2342

Feto-placental oxygenation and brain development in fetal growth restriction

Emily Peacock1, Paponrad Tontivuthikul2, Joanna Chappell1, Nada Mufti1,2, Janina Schellenberg2, Michael Ebner1, Sebastien Ourselin1,3, Anna David2,4,5, Rosalind Aughwane2, and Andrew Melbourne1,2,3

1School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Institute for Women's Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Department of Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 4University Hospital KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 55NIHR University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre, London, United Kingdom

1School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Institute for Women's Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Department of Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 4University Hospital KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 55NIHR University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, Brain, Fetus, Machine Learning

State-of-the-art machine learning algorithms were applied to create MRI 3D super-resolution reconstructions of fetal brains to analyse brain development in fetal growth restriction. Reconstructions were segmented into the grey matter, white matter, deep grey matter, cerebellum and brainstem, and volumetric and cortical surface data was extracted. We found that the five brain regions segmented were significantly smaller in the FGR cohort than in controls, and that this effect was linked to feto-placental blood oxygen saturation. FGR fetuses showed evidence of brain sparing from MRI and ultrasound measurements and preservation of tissue relationships, such as the grey:white matter ratio.Introduction

Poor placentation and spiral artery remodelling early in pregnancy results in placental insufficiency, where the placenta is unable to reach the oxygen and nutritional demands of a growing fetus. This is the principal cause of fetal growth restriction (FGR), defined by a Delphi consensus as estimated fetal weight (EFW) less than the 3rd centile, or less than the 10th centile with abnormal fetal or maternal Doppler’s 1. In FGR, the chronically hypoxic environment initiates an adaptive response where fetal blood flow is redistributed to vital organs 2,3. This results in asymmetric growth and a ‘brain sparing’ effect, but it fails to fully protect brain development 4. FGR infants demonstrate significantly poorer motor and cognitive ability at school age compared to normally grown age-matched controls, as well as having higher rates of memory and neuropsychological dysfunction. FGR is also a significant risk factor for cerebral palsy 5. MRI, ultrasound and postpartum studies found that infants who were FGR have decreased myelin content 6, grey matter 7, cortical cells 8 and connectivity 9,10.MRI’s excellent soft tissue visualisation enables segmentation of individual brain structures. Computational MRI models can estimate feto-placental blood Oxygen Saturation (fbO2). This work applies these techniques to investigate brain development in FGR.

Methods

All participants gave written, informed consent and the data was anonymised.18 FGR cases and 16 appropriately grown controls were included. MRI scans were performed under free breathing using a 1.5T Siemens Avanto scanner and a voxel resolution of 1x1x3.9mm. 2D T2-weighted HASTE MRI images in axial, coronal and sagittal planes were acquired.

State-of-the-art machine learning algorithms were applied to generate 3D super-resolution brain reconstructions (SRRs) 11. The algorithms consisted of slice-to-volume registration and outlier-robust SRR cycles. The SRRs were segmented into the grey matter (GM), white matter (WM), deep grey matter (DGM), cerebellum and brainstem. Volume and cortical surface area data were extracted. Additionally, total fetal body volumes were manually segmented to investigate brain sparing using ITK-SNAP 12.

The results were linked to published and validated feto-placental blood oxygen saturation (fbO2) data 13,14 estimated from combined diffusion and relaxation MRI (DECIDE)15 to investigate the effect of fbO2 on brain development.

To generate ultrasound measurements, EFW calculated using the Hadlock formula 16 was converted to total fetal volume using a density ratio of 1gram=1,000mm3. Total brain volume was calculated as head circumference(mm)3/6π2.

Statistical T-tests, Kursall-Wallis One-way Anova tests and Pearson’s correlation coefficient were used to analyse results.

Results

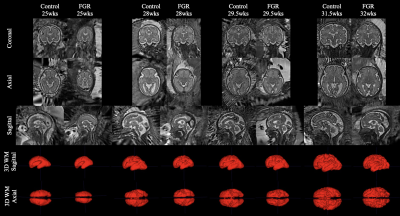

MRI Reconstruction14 control (gestational age (GA, weeks+days) 25+1-34+0; mean: 29+6) and 12 FGR (GA 24+4-32+0; mean: 27+5) (P=0.02)) brains were successfully reconstructed and segmented (Fig 1 & Fig 2). EFW was confirmed to be significantly higher in control vs FGR (mean±standard deviation 1482g±145g control vs 739g±297g FGR (P=0.0001)). At the time of the MRI scan 5 FGR cases had abnormal Uterine (Ut) and Umbilical Artery Dopplers, 3 had abnormal Ut. Dopplers and 4 had normal Dopplers.

