2345

Integration of imaging measurements at micro-, meso and macro-scale of the caudal medulla on a postmortem infant subject1MGH, Boston, MA, United States, 2BCH, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neonatal, Multimodal, postmortem, brain development

The core lesion of SIDS is a set of medullar nuclei with abnormalities correlated with sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). We performed ex vivo whole brain and brainstem MRI, optical coherence tomography and histology at an unprecedented spatial resolution on a postmortem infant brain to investigate the structural properties of the caudal medulla. In our image processing pipeline, we register all image modalities into the same coordinate system along with a rich set of segmentation labels. Such multimodal construction helps us validate imaging findings at various resolution levels and will serve as prior information in automated segmentation solutions.

Introduction

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is the leading cause of postneonatal infant mortality in industrialized nations, with a rate of 0.39/1000 live births in the United States alone. Even though certain environmental factors increase the risk of SIDS, a subset of SIDS may be the result of an intrinsic defect in brain anatomy, in particular of the subcortical ascending arousal network (AAN) [1]. Arousal pathways of the AAN originate in the brainstem and activate awareness networks in the central cortex via synapses in the hypothalamus, thalamus, basal forebrain, or, alternatively via direct innervation of the cerebral cortex itself. We also believe that a set of mostly serotonergic nuclei with abnormalities, which we call the core lesion, is correlated with SIDS. To study SIDS pathology, we need to be able to image the brain from neurons, via histology, to 3D connectivity, via diffusion MRI. Here we present our integrated postmortem imaging pipeline from macro- to micro-scale.Imaging Modalities

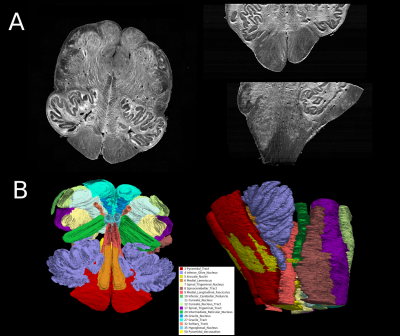

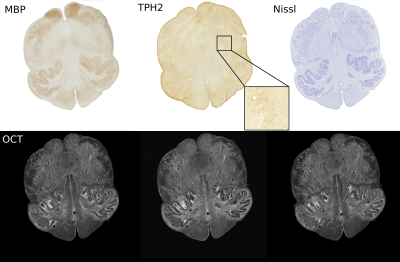

Our subject is a 7-month-old male, born full-term after 40 weeks gestation via Cesarian section. The cause of death was established to be SIDS according to recently updated standardized guidelines [2]. After extraction [3], the whole brain was fixed for 42 days before imaging in fomblin. For the macroscale imaging, we used ex vivo structural MRI imaging of the whole brain and the excised brainstem on a 3 T Siemens TIM Trio at the following isotropic resolutions: 550 µm and 250 µm, respectively, and diffusion MRI with 90 directions at 700 µm. For the mesoscale imaging, we further blocked the brainstem and isolated the caudal medulla to perform volumetric Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) [4]. Every blockface imaging covers the top first 150 µm of tissue. A vibratome is coupled to our imaging system to section 2 50-µm thick slices of tissue before imaging deeper in the tissue. Because the imaging is performed prior to the sectioning, the tissue remains undistorted, and each physical slice that is being used for histology has a corresponding optical slice. The optical scattering of tissue was then calculated, and the OCT volume reconstructed at 10 µm isotropic (Figure 2A). Figure 1 shows the imaging data of the caudal medulla from the whole brain structural MRI at 550 µm (A), the brainstem MRI at 250 µm (B), and the optical scattering coefficient calculated from the OCT imaging at 10 µm (C). For the micro-scale, we performed histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC) on the slices obtained during the OCT imaging. The slices are divided into four series, three of them being stained for Nissl (health neurons), Myelin Basic Protein (MBP), TPH2 (serotonergic neurons), and the fourth one is kept in reserve.Image Analysis

