2391

ScanHub: Open-Source Platform for MR Scanner Control, Acquisitions and Postprocessing

David Schote1,2, Johannes Behrens2, Lukas Winter1, Christoph Kolbitsch1, and Christoph Dinh2

1Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB), Braunschweig and Berlin, Germany, 2Brain-Link UG (haftungsbeschränkt), Landau i.d. Pfalz, Germany

1Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB), Braunschweig and Berlin, Germany, 2Brain-Link UG (haftungsbeschränkt), Landau i.d. Pfalz, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Software Tools, Software Tools

ScanHub (https://github.com/brain-link/scanhub-ui) is an open, generic solution for cloud-based medical data acquisition and processing. Functionalities are subdivided into microservices supporting use cases in the clinical as well as in the research context. The platform capabilities are demonstrated with an exemplary MRI workflow. As a proof of principle MR data acquisition was simulated with an open-source Bloch solver. A reconstruction of the simulated raw data is provided by a microservice. The whole acquisition process is controlled via a web-based UI; from deploying a pulse sequence to the organization and visualization of reconstructed and DICOMized results.Introduction

A variety of open-source software in the field of MR examinations has already been published, addressing specific subproblems in the image acquisition and processing chain1, 2. These developments include software for: hardware-independent pulse sequence development3-5, MR simulations6, 7, image reconstructions8-10, data formats11, data viewers12, and image post-processing13, 14. ScanHub is a cloud-based open-source software that aims to merge and extend these available open-source software tools to operate open- and closed-source MRI scanners. The current functionality includes: selection of pulse sequences and MR protocols, display of pulse sequence parameters (RF and gradient pulses), performing image reconstructions as well as viewing and exporting data.Methods

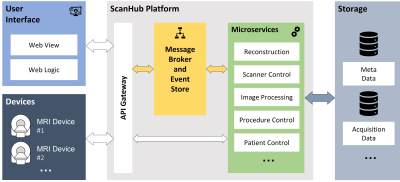

Event-Driven Microservice ArchitectureScanHubs components are containerized17, structuring the platform in frontend, devices, and microservices. The different containers can run on different devices, whereby the setup can be suited to the individual requirements of the clinic or research site. ScanHubs component interfaces are largely built on the fast and performant web framework FastAPI18. By different HTTP routes, the React-based frontend communicates to the API. ScanHubs functionalities are subdivided into microservices. For example, a service for image reconstruction and a service for acquisition control. The division into individual services enables extensibility and scalability, i.e., adaptation to new use cases and execution on remote servers, e.g., cloud resources, see figure 1. This separation also allows easier clearance of certain modules for future regulatory approval whereas others can remain experimental. Each microservice is running as a separate container, allowing the use of different programming languages. The microservices are loosely coupled via a message broker including an event store, fostering extensibility and maintainability. The message broker, which is realized by the open-source Kafka framework receives published messages, which are distributed via topics. According to the respective topic, the message broker sends messages to its subscribers, following the Publish/Subscribe messaging pattern19. Through this mechanism, microservices can be triggered by topic-related events. This message structure enables the organization of various dynamic processing workflows. The browser user interface and the connected MR device communicate with the microservices via the API gateway. Acquisition and processing data are transferred to a data storage.

MR Workflow

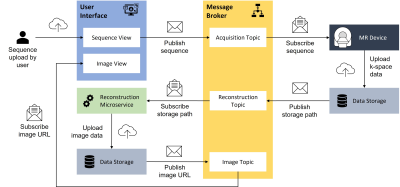

To organize MR acquisitions on the platform, metadata of devices, patients, procedures, and records is stored in a data storage, here a PostgreSQL20 database. The user interacts with the platform through a browser-based react UI. Devices register themselves at the respective device control microservice via an API. It creates dedicated topics for acquisition control and monitoring within the message broker following the already mentioned Publish/Subscribe pattern. To perform an MR acquisition a sequence in the open-source PulSeq framework must be selected or uploaded. When the acquisition is executed, the sequence is communicated to the device. This allows a flexible hardware-independent approach with the interpreter of the PulSeq sequence running on the connected device. For now, the device is a virtual MRI machine that uses an open-source Bloch solver implemented in Python and Julia for simulations 21. The reconstruction of the simulated raw data in DICOM format is provided by a microservice and addressed through the respective topic. It can be run on a dedicated server with sufficient performance. For now, data is reconstructed by FFT, but in general, this can be replaced by any reconstruction framework. The simulated raw and reconstructed DICOM data are stored in an Orthanc22 database. The reconstructed image is visualized in the ScanHub UI enabled by an integrated web-based DICOM viewer 23.

Results

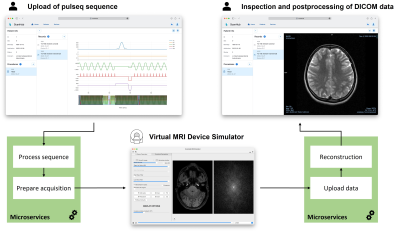

The resulting browser-based react frontend of ScanHub and current functionalities are conducted in figure 3. The user can manage patients, procedures, and records, which are stored in the underlying database. When the user uploads a sequence, parameters are visualized in a sequence diagram (upper left of figure 3). Starting the acquisition triggers microservices, which process the data and perform the simulation in an encapsulated application (bottom center of figure 3). The raw data is reconstructed and uploaded to the Orthanc database. After the recording was successful, the user can view the reconstructed image in the web UI (upper right of figure 3).Discussion and Conclusion

With ScanHub we presented the concept of an open-source, cloud platform for MR scanner control, data acquisition, and data processing. The event-driven microservice architecture enables the integration of different components, which are part of the MR acquisition process. The decentralized and modular structure allows customizable, scalable processing chains, which are easy to maintain. The open-source nature of the project allows transparent workflows and extensions by the MR community. Future developments and testing will include the operation and execution of pulse sequences on realistic MR scanner hardware including: identification, start and stop of the machine, adjustments and tune-up, maintenance protocols, data acquisition, and storing. Further, the platform will be extended by connecting existing open-source reconstruction frameworks.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

- “Open Source Magnetic Resonance Imaging”, https://www.opensourceimaging.org, accessed: November 2022.

