2516

Mechanical Properties of Pediatric Central Nervous System Tumors in Children With and Without Neurofibromatosis Type 11University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States, 2Neuroradiology, Nemours Children's Health, Wilmington, DE, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neuro, Tumor

Pediatric brain tumors have developmental consequences even when prognoses are favorable. Mechanical characterization using magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) has previously revealed adult gliomas are softer than brain tissue. However, pediatric tumors are known to differ behaviorally and cytoarchitecturally from adult tumors. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) imparts genetic predisposition to gliomas, but also results in spongiform regions in white matter tissue. Here we use MRE for the first time in NF1 and in pediatric low-grade gliomas and we find that pediatric gliomas are softer than reference tissue, while spongiforms are stiffer.Introduction

Brain and central nervous system (CNS) tumors are the most common cause of cancer-related mortality in the pediatric population, with gliomas being the most common CNS tumors. Prognoses for pediatric tumors are suboptimal, as even in low-grade tumors, management techniques including surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiation lead to tissue damage in the developing brain1. Therefore, in the developing brain, best-practices for management of less threatening tumors, such as low-grade gliomas, must be weighted to consider a patient’s holistic health and development. Gliomas can originate from one of several progenitor cells, are staged by severity, and have a range of manifestations2. While most gliomas have no known cause, approximately 20% of pediatric gliomas occur in individuals with genetic predispositions for glioma development3. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), for example, is an autosomal dominant condition resulting in varied CNS manifestations including optic pathway gliomas and spongiform white matter changes4. Spongiforms (also called focal abnormal signal intensities, FASIs4) are non-neoplastic lesions which tend to increase in number and size until age 12 and they are often accompanied by vacuolating alterations of the myelin structure5.Adult gliomas have previously been characterized in vivo by their mechanical properties using magnetic resonance elastography (MRE)6, but these studies have mostly been conducted in high grade gliomas, and not in children nor in individuals with genetic predispositions7. Pediatric tumors differ cytoarchitecturally and behaviorally from adult tumors – e.g., pediatric low-grade gliomas uniquely almost never show malignant progression3. The purpose of this work is to characterize low-grade pediatric gliomas and utilize mechanical properties as a tool to investigate CNS neoplasms in NF1. Being able to noninvasively measure tumor mechanical properties can aid in prediction of tumor grade, malignancy, and proliferation, which could improve management and outcomes in these patients.

Methods

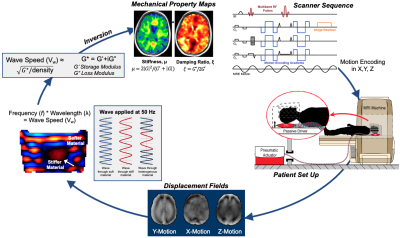

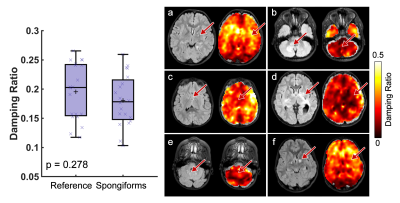

Twenty-four pediatric subjects (age: 3-18 years) with a confirmed diagnosis of either NF1 or a primary low-grade glioma (WHO Grade I or II) of at least 12 mm were enrolled in our study. 14 subjects were classified as primary glioma, with 4 of these subjects having more than one glioma, for a total of 18 primary gliomas. 8 additional subjects had a diagnosis of NF1, each with spongiform white matter changes of various sizes and locations, and 6 had a classic optic nerve glioma. All subjects were scanned on a GE Signa 3T PET/MR scanner (GE Healthcare; Waukesha, WI). MRE scans were acquired using an EPI sequence at 2.5 mm isotropic resolution, with FOV of 240 x 240 mm2, matrix size 96 x 96, 48 slices, and TR/TE of 7200/88 ms. 50 Hz vibrations were delivered to the head by a pneumatic actuator system and pillow driver (Resoundant; Rochester, MN). The MRE imaging time was 3 min 15 sec. MRE displacement data was processed through a nonlinear inversion algorithm (NLI)8 to solve for the complex shear modulus, G=G’+iG’’, which was converted to viscoelastic shear stiffness, μ=2|G|2/(G’+|G|), and damping ratio, =G’’/2G’ (Figure 1). Additionally, several anatomical scans were collected for tumor segmentation including a T2-weighted scan and a T2-FLAIR. Regions of interest were traced manually by a pediatric neuroradiologist. When spongiform changes were small and clustered closer than 4 mm, the region of interest was drawn around the entire area. Reference tissue for each subject was chosen as the average of all normal appearing white matter which was further than 12 mm away from the tumor boundary. Paired t-tests were used to calculate differences between tumor and reference tissue.Results