The OCT volume was segmented for nuclei and tracts following the Paxinos atlas [5]. To reduce manual labor, we used SmartInterpol [6], an algorithm developed to automatically segment unlabeled slices across a volume using Deep Learning and Multi Atlas Segmentation (MAS), allowing the segmentor to only label every fifth slice. Figure 2B shows the results of SmartInterpol after manual segmentation of the OCT volume shown in Figure 2A. All the modalities are registered into the same coordinate system. First, the MRI dataset and OCT volumes are registered in the whole brain space as shown in Figure 1D. The brainstem MRI data is shown with the heatmap and the OCT volume in grayscale on top of it. Then the histology slices are registered to the OCT volume. Each slice has a corresponding OCT image which we use to 3D reconstruct histological volumes using non-linear registration [7] (due to high distortion in the histology process). The histology slices can be used for validating the segmentation but it will also be used for mapping out the location and density of the serotonergic neurons in the common space and the correlation with the core lesion and the connectivity. The segmentation will be transferred to the whole brain diffusion data, and the connectivity of the core lesion will be assessed.Conclusion

We have established a pipeline to image the infant brainstem. The presented study was carried out on a 7-month-old whose brain has mostly already myelinated, providing good contrast even for the MRI of the brainstem. However, for younger brains, where the myelination is not fully completed, the MRI contrast might prove to be suboptimal, while OCT will remain high on CNR. Therefore, our proposed pipeline will allow us to study the infant brain through the first year of life without the challenge of lacking sufficient imaging contrast. The OCT data acquisition of the infant brainstem and its segmentation is the first step in the creation of a high-resolution atlas of its nuclei, tracts and cranial nerves. These will also serve as a training set for the development of an automated segmentation tool for our imaging modalities, both for the OCT and MRI data sets. Our work lays the foundation to compare brainstem connectivity between SIDS cases and controls, with the potential to identify biomarkers and abnormalities of the disease not detectable by standard histopathological techniques.Acknowledgements

This project was made possible by in part by grant number 2019-198101 from the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, an advised fund of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, a grant from the American SIDS Institute, NIH NINDS 1R21NS106695, as well as NICHD 1R01HD102616-01A1 and 5R21HD095338-02, as well as NIA R01AG057672 and RF1AG072056. We would like to acknowledge Holly Freeman, Maitreyee Kulkarni, Nathan Ngo, Sam Blackman, Seoyoon Kim, Ream Gebrekidan, Emily M. Williams, Emma Rosenblum, Jessica Roy and Anja Sandholm for their assistance in preparing and imaging the postmortem tissue, carrying out histology experiments as well as for their expert manual segmentations.

References

[1] Edlow, B.L., et al., Neuroanatomic connectivity of the human ascending arousal system critical to consciousness and its disorders. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 2012. 71(6): p. 531-46.

[2] Goldstein, R., et al., Inconsistent classification of unexplained sudden deaths in infants and children hinders surveillance, prevention and research: recommendations from The 3rd International Congress on Sudden Infant and Child Death. Forensic Sci Med Pathol., 2019.

[3] Rutty, G. and J.L. Burton, The Hospital Autopsy: A Manual of Fundamental Autopsy Practice. Third Edition ed. 2010: Hodder Arnold Publication.

[4] Huang, D. et al. “Optical Coherence Tomography”, Science vol. 80, no. 254, pp.1178–1181, 1991.

[5] Paxinos G., Huang X.F., et al., “Organization of Brainstem Nuclei”, The Human Nervous System, pp. 260-327. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press, 2012

[6] Atzeni, Alessia, et al. A probabilistic model combining deep learning and multi-atlas segmentation for semi-automated labelling of histology. International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer, Cham, 2018.

[7] Iglesias, Juan Eugenio, et al. "Model-based refinement of nonlinear registrations in 3D histology reconstruction." International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer, Cham, 2018.

Figures

Figure 3: Registered histology and IHC slices: Myelin Basic Protein (fibers), TPH2 (serotonergic neurons), and Nissl (healthy neurons) and their corresponding sequential OCT. The zoomed-in insert for the TPH2 sample displays 2.25x2.25 mm2 size tissue patch.