2349

Distance-dependent changes in functional connectivity in neonatal brain1Key Laboratory for Biomedical Engineering of Ministry of Education, Department of Biomedical Engineering, College of Biomedical Engineering & Instrument Science, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Neonatal, fMRI (resting state)

The present study aimed to explore functional connectivity changes with anatomical distance in neonatal brain by using the second dHCP resting-state fMRI dataset. We calculated distance-dependent functional connectivity density (FCD) maps to test for the effect of age, preterm-birth, and gender. Results found that the FCD in neonatal brains showed distance-dependent changes with PMA, in which the short- and long-range FCD changes were associated with maternal environment and postnatal experience, respectively. Moreover, the preterm- and term-born infants showed different patterns in short- and long-range FCD. These findings suggested distance-dependent changes in functional connectivity in neonatal brain during early development.Introduction

The human brain undergoes significant and rapid developments from mid-fetal stage to neonatal period 1,2. Recent studies have revealed a maturation of functional connectivity in low-order but not high-order networks in neonatal brain 3, which shows an individual variability 4 during early brain development. However, the functional connections between different regions are closely associated with their anatomical locations 5,6, which is not considered in previous studies. In this study, we used functional connectivity density (FCD) method to investigate the effects of age, preterm, and gender on short- and long-range FCD with a distance threshold in the neonates.Methods

Data acquisition: We used the second release of the Developing Human Connectome Project (dHCP) neonatal data. After a strict screening for head motion and PMA, 280 infants (preterm : term = 36:244) with PMA ranged from 38 to 44 weeks entered into subsequent analysis. 19 infants included two sessions that were scanned at different ages.Data processing: Following by the dHCP fMRI pipeline 7, white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, and six head motion parameters were regressed as the nuisance variables. Then, the data underwent spatially normalization, smoothing and filter with a pass band of 0.01- 0.1Hz. Subsequently, we calculated three FCD maps (global FCD (gFCD), long-range FCD (lFCD) and short-range FCD (sFCD)) with a distance criterion of 12 mm 8 for each subject. Among them, the gFCD was derived by averaging the absolute Pearson correlations coefficient between time series of a voxel and those of all other voxels in the whole brain, and the sFCD and lFCD only considered voxels with anatomical distance less than 12 mm and greater than 12 mm, respectively. Finally, we calculated the laterality index (LI) 9 for each FCD map using the following equation: LI = (Left – Right) / (Left + Right).

Statistical analysis: We performed cross-subject analysis using general linear models (GLM) to test for the effect of PMA, GA (term-born neonates with PMA-GA < 1 week), ∆PMA (term-born neonates with two scans), preterm, and gender on the FCD and its laterality 7. The false discovery rate (FDR) correction was used to control the false discoveries due to multiple comparisons in whole brain analysis. We also used different methods to validate our results, including different FCD calculation methods (e.g., positive vs absolute correlation, and weighted vs binarized connectivity) and distance thresholds (e.g., 6mm, 12mm and 18 mm). To further capture the behavioral relevance of the identified development-related FCD, we tested the associations of FCD with behavioral domains via the Neurosynth (https://neurosynth.org/).

Results

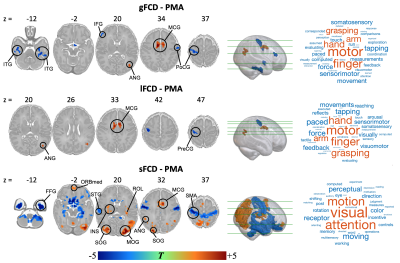

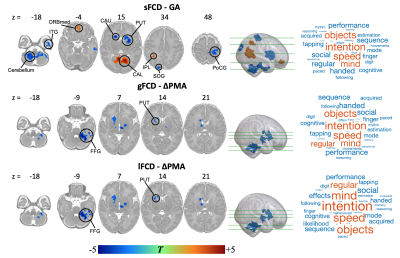

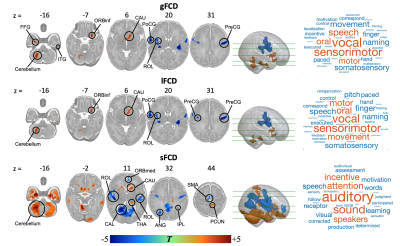

Three averaged FCD maps in term-born infants at each week PMA were shown in Fig. 1. Both gFCD and lFCD showed significant correlations with PMA in postcentral gyrus (PoCG) and middle cingulate gyrus, whereas the sFCD showed significant correlations with PMA in wider brain regions than gFCD and lFCD, including orbitofrontal cortex (ORB), rolandic operculum (ROL), supplementary motor area (SMA), superior occipital gyrus (SOG), calcarine cortex (CAL), insula and superior temporal gyrus (STG) (adjusted p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). Moreover, we only found significant correlations between sFCD and GA in the PoCG, ORB, inferior parietal lobe (IPL), SOG, inferior temporal gyrus (ITG), caudate and cerebellum (adjusted p < 0.05). However, the correlation between FCD and ∆PMA in fusiform gyrus (FFG) was observed in both gFCD and lFCD but not in sFCD (adjusted p > 0.05) (Fig. 3).Importantly, compared with term-born neonates, preterm-born neonates showed altered gFCD and lFCD in the lingual gyrus, ITG, caudate, ROL, PoCG and precentral gyrus (PreCG), and abnormal sFCD in the SMA, IPL, precuneus, CAL, thalamus and cerebellum (adjusted p < 0.05) (Fig. 4). Additionally, there was no significant difference between male and female, and all statistical results of the LI did not pass the FDR correction (adjusted p > 0.05). The validation analysis showed that our primary findings were robust, which were not affected by different FCD calculation and distance thresholds.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, we explored the distance-dependent changes of FCD and its laterality with the development of neonatal brain for the first time. Our results demonstrated that 1) the FCD in neonatal brains showed significant distance-dependent changes with PMA. And, the long- and short-range connection changes were associated the motor and visual-motor attention functional developments in neonates, respectively; 2) the short- and long-range connectivity respectively correlated with the GA and the ∆PMA, suggesting that they were separately modulated by the maternal environment and postnatal experience, which might be supported by a previous finding 10 that showed similar local activity but lower connections between regions in neonates compared with adults; 3) the FCD showed more differences between preterm and term in the short-range connectivity than long-range connectivity in the frontotemporal regions, and preterm has an effect on the developments of the sensorimotor, auditory and language functions, which was consistent with a prior study 3 that the auditory, sensorimotor and frontotemporal-related networks showed abnormal functional connectivity in preterm neonates. In summary, the results revealed distance-dependent changes of functional connectivity in neonatal brain with age, and differences of that between preterm- and term-born neonates. This provides a new insight toward the underlying mechanism of early brain functional development.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (2018YFE0114600, 2021ZD0200202), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81971606, 82122032), and the Science and Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (202006140, 2022C03057).References

