2402

Open-source dynamic MRI workflow for reproducible research1Ming Hsieh Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Software Tools, Data Acquisition

This work presents an open-source workflow for dynamic MR acquisition and reconstruction. The entire workflow consists of vendor-agnostic tools to allow for immediate sharing of data, pulse sequence, and reconstruction code across sites. This work is an adaptation of Open-Source MR Imaging and Reconstruction Workflow to dynamic imaging (Veldmann et. al, MRM 88(6):2395-2407). Using the FIRE interface, we demonstrate a Gadgetron loader of acquisition metadata including k-space trajectories and present a pipeline to convert pulse sequences developed through HeartVista’s SpinBench into Pulseq for easy sharing of sequences.Introduction

We demonstrate an open-source workflow for interactive real-time MRI (RT-MRI) with online image reconstruction. Many RT-MRI applications require low-latency reconstruction (e.g., interventional guidance or closed-loop feedback). This work is motivated by the fact that MRI research is split across many vendors, and open-source vendor-agnostic tools exist to allow for sharing between all platforms [1], [2]. We demonstrate three examples: spiral gradient-echo (GRE) and spiral balanced steady-state-free-precession (bSSFP) speech production imaging [3], and spiral bSSFP cardiac imaging.Methods

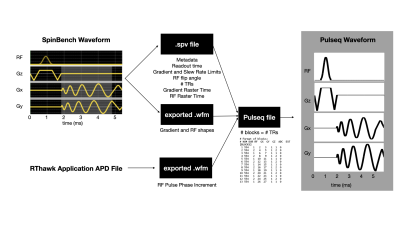

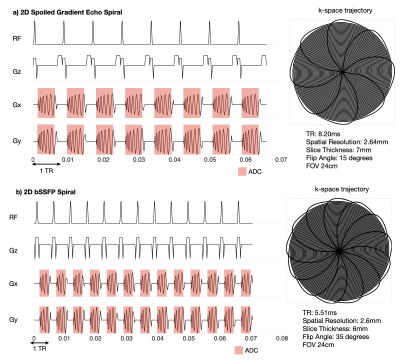

Pulse sequences were developed using SpinBench (HeartVista, Inc, Menlo Park, CA), an intuitive pulse sequence development tool designed for use with the RTHawk (HeartVista, Inc, Menlo Park, CA) real-time imaging console [4]. These pulse sequences are not easily sharable, so they were converted to Pulseq [5]. SpinBench files are parsed for metadata including readout time, hardware limits, flip angle, and raster times. SpinBench exported waveforms are imported into Pulseq directly. For each TR, the convertor creates one Pulseq block with RF, Gx, Gy, and Gz all active and with the appropriate delays and truncation to match the original SpinBench specification. Figure 1 illustrates this in detail.Pulseq files do not share arbitrary k-space metadata (e.g., acquisition labels and k-space trajectories). Therefore, this data must be stored separately in a separate metadata file and sent to the server prior to scanning. Python or MATLAB MRD servers have been used to parse the new trajectory [1]. In this work, a similar MATLAB server is used with slight modifications to support dynamic imaging. Specifically, we store a cache of k-space data during new acquisitions to support “view sharing”.

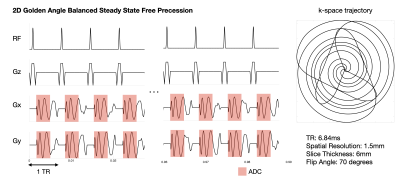

Three real-time scans were tested in this new framework: spiral GRE and spiral bSSFP of human speech, and spiral bSSFP of cardiac function. Experiments were performed using a whole body 0.55T system (prototype MAGNETOM Aera, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with high-performance shielded gradients (45 mT/m amplitude, 200 T/m/s slew rate). Images were acquired using RTHawk and Pulseq and image quality was compared. Reconstructions were based on a view-sharing NUFFT [6] and sum-of-squares coil combination. Figures 2 and 3 show the pulse sequence diagrams for the sequences used. The reconstruction server was a Lambda Hyperplane compute-server with 32 core CPUs and 512 GB of memory. For reproducibility, code will be shared prior to ISMRM.

Latency was measured by monitoring the server before and after network communications, and before and after reconstruction. Latency measurements were completed for both acquisition and reconstruction.

