2513

Association of socio-economic status and perceived parental stress effects with infant cortical development1Department of Radiology, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, United States, 2Department of Radiology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States, 3Department of Biomedical Engineering, School of Engineering and Applied Science, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Normal development, Gray Matter

Environmental factors such as socio-economic status (SES) and parental stress have significant impacts on cognitive performance, but their links to brain development during infancy are not known. We collected high-resolution structural MRI, SES and perceived stress scales (PSS) of 70 infants and their caregivers aged 0-20 months to investigate the association of these environmental factors and brain development. The total brain, gray matter, and white matter volumes all increase rapidly with age. Higher SES is significantly correlated with greater cortical volume, particularly in the right hemisphere. Lower PSS tends to be associated with higher cortical volume, though not significantly.Introduction

Infant brain development is characterized with probably the most dynamic and rapid structural and functional changes across the lifespan1. Human brain gray matter volume increases most dramatically during the first 2 years of life2, a typical period of acquisition of motor skills and other important developmental milestones. Literature has suggested that environmental risk factors have a significant impact on brain maturation3,4. For example, parental stress and family socioeconomic status (SES) have demonstrated lasting effects on brain structural development in childhood and even adulthood5,6. Previous studies have shown positive associations between SES and brain volume in children7 and young adults8. However, little is known about the interactions between brain development and environmental factors in infancy. We hypothesized that the brain structural changes during infancy can be affected by environmental factors like SES and parental stress. Here, we measured the brain gray and white matter volumes in 70 infants using structural MRI and assessed their parental stress and SES through parental questionnaires. The goal of the study is to investigate the association between brain structural development and environmental factors in typical developing infants from 0 to 20 months.Methods

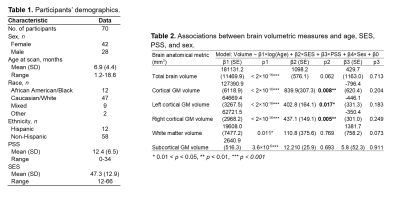

Participants and data acquisition: 70 typically developing infants (42F/28M) aged 0 to 20 months were included in this study and scanned on a 3.0T Siemens Prisma scanner. T1-weighted images (T1w) were acquired using MPRAGE sequence with a voxel size of 0.8mm isotropic. The T1w parameters were: TR/TE/TI = 2400/2.24/1060ms, FOV= 256 × 240 mm2, acquisition matrix = 320 x 300, and 0.8 mm slice thickness. The acquisition time of the T1w was 6.38 min. Parental questionnaires: Parents of the infants completed questionnaires about socioeconomic status (SES) and the perceived stress scale (PSS). The SES score was derived from two values – parental education and occupation. SES was quantified using the Amherst modification of the Hollingshead two-factor index9. PSS is a 10-item questionnaire developed to capture the caregiver’s perception of their life as unpredictable, uncontrollable, or overloading in the last month. Answer choices range from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). To score total stress, answer choices are summed after reverse scoring questions 4, 5, 7, and 8. Individual scores ranged from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher perceived stress10. Data analysis: All infants’ T1w images were segmentation using the Infant FreeSurfer11. Based on the segmentation, the total brain, cortical and subcortical gray matter (GM), and white matter (WM) volumes were then measured. Statistical analyses were performed to examine the associations of the above brain volumetric measures with age, SES, PSS, and sex by fitting below logarithmic models using R software:Volume (i.e., volumetric measure) ~ β1 log(Age) + β2 SES + β3 PSS + β4 Sex + β0

