2410

GPU-accelerated JEMRIS for extensive MRI simulations.1Biomedical Physics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, School of Medicine, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany, 3Altair Engineering GmbH, Boeblingen, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Simulations, Software Tools

Bloch simulations is a powerful tool in MRI research and education as it allows predicting the signal evolutions in magnetic resonance experiments for various applications. However, Bloch simulations require solving ordinary differential equations for the whole spin ensemble and can thus become infeasible for realistic scenarios with large total number of spins. Therefore, the present work investigates the potential of a GPU-based implementation for accelerated Bloch simulations as an extension to the open source Juelich Extensible MRI Simulator (JEMRIS) in comparison to the existing MPI CPU implementation.

Introduction / Purpose:

Bloch simulations can be used to numerically solve phenomenological differential equations for a given spin system in an external magnetic field and thus enable valuable insights into MR experiments. Moreover, Bloch simulations allow the precise description of dynamic effects but can be computationally expensive for large spin systems. Our previous work demonstrated the utility of Bloch simulations using JEMRIS for the investigation of spin history effects induced by motion [1]. JEMRIS currently relies on sequential and parallel CPU computations [2], while other GPU-based frameworks are either not open-source or are lacking generalizability [3,4,5]. The purpose of the present work was to extend the open-source general-purpose framework JEMRIS with GPU support for accelerated flexible computation of large spin systems, such as the investigation of off-resonance, gradient spoiling, or diffusion effects.Methods:

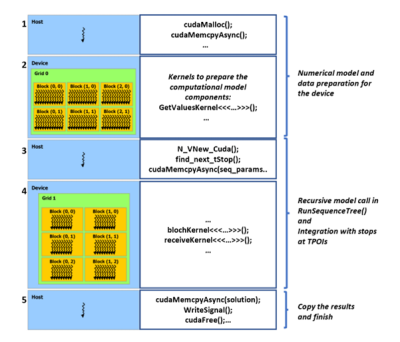

ImplementationThe GPU extension for JEMRIS was developed in CUDA C++ [6] maintaining the original object-oriented implementation with code encapsulation. While keeping the numerical solver library SUNDIALS [7], the later version 5.7 was used to enable GPU-accelerated time integration [8]. Conceptually, the main changes in JEMRIS for the GPU support are: World, Sample, Coil, and Model classes were altered to allocate the GPU memory and copy the data of the computational core to the device; further Model communicates with the sequence tree and calls the solver on GPU at the timepoints of interest (TPOI). Bloch_CV_Model implements the numerical CVode model for solving the equations for all spins in parallel on GPU eliminating the serial loop in the original CPU implementation, and Coil performs signal reception as a reduction using the CUB [9] library. Figure 1 conceptually highlights the described changes.

The GPU implementation was optimized as follows: a) memory initialization only during start-up, b) minimized and asynchronous host-device and device-host data transfers, as well as asynchronous kernel launches, and c) optional single precision arithmetic. The aim of the first two steps was to optimize GPU usage. Since many GPU models exhibit limited double precision arithmetic performance compared to single precision, GPU-JEMRIS was implemented to include model carrying floats by converting some data from double to single precision.

Simulation

Simulations were carried out on a workstation with 2xIntel Xeon Gold 6252 (24x2.10GHz) CPUs and NVIDIA Titan RTX (24GiB) GPU. The performance of a single CPU socket was compared to that of a single GPU device.

A chemical shift phantom experiment was carried out as follows: an EPI acquisition with a numerical brain phantom containing fat tissue and uniform transmission and reception from [2] was reproduced.

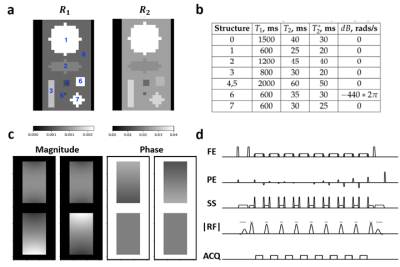

For the acceleration and accuracy benchmarking, a geometrical numerical phantom with assigned MR properties (Figure 2a,b) was simulated for a T1-weighted 2x undersampled 2D multi-shot TSE sequence (Figure 2d) converted from a clinical 3T Elition scanner (Philips Healthcare, The Netherlands). A 4-channel receiver coil array was simulated using Sigpy v0.1.23 (Figure 2c) [10]. JEMRIS simulates 1 spin per grid voxel, therefore, the number of spins in our experiments was increased by decreasing the through-plane resolution.

