2348

Cerebral perfusion in neonates with severe congenital heart disease1Pediatric Cardiology, Pediatric Heart Center, Department of Surgery, University Children's Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 2Center for MR-Research, University Children's Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 3Children's Research Center, University Children's Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 4Department of Neonatology, University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 5Child Development Center, University Children's Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 6Department of Neonatology and Pediatric Intensive Care, University Children's Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Synopsis

Keywords: Neonatal, Arterial spin labelling

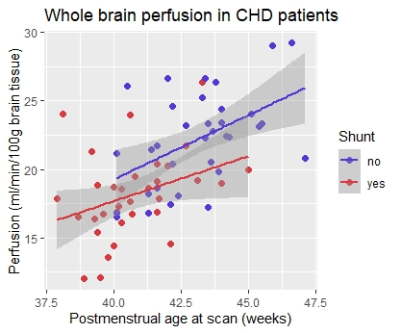

We aimed to compare cerebral perfusion in neonates with severe congenital heart disease (CHD) and healthy controls using arterial spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging. Sixty-seven scans of CHD patients and 23 scans of controls were analyzed (postmenstrual age at scan 41.6±1.8 and 41.9±2.1 weeks, respectively). As in healthy neonates, cerebral perfusion in CHD patients increased with age. Whereas age-adjusted whole brain perfusion was similar to controls, redistribution of regional perfusion was detected in CHD patients. Furthermore, the presence of a systemic-to-pulmonary shunt was associated with cerebral hypoperfusion. Effects of cerebral perfusion alterations on neurodevelopment need to be further assessed.Introduction

Infants with severe congenital heart disease (CHD) undergoing early cardiac surgery are at risk for perioperative brain injuries and neurodevelopmental impairment1,2. An abnormal cerebral blood supply in these patients may limit optimal brain development. Previous studies have shown that preoperative cerebral perfusion is decreased in most severe CHD patients with cyanotic disease3, but studies including postoperative perfusion measurements are lacking.Arterial spin labeling (ASL) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows for the non-invasive assessment of cerebral perfusion and is therefore suitable for use in neonates. The aim of this study was to compare regional and global cerebral perfusion in CHD and healthy neonates.

Methods

Secondary analysis of subjects recruited in two prospective cohort studies between 2013 and 2020. Patients with severe congenital heart disease undergoing cardiac surgery within the first six weeks of life, and healthy controls were included. MRI scans were conducted pre- and/or postoperative to cardiac surgery, as well as at one neonatal time point in healthy controls.Cerebral perfusion images were acquired with a background-suppressed pulsed continuous arterial spin labeling (pCASL) sequence using a 3D stack of spirals readout with a post-labeling delay of 2 seconds. Scans were performed with a 3T GE MR750 MRI scanner. pCASL perfusion images were reconstructed with the vendor-provided perfusion quantification software. The perfusion images were normalised to a study specific, neonatal perfusion template using the linear registration tool in FSL. T1-correction for the effect of hematocrit on perfusion values was applied.4

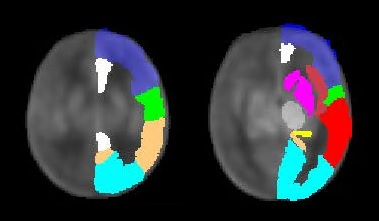

Perfusion was assessed in ten grey matter regions (basal ganglia, thalamus, paracentral region, frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital lobe, hippocampus, insula, cingulate gyrus) using the Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) atlas masks5. Whole brain perfusion was defined as the average of all measured grey matter regions, and relative regional perfusion was calculated by dividing regional by whole brain perfusion. Age-dependent change (with postmenstrual age) and group-related differences (CHD vs. healthy controls) in cerebral perfusion were evaluated using a linear mixed effects model adjusting for repeated measures in patients with pre- and postoperative scans. Subgroup analysis was conducted to evaluate differences in patients with vs. without systemic-to-pulmonary shunt, adjusting for age and repeated measures. Alpha significance level was set to 0.05 for this exploratory analysis.