Results

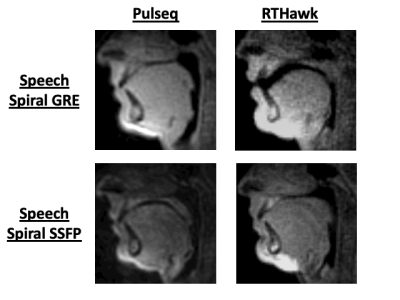

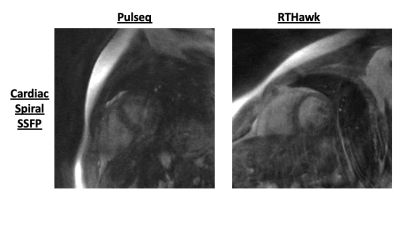

Figures 4 and 5 shows results comparing RTHawk scans and Pulseq scans for mid-saggital speech production imaging with a “count 1 to 5” stimulus, and short-axis imaging of left ventricular function. The temporal and spatial resolutions are slightly different due to the hardware differences between the RTHawk console and the SpinBench encoded hardware constraints (see Discussion). For the speech sequences, the latency of acquisition was 37.5ms with a latency of reconstruction of 33.44ms for a total latency ~70ms. For the cardiac data, a 2X undersampled acquisition latency was 460ms and reconstruction latency was 310ms.Discussion

Converted waveforms do not match precisely between Pulseq and RTHawk, since in RTHawk the gradient waveforms are always set to max out hardware performance. In Pulseq, if max gradient amplitude and slew rate are used, the scanner refuses and asks for reduced hardware usage. Therefore, RTHawk scans are slightly modified from what is noted in the original SpinBench files, changing spatial and temporal resolution slightly. Fixing this discrepancy remains future work.As data is streamed it is dealt with immediately by the server. Because the overall reconstruction latency is greater than the acquisition time, this causes a build-up of reconstructions that makes the time from acquisition-to-image progressively take longer. One solution is to reduce reconstruction latency by moving from MATLAB to custom compiled C/C++ or using the Gadgetron’s MRD server. Another is to perform reconstruction with priority, by buffering older acquisitions in favor of new to get the most “up-to-date” image. Alternatively, better compute-hardware or networking equipment can improve performance.

Latency measurements for acquisition and reconstruction are highly dependent on the amount of activity occurring on the server. A dedicated server for on-line reconstruction should be used to have more consistent acquisition and reconstruction latency results.

There are several limitations with the current SpinBench conversion. Currently, only a single RF pulse per TR is supported. Also, the conversion is not written in the design philosophy of Pulseq. Pulseq files usually consist of several blocks and timing, where each block consists of easy-to-read components. Currently, we put all elements, RF, ADC, and gradient events into a single block per TR and put all shape information into custom encodings. While this allows for rapid sharing of the existing waveforms, it is not conducive to easy modifications such as readout time or echo time which would be easy to make in standard Pulseq code. It remains future work to parse the timing information from SpinBench files to create Pulseq files that are easily readable.

Conclusion

We demonstrate an open-source sharing of real-time interactive MRI, which can facilitate reproducible research with acceptable latency for real-time imaging but not yet for real-time interaction.Acknowledgements

We acknowledge grant support from the National Science Foundation (#1828736) and research support from Siemens Healthineers. We also acknowledge Ye Tian for his expertise and help with the cardiac sequence, localization, and reconstruction.References

[1] M. Veldmann, P. Ehses, K. Chow, J.-F. Nielsen, M. Zaitsev, and T. Stöcker, “Open-Source MR Imaging and Reconstruction Workflow,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. n/a, no. n/a, doi: 10.1002/mrm.29384.

[2] M. S. Hansen and T. S. Sørensen, “Gadgetron: An open source framework for medical image reconstruction,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 69, no. 6, pp. 1768–1776, 2013, doi: 10.1002/mrm.24389.

[3] Y. Lim and K. S. Nayak, “Real-time MRI of speech production at 0.55 Tesla,” presented at the ISMRM, vol. 2022, p. 0755.

[4] J. M. Santos, G. A. Wright, and J. M. Pauly, “Flexible real-time magnetic resonance imaging framework,” Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc, vol. 2004, pp. 1048–1051, 2004, doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2004.1403343.

[5] K. J. Layton et al., “Pulseq: A rapid and hardware-independent pulse sequence prototyping framework,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 77, no. 4, pp. 1544–1552, 2017, doi: 10.1002/mrm.26235.

[6] J. A. Fessler and B. P. Sutton, “Nonuniform fast fourier transforms using min-max interpolation,” IEEE Trans. Signal Process., vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 560–574, Feb. 2003, doi: 10.1109/TSP.2002.807005.

Figures

Figure 2: a) A spoiled gradient echo spiral sequence for real-time speech MRI. An 8-interleaf spiral acquisition with a spatial resolution of 2.64mm, slice thickness of 7mm, flip angle of 15 degrees. The SpinBench equivalent scan had a slightly different spatial resolution at 2.4mm and a TR of 7.81ms with all other parameters the same.

b) A bSSFP sequence for real-time Speech MRI. A 13-interleaf spiral acquisition with spatial resolution fo 2.6mm, slice thickness 6mm, flip angle 35 degrees. The SpinBench equivalent scan had a spatial resolution of 2.3mm and TR of 5.05ms.