2375

Tailored multi-dimensional partial saturation pulses for inner/outer-volume spoiled steady-state imaging

Jon-Fredrik Nielsen1 and Kawin Setsompop2,3

1fMRI Laboratory and Biomedical Engineering, University Of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States, 2Radiology, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, United States, 3Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, United States

1fMRI Laboratory and Biomedical Engineering, University Of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States, 2Radiology, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, United States, 3Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Pulse Sequence Design, RF Pulse Design & Fields

We propose to use short (~1–1.5ms) multi-dimensional spatially selective RF pulses that saturate unwanted signal regions in spoiled gradient echo (SPGR/FLASH/T1-FFE) imaging. These pulses can be inserted at regular intervals in the sequence, e.g., immediately before each imaging excitation pulse. By reducing signal contamination from outside the region of interest (ROI), these pulses should enable more rapid and robust T1- and T2*-weighted imaging in many body and neuro applications.Introduction

In many MRI applications, only part of the acquired image volume is of interest to the researcher or clinician. For example, in some functional brain imaging studies, only the cortical signal is of interest, and in many body imaging applications (e.g., cardiac, breast, prostate) the region of interest (ROI) occupies a relatively small fraction of the entire field-of-view (FOV) required to avoid aliasing artifacts. The need to encode a much larger volume than the ROI can limit the spatio-temporal resolution and image quality; the latter can be due to, e.g., motion or physiological noise from non-ROI regions, or reduced parallel imaging performance.Here we propose to use short (~1.5ms) 3D spatially selective saturation radiofrequency (RF) pulses that suppress unwanted (non-ROI) signal regions in spoiled gradient-echo (SPGR/FLASH/T1-FFE) steady-state imaging, which are designed to be suitable for use on conventional scanners with standard body coil RF transmit hardware. By inserting these pulses at regular intervals during the sequence (e.g., every TR), the steady-state non-ROI suppression is greater than that of a single pulse, which relaxes the design requirements and enables very short pulses (Fig. 1). We demonstrate this strategy by designing and validating an inner-volume (IV) saturation pulse that is suitable for “MR Corticography” [1], i.e., outer-volume (OV) T2*-weighted functional brain imaging; the benefit of IV suppression in that application is improved parallel imaging performance (reduced g-factor) by suppressing signal from the central regions where coil sensitivities are the least orthogonal, and reduced physiological noise from pulsating CSF in the large ventricles.

Methods

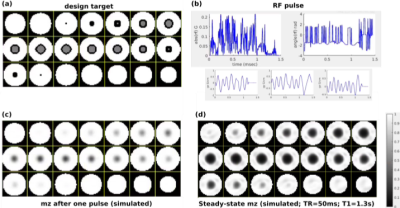

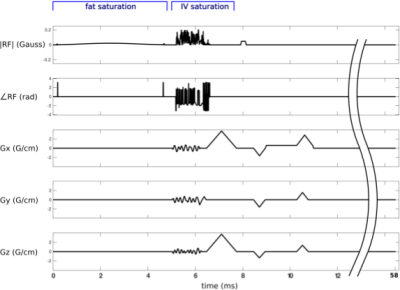

RF pulse design: We used the auto-differentiation approach in [2] to jointly optimize the RF and gradient waveforms for the design target in Fig. 1(a). We performed the optimization in two stages: We first initialized the gradient with a 1ms SPINS pulse [3] (α=5, β=0.5, duration=1ms, u=12*pi, v=2*pi, resolution=6cm) and optimized the waveforms on a coarse (20us) raster. We then added a ~0.5ms area-preserving ramp to zero on each gradient axis, interpolated the waveforms to 4us, smoothed the gradients with a moving average filter of width 52 us, and redesigned the RF waveform. The design was performed prior to the imaging sessions and did not consider the subject’s B0 inhomogeneity.Experimental validation: We scanned a volunteer on a GE 3T MR750 scanner with a Nova 32ch head coil under IRB approval, in two separate sessions. In Session 1, we chose SPGR sequence parameters that match a typical 3D BOLD fMRI experiment (TR=58ms; 3mm isotropic resolution), except we used a single-echo (spin-warp) readout to avoid B0 distortion and other EPI artifacts (Fig. 3). We also acquired a reference image with identical parameters except the saturation RF waveform amplitude was set to zero. In Session 2, we acquired a 3D SPGR image with 1.5mm isotropic resolution and minimum TR (8.5ms). The saturation RF pulse amplitude for Session 2 was scaled by the factor sqrt(8.5ms/58ms)=0.37, such that the SAR was equivalent in both experiments.

