2526

Clinical Utility of Optimised Ultra-Low Field Structural MR Brain imaging in Neonates1Centre for the Developing Brain, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Evelina Children's hospital, London, United Kingdom, 3MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 4Hyperfine, Inc., Connecticut, CT, United States, 5Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Evelina Children’s Hospital, London, United Kingdom, 6Centre for Neuroimaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Neuro, Low-Field MRI

Perinatal brain injury and congenital brain abnormalities are common. Access to definitive neuro imaging is limited globally, particularly within resource constrained settings, or in infants too sick to transfer to scanning departments. New devices utilising ultra-low field magnets may herald a revolution in lower-cost high-access MRI, but preliminary results using manufacturer standard adult-optimised sequences has produced suboptimal image quality in neonates. We performed optimisation of low field MRI pulse sequence design and demonstrate enhanced visualization of key brain tissues and neuroanatomical structures. Neonatal-specific sequences show promising performance across a range of gestational maturities and perinatal brain abnormalities.Introduction

Newborn infants are at risk of congenital or acquired brain abnormalities for which Magnetic Resonance (MR) imaging is often critical for diagnosis and management, and superior to cranial ultrasound.1–3 Current imaging typically utilises 1.5 Tesla (T) or 3T MR scanners, which require significant infrastructure and economic investment to both install and maintain.4 Consequently, there is substantial inequity of access to MR technology globally, with infant access to neuroimaging extremely limited or non-existent in low resource countries5. Within high-resource settings, the need to transport infants away from the Intensive Care Unit to radiology departments may preclude MR scanning for the sickest infants for whom transport is too high risk, but for which imaging may be most valuable.Ultra-low Field (ULF) technology could potentially provide innovative solutions for these challenges and thus improve clinical care for substantial numbers of infants globally.4,6 However, sequences in mainstream use across adult ULF imaging have been shown to be inadequate when used to image the neonatal brain, providing insufficient detail for clinical utilisation.7–9

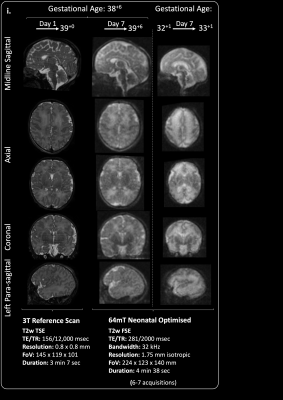

We have previously demonstrated optimisation of ULF structural MR sequences for the developing brain10 and now demonstrate exemplar neonatal ULF MR imaging sets using dedicated neonatal optimised acquisitions.

Methods

Healthy and clinically referred neonates were recruited from Evelina Children’s Hospital as part of two NHS UK REC approved studies (12/LO/1247, 19/LO/1384). Infants referred for clinical scans received chloral hydrate sedation as standard, healthy control participants were scanned in natural sleep. All medical support requirements, such as ventilation, intra-venous infusions or thermoregulation were continued throughout scanning.Paired MR brain scans were acquired using the 64 mT Hyperfine MR scanner scanner (hardware version 1.7; software versions 8.2.0 & 8.5.2) and a reference standard Philips Achieva 3T MR scanner for all infants. T1w MPRAGE, and T2w turbo spin echo sequences were acquired on the 3T scanner using neonatal optimised acquisition sequences 11.

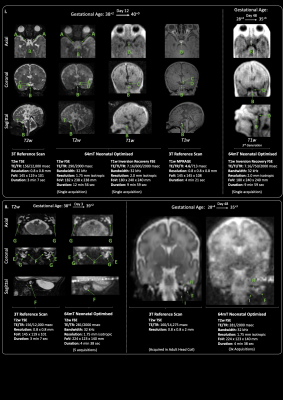

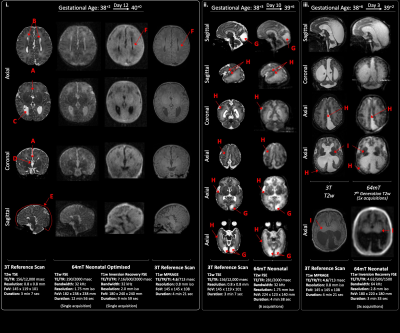

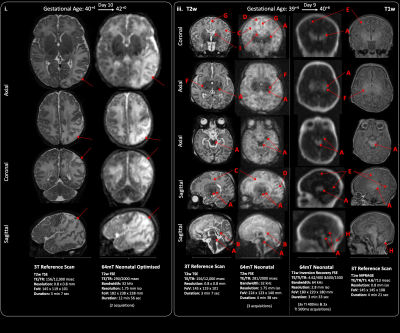

Specific sequence parameters are presented in the accompanying figures. We enhanced signal to noise ratio by repeated sequence acquisition and mean signal averaging. Inter-acquisition motion correction was achieved through rigid registration using FSL FLIRT (FMRIB, Oxford, UK). Where relevant, the number of acquisitions averaged are listed within all figures.

Results

We performed 102 paired ULF and 3T scans in 87 infants. Median gestational age at birth was 38+2 weeks (range 25+3-42+1), and median postmenstrual age at scan 40+2 weeks (31+3-53+4). Two ULF scans were abandoned at start of scanning due to the infants waking – (100/102 [98%] success on first scan attempt); both abandoned scans were subsequently successful on second attempt.67 scans were carried out because of risk/suspicion of cerebral abnormality, and 35 scans were performed in healthy controls. Infants had a range of intensive care requirements including invasive ventilation and multiple infusions. All scans were well tolerated with no adverse events. ULF sequences successfully demonstrated contrasted CSF, white and grey matter, and identified key structures such as the corpus callosum, gyral folding, pituitary tissue, optic chiasm, inner ear and posterior limb of the internal capsule. Optimised neuroanatomical imaging are shown in Figure 1 and 2; clear maturational differences can be determined between the normally formed term and preterm brains. Inner ear definition of the semi-circular canals, cochlear, and vestibule is achievable, as is delineation of the course of the vestibulocochlear nerve prior to its bifurcation.