- “MR-Hub: Open-access software tools for the ISMRM community”, https://ismrm.github.io/mrhub/, ISMRM, accessed: 08.11.2022.

- K. J. Layton et al., “Pulseq: A rapid and hardware-independent pulse sequence prototyping framework,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 77, no. 4. Wiley, pp. 1544–1552, Jun. 07, 2016. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26235.

- K. Ravi, S. Geethanath, and J. Vaughan, “PyPulseq: A Python Package for MRI Pulse Sequence Design,” Journal of Open Source Software, vol. 4, no. 42. The Open Journal, p. 1725, Oct. 12, 2019. doi: 10.21105/joss.01725.

- J. F. Magland, C. Li, M. C. Langham, and F. W. Wehrli, “Pulse sequence programming in a dynamic visual environment: SequenceTree,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 75, no. 1. Wiley, pp. 257–265, Mar. 07, 2015. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25640.

- G. Tong et al., “Virtual Scanner: MRI on a Browser,” Journal of Open Source Software, vol. 4, no. 43. The Open Journal, p. 1637, Nov. 25, 2019. doi: 10.21105/joss.01637.

- T. Stöcker, K. Vahedipour, D. Pflugfelder, and N. J. Shah, “High-performance computing MRI simulations,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 64, no. 1. Wiley, pp. 186–193, Jun. 23, 2010. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22406.

- M. Blumenthal et al., mrirecon/bart: version 0.8.00. Zenodo, 2022. doi: 10.5281/ZENODO.7110562.

- J. Fessler, M. W. Haskell, T. Hakkel, and C. Lin, “Michigan Image Reconstruction Toolbox (MIRT)”, GitHub, https://web.eecs.umich.edu/~fessler/code/, accessed: November 2022. [ 10 ] H. Xue, S. Inati, T. S. Sørensen, P. Kellman, and M. S. Hansen, “Distributed MRI reconstruction using gadgetron-based cloud computing,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 73, no. 3. Wiley, pp. 1015–1025, Mar. 31, 2014. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25213.

- S. J. Inati et al., “ISMRM Raw data format: A proposed standard for MRI raw datasets,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 77, no. 1. Wiley, pp. 411–421, Jan. 29, 2016. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26089.

- Sedghi, J. Petts and E. Ziegler, “Cornerstone3D DICOM Viewer”, Conerstone.js, https://www.cornerstonejs.org/, accessed: November 2022.

- Fedorov et al. “3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network.” Magnetic resonance imaging vol. 30,9 (2012): 1323-41. doi:10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001.

- Karakuzu et al., “qMRLab: Quantitative MRI analysis, under one umbrella,” Journal of Open Source Software, vol. 5, no. 53. The Open Journal, p. 2343, Sep. 03, 2020. doi: 10.21105/joss.02343.

- Thomas O'Reilly, “Flexible Magnet Design at Low Field”, ISMRM Workshop on Low-Field MRI, March 2022.

- Winter L., “OSI2 ONE: An Open-Source Low-Field MR Scanner”, ISMRM Workshop on Low-Field MRI, March 2022.

- O. Bentaleb, A. S. Z. Belloum, A. Sebaa, and A. El-Maouhab, “Containerization technologies: taxonomies, applications and challenges,” The Journal of Supercomputing, vol. 78, no. 1. Springer Science and Business Media LLC, pp. 1144–1181, Jun. 08, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11227-021-03914-1.

- S. Ramírez, “FastAPI (0.86.0)”, GitHub, https://github.com/tiangolo/fastapi, accessed: 2022.

- K. Birman and T. Joseph, “Exploiting virtual synchrony in distributed systems,” ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review, vol. 21, no. 5. Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), pp. 123–138, Nov. 1987. doi: 10.1145/37499.37515.

- M. Stonebraker and L. & Rowe, “The design of POSTGRES”, Conference on Management of Data, 1986.

- C.-P. Carlos, cncastillo/KomaMRI.jl. Zenodo, 2021. doi: 10.5281/ZENODO.6627503. [ 22 ] S. Jodogne, “The Orthanc Ecosystem for Medical Imaging,” Journal of Digital Imaging, vol. 31, no. 3. Springer Science and Business Media LLC, pp. 341–352, May 03, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s10278-018-0082-y.

- Sedghi, J. Petts and E. Ziegler, “Cornerstone3D DICOM Viewer”, Conerstone.js, https://www.cornerstonejs.org/, accessed: November 2022.

Figures

Overview of ScanHub

components, including interfaces for users and devices. Via an API gateway, the devices and the user

interface can communicate with the microservices directly or via a message

broker. The message broker is also used for communication between the

microservices. These applications perform different tasks of the acquisition

process with access to different data stores.

Workflow diagram for a simplified MR image acquisition

process. A sequence is uploaded by the user interface and send to the MR device,

the reconstructed image can be viewed in the user interface. The communication

is managed by the message broker through different topics.

Exemplary workflow of

ScanHub as a web-based react frontend, which allows the organization and execution

of records. The user can upload and view a sequence, trigger the acquisition

and view the results. Once an acquisition is triggered, a virtual MRI device

simulates the acquisition and triggers the corresponding data processing steps.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/2391