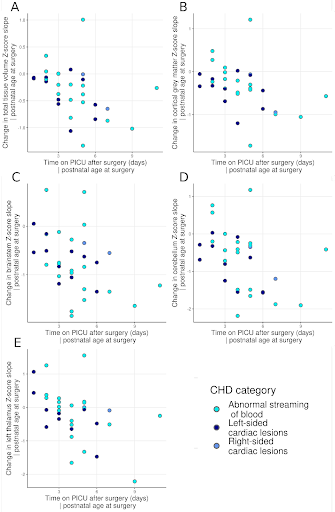

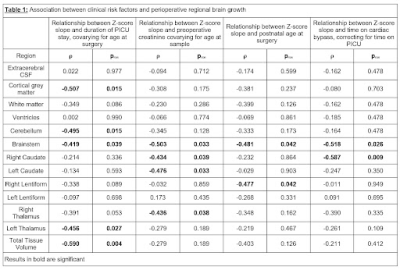

Perioperative growth was reduced in cortical grey matter, white matter, cerebellum, brainstem, right thalamus, right lentiform, total tissue volume and extracerebral CSF spaces (Figure 1). Higher preoperative serum creatinine levels were associated with impaired brainstem, caudate nuclei and right thalamus growth (all pFDR=0.033; Figure 2, Table 1). Older postnatal age at surgery was associated with impaired brain stem and right lentiform growth (both pFDR=0.042, Figure 3, Table 1). Longer cardiopulmonary bypass duration was associated with impaired brainstem and right caudate growth (pFDR<0.027; Figure 3, Table 1). Duration of postoperative intensive care stay was associated with the degree of impaired perioperative growth of total tissue volume, and cortical grey matter, brainstem, cerebellum and left thalamus volumes in particular (pFDR <0.05; Figure 4, Table 1).Discussion and Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first use of a normative modelling approach to assess perioperative brain development in infants with CHD in order to identify significant changes in individual brain growth trajectories. We demonstrate that Infants with CHD show an overall slowing of intracranial growth in the acute postoperative period.While group studies have reported larger differences in brain tissue volumes between infants with CHD and controls after surgery compared to before (10,11), our study highlights the heterogeneity of perioperative trajectories in infants with CHD.

Brainstem growth was particularly vulnerable to clinical course, with preoperative creatinine levels, later age at surgery, longer duration of cardiopulmonary bypass, and longer time on intensive care postoperatively associated with impaired growth in this region. Impaired growth in the right lentiform and right caudate nuclei was associated with later age at surgery and longer time on cardiopulmonary bypass respectively. The impaired growth of both these regions and their association with multiple clinical risk factors appears to reflect a particular vulnerability to acute and chronic hypoxic perioperative injury. Further research is needed to confirm whether postoperative extracardiac complications related to systemic hypoxia are specific risk factors for impaired brain growth in this population and whether alterations in brain growth identified in the acute postoperative period persist into later childhood and beyond.

Interestingly, higher preoperative serum creatinine levels, despite all being within the (laboratory specific) normal ranges, were associated with impaired growth in the brainstem and basal ganglia. As a readily available measure of renal function, serum creatinine may represent a potentially modifiable preoperative clinical biomarker in this population. Strategies to optimise renal function and minimise the risk of acute kidney injury perioperatively, such as strict avoidance of nephrotoxic medicines preoperatively, and close monitoring of fluid balance, may ameliorate impaired growth of the brainstem and the basal ganglia in infants with CHD, however this hypothesis requires further investigation.

Overall, these results provide opportunities to optimise perioperative brain growth in individual neonates with CHD.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the families who participated in this study. We also thank our research radiologists; our research radiographers, and our neonatal scanning team. In addition, we thank the staff from the St Thomas’ Hospital Neonatal Intensive Care Unit; the Evelina London Children’s Hospital Fetal and Paediatric Cardiology Departments; the Evelina London Paediatric Intensive Care Unit and the Centre for the Developing Brain at King’s College London.

Funding: This research was funded by the Medical Research Council UK (MR/L011530/1; MR/V002465/1), the British Heart Foundation (FS/15/ 55/31649) and Action Medical Research (GN2630). The normative sample was collected as part of the Developing Human Connectome Project, funded by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/20072013)/European Research Council grant agreement no. 319456. This research was supported by the Wellcome Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Centre for Medical Engineering at King's College London (WT 203148/Z/16/Z), Medical Research Council UK strategic grant (MR/K006355/1), Medical Research Council UK Centre grant (MR/N026063/1) and by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. LCG is supported by the Comunidad de Madrid-Spain (Support for R&D Projects; BGP18/ 00178). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

References

1. Latal B. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of the Child with Congenital Heart Disease. Clin. Perinatol. 2016;43:173–185 doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2015.11.012.

2. Peyvandi S, Latal B, Miller SP, McQuillen PS. The neonatal brain in critical congenital heart disease: Insights and future directions. NeuroImage 2019;185:776–782 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.045.

3. Hughes EJ, Winchman T, Padormo F, et al. A dedicated neonatal brain imaging system. Magn. Reson. Med. 2017;78:794–804 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26462.

4. Cordero-Grande L, Teixeira RPAG, Hughes EJ, Hutter J, Price AN, Hajnal JV. Sensitivity Encoding for Aligned Multishot Magnetic Resonance Reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 2016;2:266–280 doi: 10.1109/TCI.2016.2557069.

5. Cordero-Grande L, Hughes EJ, Hutter J, Price AN, Hajnal JV. Three-dimensional motion corrected sensitivity encoding reconstruction for multi-shot multi-slice MRI: Application to neonatal brain imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2018;79:1365–1376 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26796.

6. Makropoulos A, Aljabar P, Wright R, et al. Regional growth and atlasing of the developing human brain. Neuroimage 2016;125:456–478 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.047.

7. Makropoulos A, Robinson EC, Schuh A, et al. The developing human connectome project: A minimal processing pipeline for neonatal cortical surface reconstruction. NeuroImage 2018;173:88–112 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.01.054.

8. Bonthrone AF, Dimitrova R, Chew A, et al. Individualized brain development and cognitive outcome in infants with congenital heart disease. Brain Commun. 2021;3 doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcab046.

9. Dimitrova R, Arulkumaran S, Carney O, et al. Phenotyping the Preterm Brain: Characterizing Individual Deviations From Normative Volumetric Development in Two Large Infant Cohorts. Cereb. Cortex N. Y. N 1991 2021;31:3665–3677 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhab039.

10. Meuwly E, Feldmann M, Knirsch W, et al. Postoperative brain volumes are associated with one-year neurodevelopmental outcome in children with severe congenital heart disease. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:10885 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47328-9.

11. Ortinau CM, Mangin-Heimos K, Moen J, et al. Prenatal to postnatal trajectory of brain growth in complex congenital heart disease. NeuroImage Clin. 2018;20:913–922 doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.09.029.

Figures