ULF structural definition was sufficient to distinguish the normally developed brain from infants with abnormal or disrupted brain development. Such examples of congenital brain dysgenesis are shown in figure 3. Key clinical information, which may suggest aetiology and prognosis, such as cystic change, patterns of abnormal cortical organisation and gyral folding, ventricular dilatation, and areas of brain hypoplasia are identifiable.

Examples of acquired injury are included in figure 4; ULF sequences were able to identify haemorrhage, cystic injury, white matter loss and patterns of abnormal T1 and T2 signal in white and grey matter -consistent with infarction and hypoxia-ischaemia, in corroboration with 3T appearances.

Non-identified pathologies on ULF tended to be small discreet lesions such as punctate white matter lesions, striation and microcysts, which are of uncertain prognostic importance.

Discussion

Neonatal ULF sequences can differentiate the normally developed brain from brain dysgenesis, as well as identify patterns of acquired injury. The ability to distinguish underlying pathology is critical in the diagnosis of infants presenting with neurological abnormality; clinical examination alone may be unable to determine between a wide range of aetiologie, each potentially requiring different management.Application of ULF MR, through commercially available or open-source domains, could thus be transformative; MR scanner access could reach areas of the globe for which there is currently no provision. Furthermore, infants undergoing intensive care, too sick to transport, might profit from pathology or time-critical treatment defining imaging at their cotside. Scanning during ongoing neonatal intensive care was both feasible and safe with MR precautions.

Further investigation is now required to establish diagnostic thresholds of ULF scanning, through blinded comparative radiological reporting and comparison with Cranial ultrosongraphy.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Ultralow field Neuroimaging In The Young: INV-005798), the MRC (Translation Support Award: MR/V036874/1), the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering [WT 203148/Z/16/Z], and the Medical Research Council Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders [MR/N026063/1].References

1. Arulkumaran S, Tusor N, Chew A, Falconer S, Kennea N, Nongena P, et al. MRI Findings at Term-Corrected Age and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in a Large Cohort of Very Preterm Infants. Am J Neuroradiol [Internet]. 2020 Aug;41(8):1509–16. Available from: http://www.ajnr.org/lookup/doi/10.3174/ajnr.A6666

2. Shankaran S, McDonald SA, Laptook AR, Hintz SR, Barnes PD, Das A, et al. Neonatal Magnetic Resonance Imaging Pattern of Brain Injury as a Biomarker of Childhood Outcomes following a Trial of Hypothermia for Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. J Pediatr [Internet]. 2015 Nov;167(5):987-993.e3. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022347615008690

3. Rutherford MA, Pennock JM, Dubowitz LMS. CRANIAL ULTRASOUND AND MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING IN HYPOXIC-ISCHAEMIC ENCEPHALOPATHY: A COMPARISON WITH OUTCOME. Dev Med Child Neurol [Internet]. 2008 Nov 12;36(9):813–25. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-8749.1994.tb08191.x

4. Sarracanie M, Lapierre CD, Salameh N, Waddington DEJ, Witzel T, Rosen MS. Low-Cost High-Performance MRI. Nat Publ Gr. 2015;1–9.

5. International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). No Title [Internet]. Available from: https://humanhealth.iaea.org/HHW/DBStatistics/IMAGINEMaps3.html

6. Lee AC, Kozuki N, Blencowe H, Vos T, Bahalim A, Darmstadt GL, et al. Intrapartum-related neonatal encephalopathy incidence and impairment at regional and global levels for 2010 with trends from 1990. Pediatr Res [Internet]. 2013 Dec 20;74(S1):50–72. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/pr2013206

7. Sien ME, Robinson AL, Hu HH, Nitkin CR, Hall AS, Files MG, et al. Feasibility of and experience using a portable MRI scanner in the neonatal intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child - Fetal Neonatal Ed [Internet]. 2022 Jul 4;fetalneonatal-2022-324200. Available from: https://fn.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/archdischild-2022-324200

8. Padormo F, Cawley PA. Ultralow Field T1 Mapping. Magn Reson Med.

9. Cawley P, Padormo F, Consortium U, Dillon L, Hughes E, Maggioni A, et al. Portable Point-Of-Care Ultra-Low Field Magnetic Resonance Brain Imaging for Newborn Infants. Neonatal Soc Autumn Meet R Soc Med London. 2021;

10. Cawley P, Padormo F, Consortium U, Dillon L, Hughes E, Almalbis J, et al. Optimisation of Structural MR Imaging Sequences in a Neonatal Cohort at 64 mT. In: ISMRM 2022, London UK. 2022. p. Abstract #0737.

11. Hughes EJ, Winchman T, Padormo F, Teixeira R, Wurie J, Sharma M, et al. A dedicated neonatal brain imaging system. Magn Reson Med [Internet]. 2017 Aug;78(2):794–804. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mrm.26462

Figures

Figure 4. Acquired injuries. i. White matter & cortical parieto-occipital infarction (red arrows). ii. Basal ganglia, thalamic, corticospinal tract

& mesencephalon injury secondary to perinatal Hypoxia-ischaemia. A Deep grey matter, hippocampal, cerebral peduncle & brainstem injury shown as abnormal low T2 or high T1 signal, B abnormal high T2 signal in the corpus callosum, C abnormal high T2 signal in the white matter, D sub-cortical white matter highlighting, E cortical highlighting, F Abnormal PLIC signal, G widened interhemispheric fissure, H subdural haemorrhage