1. Kostović, I., & Jovanov-Milošević, N. (2006, December). The development of cerebral connections during the first 20–45 weeks’ gestation. In seminars in fetal and neonatal medicine. WB Saunders. 2006; 11(6): 415-422.

2. Ouyang, M., Dubois, J., Yu, Q., Mukherjee, P., & Huang, H. Delineation of early brain development from fetuses to infants with diffusion MRI and beyond. Neuroimage. 2019; 185:836-850.

3. Eyre, M., Fitzgibbon, S. P., Ciarrusta, J., Cordero-Grande, L., Price, A. N., Poppe, T., ... & Edwards, A. D.. The Developing Human Connectome Project: typical and disrupted perinatal functional connectivity. Brain. 2021; 144(7): 2199-2213.

4. Xu, Y., Cao, M., Liao, X., Xia, M., Wang, X., Jeon, T., ... & He, Y. Development and emergence of individual variability in the functional connectivity architecture of the preterm human brain. Cereb Cortex. 2019, 29(10): 4208-4222.

5. Achard, S., Salvador, R., Whitcher, B., Suckling, J., & Bullmore, E. D. A resilient, low-frequency, small-world human brain functional network with highly connected association cortical hubs. Neuroscience. 2006; 26(1): 63-72.

6. Liang, X., Zou, Q., He, Y., & Yang, Y. Coupling of functional connectivity and regional cerebral blood flow reveals a physiological basis for network hubs of the human brain. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013; 110(5): 1929-1934.

7. Fitzgibbon, S. P., Harrison, S. J., Jenkinson, M., Baxter, L., Robinson, E. C., Bastiani, M., ... & Andersson, J. The developing Human Connectome Project (dHCP) automated resting-state functional processing framework for newborn infants. Neuroimage. 2020; 223:117303.

8. Beucke, J. C., Sepulcre, J., Talukdar, T., Linnman, C., Zschenderlein, K., Endrass, T., ... & Kathmann, N. Abnormally high degree connectivity of the orbitofrontal cortex in obsessive-compulsive disorder. JAMA Psychiat. 2013; 70(6): 619-629.

9. Steinmetz, H. Structure, function and cerebral asymmetry: in vivo morphometry of the planum temporale. Neurosci Biobehav R. 1996; 20(4): 587-591.

10. Huang, Z., Wang, Q., Zhou, S., Tang, C., Yi, F., & Nie, J. Exploring functional brain activity in neonates: A resting-state fMRI study. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2020; 45: 100850.

11. Smyser, C. D., Dosenbach, N. U., Smyser, T. A., Snyder, A. Z., Rogers, C. E., Inder, T. E., ... & Neil, J. J. Prediction of brain maturity in infants using machine-learning algorithms. NeuroImage. 2016; 136: 1-9.

Figures

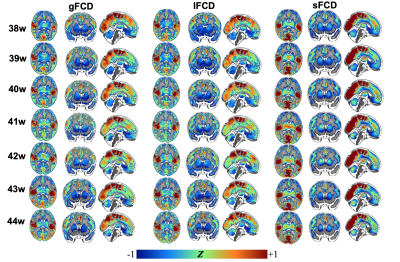

Figure 1. The distance-dependent FCD maps in term-born infants at each week PMA. Group-averaged z-map of FCD in term-born infants scanned at 38-44 weeks PMA. gFCD: global FCD; lFCD: long-distance FCD; sFCD: short-distance FCD.

Figure 2. Relationship between FCD and PMA in term-born infants. Color bar represents T values. The brain regions with red and blue indicate positive and negative correlation between FCD and PMA at scan, respectively. The word cloud represents the behavioral relevance with FCD, the larger the font, the higher the correlation. The long- and short-range FCD changes with the PMA were associated with motor function and visual-motor attention function, respectively.

Figure 3. Relationship between FCD and GA/∆PMA in term-born infants. Color bar represents T values. The brain regions with red and blue indicate positive and negative correlation respectively. The short-range connection changes with GA and long-range connection changes with ∆PMA were associated with maternal environment and postnatal experience, respectively. The changes of FCD with age were correlated with the intention-related functional development.

Figure 4. Effect of preterm birth on distance-dependent FCD. Color bar represents T values. The brain regions with red and blue indicate increased and decreased FCD in preterm-born infants compared with term-born infants, respectively. The FCD shows dependent-distance difference between term-born and preterm-born infants, and may indicate that preterm birth has an effect on the devepolment of the sensorimotor, auditory and language functions.