Results:

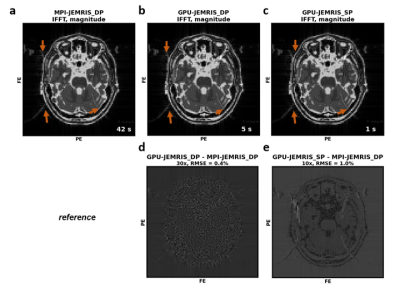

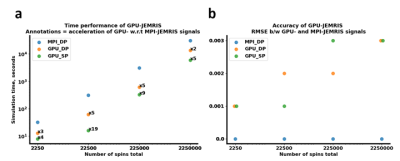

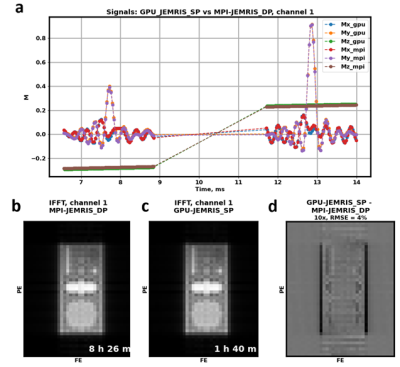

Figure 3 shows that the chemical shift artifacts appearing on the EPI simulations are similar for both GPU (Figure 3b,c) and CPU (Figure 3a) simulations, whereas the signal RMSE values are 2.4e-5 and 9.5e-5 for the double and single precision GPU compared to the double precision MPI simulators, respectively. Reconstructed images indicate negligible deviations for the double precision GPU simulations (Figure 3d), while the single precision GPU simulations also do not lose brain or artifact features (Figure 3c,e). The computational time decreases from 42 seconds with the MPI to 5 and 1 seconds with the double and single precision GPU simulations.Figure 4 summarizes the accuracy and performance results for double and single precision GPU simulations compared to MPI for the geometrical phantom with an increasing number of spins. While the MPI simulation time linearly scales up with the total number of spins, the simulation time curves for both double and single precision GPU simulations exhibit acceleration factors or x2-5 and x4-19, respectively (Figure 4a). The ratio of the double and single precision computational times on GPU is roughly x2-3. Regarding accuracy, the k-space RMSE between the GPU and MPI results are 0.1-0.3, being higher for the single precision computations and increasing with the number of spins (Figure 4b).

The echo signals (Figure 5a) and reconstructed images (Figure 5b) corresponding to the first channel from single precision GPU simulations and double precision MPI simulations for the 2.25 million spins case are in high agreement. While the k-space signal RMSE is 0.3, the image RMSE is 4%, which is expressed in slight differences at the edges of the phantom.

Discussion & Conclusion:

The proposed GPU-accelerated extension for JEMRIS demonstrated speed-ups of x2-5 and x4-19 using double and single precision solvers, respectively. All experiments showed k-space RMSE below 0.3 when compared to the MPI reference. The actual gain in performance depends on the problem size and correlates with the number of simulated spins. It is anticipated that GPU-accelerated Bloch simulations will enable further insights into more realistic large spin pool problems including experiments with large FOVs, multiple species, and motion effects.The code will be made available under https://github.com/BMRRgroup/jemris.

Acknowledgements

The present work was supported by DAAD (Project number: 57514573). The authors acknowledge research support from Philips Healthcare. The authors would like to thank Tom Geraedts for sharing his experience and code for the conversion of MR scanner sequences to JEMRIS sequence definition files with us.

References

1. Nurdinova, A., Ruschke, S., Karampinos, D. (2021). On the limits of model-based reconstruction for retrospective motion correction in the presence of spin history effects. ISMRM 2022.

2. Stöcker, T., Vahedipour, K., Pflugfelder, D., Shah, N. J. (2010). High-performance computing MRI simulations. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 64(1), 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.22406. Project website: https://www.jemris.org/

3. Liu, F., Velikina, J. v., Block, W. F., Kijowski, R., & Samsonov, A. A. (2017). Fast Realistic MRI Simulations Based on Generalized Multi-Pool Exchange Tissue Model. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 36(2), 527–537. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2016.2620961

4. Kose, R., & Kose, K. (2017). BlochSolver: A GPU-optimized fast 3D MRI simulator for experimentally compatible pulse sequences. Journal of Magnetic Resonance, 281, 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2017.05.007

5. Xanthis, C. G., Venetis, I. E., & Aletras, A. H. (2014). High-performance MRI simulations of motion on multi-GPU systems. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429X-16-48

6. NVIDIA corporation. CUDA toolkit documentation, https://docs.nvidia.com/cuda/index.html

7. Hindmarsh, A. C., Brown, P. N., Grant, K. E., Lee, S. L., Serban, R., Shumaker, D. E., & Woodward, C. S. (2005). SUNDIALS: Suite of nonlinear and differential/algebraic equation solvers. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software (TOMS), 31(3), 363–396. doi:10.1145/1089014.1089020

8. Balos, C. J., Gardner, D. J., Woodward, C. S., & Reynolds, D. R. (2021). Enabling GPU accelerated computing in the SUNDIALS time integration library. Parallel Computing, 108, 102836. doi:10.1016/j.parco.2021.102836

9. Merrill, D., NVIDIA corporation. (2022) CUB. https://nvlabs.github.io/cub/

10. SigPy: Python package for signal processing, with emphasis on iterative methods. https://sigpy.readthedocs.io/

Figures