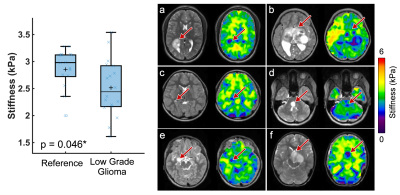

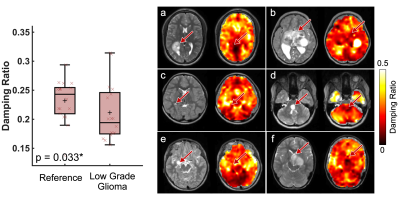

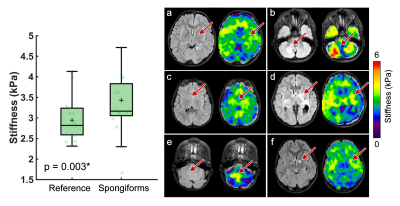

Pediatric low-grade gliomas were found to be 11.5% softer on average than normal appearing reference tissue (p=0.046; Figure 2) and had 11.4% lower damping ratio (p=0.033; Figure 3). Interestingly, in people with NF1 we found that spongiform regions were stiffer than reference tissue by an average of 16.4% (p=0.003; Figure 4), though spongiforms showed no significant difference in damping ratio (p = 0.278; Figure 5). Degree of stiffness or damping ratio difference did not appear to correlate with lesion size.Discussion and Conclusion

Pediatric gliomas have differing mechanical properties than their surrounding tissue, such that gliomas are less stiff and have a lower damping ratio as compared to reference tissue, which agrees with research in adult high-grade gliomas9,10. In adult work, glioblastomas (a more aggressive tumor) have been reported to be 16.5% softer on average than the normal appearing reference tissue7. Due to differing cellular phenotypes and disease progression, separate assessment of pediatric gliomas from adult gliomas is critical towards informing the differing management strategies used in the developing and mature brain. Further, in pediatrics, it can be challenging to assess tumor malignancy using a traditional Ki-67 immunostaining, as the developing CNS has a naturally robust proliferative potential, and novel neuroimaging metrics can aid in comprehensive tumor evaluations3. It remains unknown exactly why spongiform regions are stiffer than surrounding tissue, but the increased size and number of myelin vacuoles in these areas may have biomechanical effects and warrants further investigation. To our knowledge this is the first time that tumor mechanical properties have been assessed in vivo pre-surgery using MRE in the pediatric brain.Acknowledgements

Delaware INBRE (P20-GM103446) and Delaware CTR ACCEL (U54-GM104941)References

1. Armstrong GT, Conklin HM, Huang S, et al. Survival and long-term health and cognitive outcomes after low-grade glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13(2):223-234. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noq178

2. Louis DN, Holland EC, Cairncross JG. Glioma classification: A molecular reappraisal. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(3):779-786. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61750-6

3. Sturm D, Pfister SM, Jones DTW. Pediatric gliomas: Current concepts on diagnosis, biology, and clinical management. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(21):2370-2377. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.73.0242

4. Russo C, Russo C, Cascone D, et al. Non-Oncological Neuroradiological Manifestations in NF1 and Their Clinical Implications. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(1831):1-20.

5. Razek AAKA. MR imaging of neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions of the brain and spine in neurofibromatosis type I. Neurol Sci. 2018;39(5):821-827. doi:10.1007/s10072-018-3284-7

6. Hiscox L V, Johnson CL, Barnhill E, et al. Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) of the human brain : technique , findings and clinical applications. Phys Med Biol. 2016;61:R401-R437. doi:10.1088/0031-9155/61/24/R401

7. Bunevicius A, Schregel K, Sinkus R, Golby A, Patz S. REVIEW: MR elastography of brain tumors. NeuroImage Clin. 2020;25(November 2019):102109. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102109

8. McGarry MDJ, Van Houten EEW, Johnson CL, et al. Multiresolution MR elastography using nonlinear inversion. Med Phys. 2012;39(10):6388-6396. doi:10.1118/1.4754649

9. Murphy MC, Huston III J, Ehman RL, Huston J, Ehman RL. MR elastography of the brain and its application in neurological diseases. Neuroimage. 2019;187(August 2017):176-183. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.10.008

10. Simon M, Guo J, Papazoglou S, et al. Non-invasive characterization of intracranial tumors by magnetic resonance elastography. New J Phys. 2013;15(8):085024. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/15/8/085024

Figures