Results

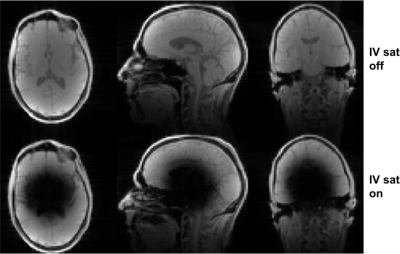

Figure 4 shows the volunteer imaging results from Session 1 (TR=58ms; 3mm isotropic resolution), which are in good agreement with the simulated steady-state magnetization (Fig. 1(d)). Figure 5 shows the results from Session 2 (TR=8.5ms; 1.5mm isotropic resolution), and shows that image contrast in the OV region is well preserved compared to the reference acquisition. The scanner’s SAR monitor reported a value of about 0.8 W/kg in a 150 lb subject, well under the 3.2 W/kg 10s limit.Discussion

ROI shape and placement: For simplicity, in this proof-of-concept study we designed the RF pulse prior to the scan sessions, using a spherical target pattern centered at scanner iso-center. In the future, the shape and placement of the ROI can be tailored to the subject’s anatomy. SAR: If needed, SAR can be mitigated by, e.g., (1) reducing the RF amplitude, (2) using VERSE [4], or (3) penalizing high SAR during the design. IV imaging: The proposed strategy should work equally well for IV imaging (OV suppression). It should also work for suppressing more than one region simultaneously (e.g., in breast imaging) and for more complex regions, though those extensions may require longer RF pulse durations or more advanced hardware. Compatibility with emerging gradient and parallel transmit hardware: The proposed pulses are slew-limited and will benefit from fast head gradient systems. Our approach is also compatible with parallel transmit systems. Such hardware improvements should enable more complex saturation patterns, and may enable, e.g., spectral-spatial pulses that suppress both fat and non-ROI tissue simultaneously.Conclusion

We have demonstrated that very short 3D RF pulses with moderate SAR can suppress unwanted signal regions in SPGR/FLASH imaging on conventional whole-body MRI scanners. We believe these pulses could be useful for a wide range of T1/T2*-weighted imaging applications such as MR corticography, cardiac first-pass perfusion, and prostate imaging. It should also be possible to use the proposed strategy in magnetization-prepared SPGR sequences (e.g., MP-RAGE), provided that transient mz saturation effects are considered.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH Grants R21AG061839, U24NS120056, U01-EB025162.References

[1] Jun Ma, Xinqiang Yan, Bernhard Gruber, Jonathan Martin, Zhipeng Cao, Jason Stockmann, Kawin Setsompop, and William Grissom, ISMRM 2020, p3696.

[2] Luo T, Noll DC, Fessler JA, Nielsen JF. Joint Design of RF and Gradient Waveforms via Auto-differentiation for 3D Tailored Excitation in MRI. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2021 Dec;40(12):3305-3314. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2021.3083104.

[3] Malik SJ, Keihaninejad S, Hammers A, Hajnal JV. Tailored excitation in 3D with spiral nonselective (SPINS) RF pulses. Magn. Reson. Med. 2012; 67: 1303–1315.

[4] Hargreaves BA, Cunningham CH, Nishimura DG, Conolly SM. Magn Reson Med. 2004 Sep;52(3):590-7.

Figures

Figure 1. Inner-volume signal suppression in spoiled steady-state imaging using a 1.5ms 3D tailored RF pulse (Bloch simulation). (a) The target longitudinal magnetization (mz) equals 1 (equilibrium magnetization) in the outer-volume and 0.5 in the IV. Black indicates don’t-care regions. (b) RF pulse designed using the approach in [2]. (c) Simulated mz after application of the pulse in (b) once. (d) Predicted steady-state mz based on the Ernst equation, using the result from (c). The predicted IV signal suppression is excellent, at the cost of some inhomogeneity in mz in the OV.

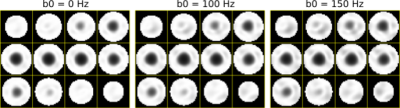

Figure 2. Robustness of the steady-state longitudinal magnetization to b0 inhomogeneity (off-resonance), Bloch simulation results. The first 1ms of the proposed RF pulse (i.e., prior to adding the area-preserving ramp to zero) was simulated for a spherical object with constant (global) b0 offsets of 0, 100, and 150 Hz. For comparison, the b0 inhomogeneity in the brain at 3T is typically +/- 100-150 Hz.

Figure 3. Pulse sequence diagram for the low-resolution 3D SPGR sequence used in volunteer imaging Session 1. A fat saturation pulse is followed by the proposed IV sat pulse and a crusher gradient. The imaging pulse is a 15 degree hard pulse. TR=58ms; FOV=24x24x24cm; matrix size 80x80x80. By replacing the spin-warp readout by an EPI train, this sequence could be used for BOLD fMRI (MR corticography).

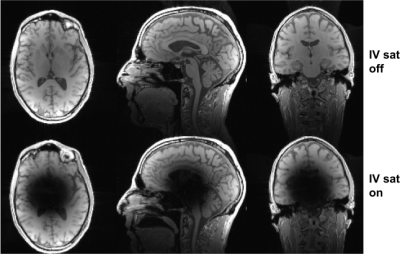

Figure 4. In vivo 3D SPGR imaging results using the sequence in Fig. 3 (bottom row), and the same sequence except with the saturation pulse RF amplitude set to zero (top row). The proposed RF pulse successfully saturates the IV region while having minimal impact on the OV region. Acquisition parameters: 3mm isotropic resolution; flip=15 deg; TR=58 ms.

Figure 5. Session 2 imaging results without (top row) and with (bottom row) IV saturation. The acquisition was similar to that shown in Fig. 3, except no fat saturation was used. The inner volume (IV) is suppressed in the bottom row, while tissue contrast is similar for both acquisitions in the outer-volume (OV) regions. Acquisition parameters: 1.5mm isotropic resolution; flip=12 deg; TR=8.5ms.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/2375