2396

SimMRI – A web-based MR Image Simulator for easy accessible MRI teaching1Chair for Computer Assisted Clinical Medicine, MIiSM, Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg University, Mannheim, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Software Tools, Simulations, Education

SimMRI is a Web-Based MRI simulator developed for teaching students. It allows the simulation of multiple sequences for 1H and 23Na imaging on different brain datasets. The software enables users to customize parameters for each sequence, add noise, or change the voxel count for every dimension of the image. Additionally, the software provides compressed sensing reconstruction with three k-space subsampling schemes. The computation is solely performed on the client and therefore well suited for large student groups. The code, written in JavaScript, HTML, CSS, and c compiled to WebASM, is open source and supports easy inclusion of new sequences.Introduction

Teaching MRI to (medical) students is challenging, yielding the urgent need to make MRI more accessible to students. Hence, a simulator for MR imaging can cross the gap from a theoretical discussion of sequences to the actual image. In contrast to just displaying an image, a simulator enables to self-study the underlying principles and influences of parameters that affect the MR image. In the past years, we have used the simulator by Hackländer et. al. [1] in our seminars, but students could only use it during the session and not at home while learning. A newer, also web-based, simulator by Treceño-Fernández et al. [2] was recently presented. It has a workflow that is close to real MRI devices and a server performs the image simulation, which might demand high resourcesTherefore, we developed a web-based simulator, which focuses on the sequence simulation and performs computation inside the browser to be used ubiquitous.

Methods

We use freely available head phantoms[3][4][5] and assign the appropriate tissue parameters (T1,T2 proton density) values to the corresponding compartments. Based on this, we generated six datasets (two for 3T 1H and 23Na, three for 1.5T 1H and one 1T 1H) to simulate the signal for different sequences in each compartment.Ten sequences were implemented, six for 1H MRI and three for 23Na. These sequences include the basic Spin Echo, Inversion Recovery, Spoiled GRE and some more advanced steady state sequences. The sodium MRI sequences include GRE, single quantum Spin Echo and triple quantum spin echo.

In addition to the simulation of sequences, we have options to add noise to the images. Currently, the addition of Gaussian noise to the k-space is supported. The user can decide whether to use 2D or 3D Fourier Transform and k-space. This does not change the initial image simulation, which is performed in image space, only the calculation of the k-space and all further uses of the fourier transform. The (inverse) Fourier calculation is used after noise was added to the k-space to calculate the resulting noisy image and by the compressed sensing algorithm. When the number of voxels are reduced, it is possible to choose one of three different interpolation modes, Nearest neighbor, average of the 8 nearest neighbors and the average over all datapoints in the dataset that would be within the image voxel.

We have also implemented a compressed sensing algorithm[6]. Three methods for undersampling the k-space are provided, randomly, pseudo-randomly where the center is sampled fully with decreasing probability towards the edges, and a regularly spaced sampling.

All these options for noise, 2D/3D, image resolution, and compressed sensing can be combined and used with every sequence and dataset.

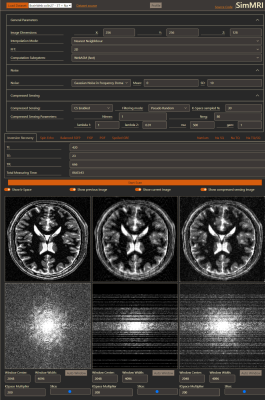

When simulating fully and undersampled images, both images can be shown side by side to easily compare the result of changed parameters or a different sequence. A simulation run with compressed sensing generates three different images, one shows the simulated image with a fully sampled k-space, the second shows the images with the undersampled k-space using the selected sampling scheme, and the third is the result where the compressed sensing algorithm filled up the undersampled k-space. These three images can also be displayed side by side (Fig 1).

Results

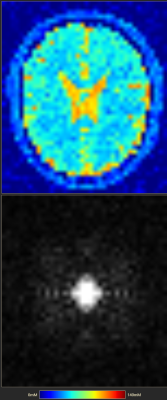

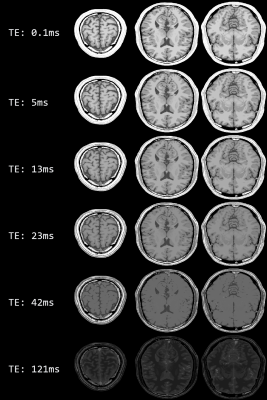

A sample of our user interface shows the results for a simulation with compressed sensing (Fig. 1). In Fig 2 contains the results of 23Na spin echo (TE: 0.3ms, TR: 666ms). It is simulated with an approximate voxel size of 5mmx5mmx5mm and added Gaussian noise. In Fig 3 are several simulated images for a Spin Echo sequence with different TE between 0.1ms and 121ms. Every row shows the slices at the same position.Discussion

Offloading all computation to the client allows us to support many users simulating images simultaneously without the need for an expensive, high-performance server.The selection of sequences was based on our lectures, so the students can use all sequences we reference. We included sodium sequences due to the increasing interest in 23Na MRI.

Compressed sensing was added to show how image acquisitions can be accelerated, even though it leads to longer computation time in a simulator.

In summary, we developed a simulator for teaching MRI to students from non-technical courses. It is freely available ( https://github.com/ChristianToennes/SimMRI ), runs on any modern browser and can be easily extended by further sequences or reconstruction techniques.

Acknowledgements

This research project is partly supported of the Research Campus M2OLIE funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) within the Framework “Forschungscampus: public-private partnership for Innovations” under the funding code 13GW0388A.References

[1] T. Hackländer and H. Mertens, “Virtual mri: A pc-based simulation of a clinical mr scanner” Academic Radiology, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 85–96, 2005.

[2] D. Treceño-Fernández, J. Calabia-del Campo, M. L. Bote-Lorenzo, E. G. Sánchez, R. de Luis-García, and C. Alberola-López, “A web-based educational magnetic resonance simulator: Design, implementation and testing,” Journal of Medical Systems, vol. 44, no. 1, p. 9, 2019.

[3] B. Aubert-Broche, M. Griffin, G. Pike, A. Evans, and D. Collins, “Twenty new digital brain phantoms for creation of validation image data bases,” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 25, no. 11, pp. 1410–1416, 2006.

[4] C. J. Holmes, R. Hoge, L. Collins, R. Woods, A. W. Toga, and A. C. Evans, “Enhancement of mr images using registration for signal averaging,” Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography, vol. 22, no. 2, 1998.

[5] B. Alfano, M. Comerci, M. Larobina, A. Prinster, J. P. Hornak, S. E. Selvan, U. Amato, M. Quarantelli, G. Tedeschi, A. Brunetti, and M. Salvatore, “An mri digital brain phantom for validation of segmentation methods,” Medical Image Analysis, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 329–339, 2011.

[6] T. Goldstein and S. Osher, “The split bregman method for l1-regularized problems,” SIAM Journal on Imaging Sciences, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 323–343, 2009

Figures