Results

The study group consisted of 78 neonates, including 55 (71%) CHD patients and 23 (29%) healthy controls. 47 (85%) patients had biventricular, 8 (15%) univentricular CHD. Ninety MRI scans (30 pre-, 37 postoperative, 23 controls) were available for data analysis. Systemic-to-pulmonary shunt was present in a total of 33 (49%) CHD scans (28 (93%) pre- and 5 (14%) postoperative scans).Gestational age (39.4±1.3 vs 39.2±1.4 weeks), body weight (3340±500 vs. 3220±360 grams) and head circumference (34.8±1.4 vs. 34.6±1.1 cm) at birth were similar between CHD and controls. Postmenstrual age at scan was similar with 41.6±1.8 weeks for CHD and 41.9±2.1 weeks for control scans (p=0.55).

An age-dependent increase of perfusion was found in all analyzed brain regions. No evidence for a significant difference in whole brain perfusion was detected between CHD and controls, although a trend-level increase was seen in the CHD group (p=0.06). Significant regional hyperperfusion in CHD was shown in basal ganglia (p=0.034), hippocampus (p=0.006), insula (p=0.026) and temporal lobe (p=0.028) as compared to controls. Looking at relative regional perfusion, we found a significant regional redistribution of cerebral perfusion in patients with CHD, manifested as lower relative frontal perfusion and higher relative hippocampal perfusion as compared to controls (p=0.014 and p=0.020).

In a subgroup analysis of CHD patients only, we found significantly lower whole brain (p=0.044) and frontal perfusion (p=0.035) in patients with systemic-to-pulmonary shunt as compared to patients without.

Discussion

As in healthy neonates, cerebral perfusion in CHD patients increases with age. This neonatal increase of cerebral perfusion is well-described in healthy children and discussed to represent high metabolic activity e.g. due to high energy consumption of oligodendrocytes for myelination6. Whereas whole brain perfusion was similar between the groups, localized changes and redistribution of regional perfusion in CHD confirm the influence of cardiac disease on cerebral blood supply. One causal factor may be the systemic-to-pulmonary shunt, a treatment needed in several types of severe CHD. This type of shunt (e.g. open arterial duct or modified Blalock-Taussig shunt) can lead to an unfavorable disbalance of systemic to pulmonary perfusion7 by the “shunt steal effect” with diastolic flow decrease or even run-off of arterial blood (in arteries providing brain and other systemic organs) into the pulmonary circulation8. With the decreased frontal and whole brain perfusion in patients with shunt detected in this study, we found evidence that this shunt steal effect significantly affects cerebral perfusion.Conclusion

Whole brain cerebral perfusion is decreased in CHD patients with systemic-to-pulmonary shunts. However, further investigation is needed to study effects of altered perfusion on brain maturation, growth and neurodevelopmental outcome.Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF 320030_184932) and Mäxi Foundation.References

1. Mebius

MJ, Kooi EMW, Hard CM, Bos AF. Brain Injury and Neurodevelopmental Outcome in

Congenital Heart Disease: A Systematic Review. PEDIATRICS. 2017;140(1).

2. Feldmann M,

Ullrich C, Bataillard C, et al. Neurocognitive outcome of school-aged children

with congenital heart disease who underwent cardiopulmonary bypass surgery: a

systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):236.

3. Nagaraj UD,

Evangelou IE, Donofrio MT, et al. Impaired Global and Regional Cerebral

Perfusion in Newborns with Complex Congenital Heart Disease. Journal of

Pediatrics. 2015.

4. Lu H, Clingman C,

Golay X, van Zijl PC. Determining the longitudinal relaxation time (T1) of

blood at 3.0 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52(3):679-682.

5. Tzourio-Mazoyer N,

Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of

activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI

single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15(1):273-289.

6. Biagi L,

Abbruzzese A, Bianchi MC, Alsop DC, Del Guerra A, Tosetti M. Age dependence of

cerebral perfusion assessed by magnetic resonance continuous arterial spin

labeling. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25(4):696-702.

7. Day RW, Tani LY,

Minich LL, et al. Congenital heart disease with ductal-dependent systemic

perfusion: Doppler ultrasonography flow velocities are altered by changes in

the fraction of inspired oxygen. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation

: the official publication of the International Society for Heart

Transplantation. 1995;14(4):718-725.

8. Kim EH, Lee JH,

Song IK, et al. Potential Role of Transfontanelle Ultrasound for Infants

Undergoing Modified Blalock-Taussig Shunt. Journal of Cardiothoracic and

Vascular Anesthesia. 2018;32(4):1648-1654.

Figures