Results

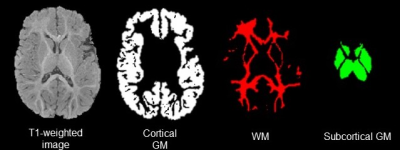

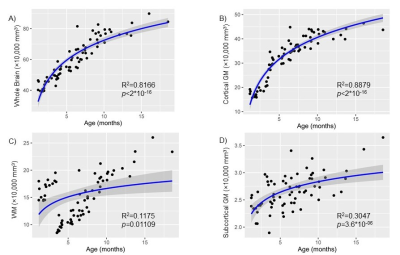

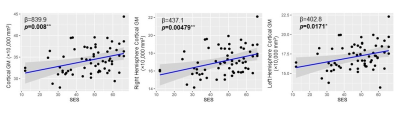

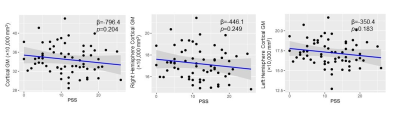

Figure 1 illustrates the brain segmentation of T1w images into cortical and subcortical GM and WM regions from a representative infant at 10 months of age. To better fit the developmental changes of brain volumetric measures, logarithmic models were used. We found a strong positive association between age and total brain volume (β1 = 181131.2, p < 0.001), cortical GM volume (β1 = 127390.9, p < 0.001), left cortical GM volume (β1 = 64669.4, p < 0.001), right cortical GM volume (β1 = 62721.5, p < 0.001), subcortical GM volume (β1 = 2640.9, p < 0.0001) and WM volume (β1 = 19608.0, p < 0.05) (Figure 2 and Table 2). Interestingly, SES showed significant, positive associations with cortical GM volume (β2 = 839.9, p = 0.008; Figure 3), especially in the right hemisphere (β2 = 437.1, p = 0.005). While whole brain volume, subcortical GM volume, and WM volume had no significant correlation with SES. In addition, we found that there was a weak negative correlation between cortical GM volume and parental stress (β3 <0; Figure 4), though it was not significant.Discussion

In this study, we explored the relationship between brain structural development and environmental factors (i.e., SES, parental stress) in infancy. Consistent with previous literature1,2, the whole brain volume as well as GM and WM volumes increase rapidly with age during this early developmental period. SES showed strong impact on cortical GM development, but not WM development. Higher SES is significantly associated with greater cortical volume, particularly in the right hemisphere. Although we didn’t observe significant correlation, lower perceived parental stress tends to be associated with higher cortical volume. Our findings demonstrated that environmental factors such as parental stress and family socio-economic status can influence brain structural development as early as and throughout infancy. The examined relationship provides insight into the significant impact of environmental effects on brain development, especially during the critical and vulnerable period of infancy. The analysis of the relationship between environmental factors and infant’s neurodevelopmental outcomes (e.g., cognitive, language or motor skills) is under way. Potential correlations of environmental factors with cortical volumes at gyral level or subcortical volumes will be further investigated.Acknowledgements

This study is funded by NIH R01MH092535, R01MH125333, R01EB031284, R01MH129981, R21MH123930 and P50HD105354.References

1. Ouyang M, Duboi J, et al. Delineation of early brain development from fetuses to infants with diffusion MRI and beyond. NeuroImage. 2019; 185: 836-850.

2. Bethlehem R, Seidlitz J, et al. Brain charts for the human lifespan. Nature. 2022; 604: 525-533.

3. Jednorog K, Altarelli I, et al. The influence of socioeconomic status on children’s brain structure. PLoS ONE. 2012; 7(8).

4. Talge M, Neal C, et al. Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: how and why? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007; 48(3): 245-261.

5. Tooley U, Bassett D, Mackey A. Environmental influences on the pace of brain development. Nature Neurosci Rev. 2021; 22: 372-384.

6. Mackes N.K, Golm D, et al. Early childhood deprivation is associated with alterations in adult brain structure despite subsequent environmental enrichment. PNAS. 2020; 114(1): 641-649.

7. Yang J, Liu H, et al. Regional gray matter volume mediates the relationship between family socioeconomic status and depression-related train in a young healthy sample. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2016; 16: 51-62.

8. McDermott C, Seidlitz J. et al. Longitudinally mapping childhood socioeconomic status associations with cortical and subcortical morphology. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2019; 39(8): 1365-1373.

9. Hollingshead AB. Two factor index of social position. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1957.

10. Cohen S, Kamarck T, & Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983; 24(4): 385-396.

11. Zöllei L, Iglesias J.E, Ou Y, Grant P.E & Fischl B, 2020. Infant FreeSurfer: An automated segmentation and surface extraction pipeline for T1-weighted neuroimaging data of infants 0–2 years. Neuroimage. 2020; 218: 116946.

Figures

Table 1. Participants’ demographics.

Table 2. Associations between brain volumetric measures and age, SES, PSS, and sex.