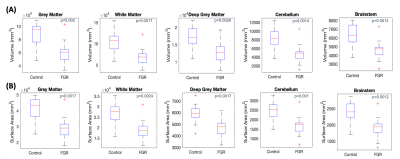

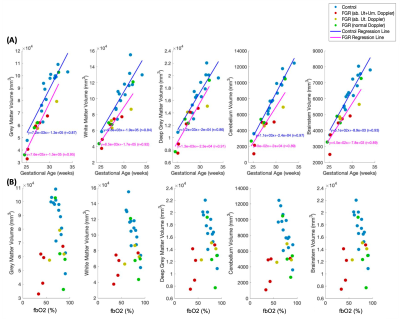

The volume and surface area were significantly lower in FGR than in controls for all brain structures (Fig 3 & Fig 5a). We did not observe a significant difference in GM:WM ratio in FGR compared to control (83.07%±7.49% control vs 86.69%±3.29% FGR, p=0.13) (Fig 4c).

Brain sparing

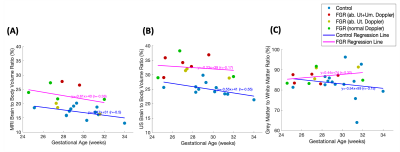

11 controls and 9 FGRs had successful full-body segmentations. Brain-to-body ratios were found to be higher in FGR than in controls using MRI (17±2% control vs 22±4% FGR, 95%CI: 2.6 – 8.3%, p <0.001) and also using ultrasound estimates (25±2% control vs 32±3% FGR, 95%CI 4.9 – 10.1%, p<0.001) (Fig 4a/b).

Fetal oxygen saturation

There was a strong negative correlation between fbO2 and brain volume in control cases (r=-0.83), falling to r=-0.41 after correcting for GA. FGRs with normal Dopplers followed this trend, whereas FGRs with abnormal uterine and umbilical Dopplers had both low brain volume and low fbO2 (Fig 5).

Discussion

Our results show the effects of hypoxia on brain development in FGR. We found brain volume and surface areas were lower in FGR than control, but that there was a significant brain sparing effect when normalised for fetal size with both MRI and ultrasound. We did not observe a difference between component parts of the brain, particularly the grey:white matter ratio. This suggests the brain sparing effect is preserving normal tissue relationships within our dataset. We also showed the effect of GA and feto-placental blood oxygen saturation on brain size, but our small cohort precludes making any firm conclusions about these relationships. Future work will build this cohort to further investigate the effect of oxygenation on fetal organ development in FGR. This could be useful in diagnosing the effect hypoxia is having on the developing brain and may aid parental counselling and complex clinical decision making.Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Wellcome Trust (210182/Z/18/Z and Wellcome Trust/EPSRC NS/A000027/1) and the Radiological Research Trust. The funders had no direction in the study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation or publication decision. We would like to thank Dr Magda Sokolska and Dr David Atkinson for their invaluable help and advice acquiring the imaging data for this study.References

1. Gordijn SJ, Beune IM, Thilaganathan B, et al. Consensus definition of fetal growth restriction: a Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. Sep 2016;48(3):333-339.2. Damodaram MS, Story L, Eixarch E, et al. Foetal volumetry using magnetic resonance imaging in intrauterine growth restriction. Early human development. 2012;88:S35-S40.

3. Poudel R, McMillen IC, Dunn SL, Zhang S, Morrison JL. Impact of chronic hypoxemia on blood flow to the brain, heart, and adrenal gland in the late-gestation IUGR sheep fetus. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2015;308(3):R151-R162.

4. Roza SJ, Steegers EA, Verburg BO, et al. What is spared by fetal brain-sparing? Fetal circulatory redistribution and behavioral problems in the general population. American journal of epidemiology. 2008;168(10):1145-1152.

5. Miller SL, Huppi PS, Mallard C. The consequences of fetal growth restriction on brain structure and neurodevelopmental outcome. The Journal of physiology. 2016;594(4):807-823.

6. Chase HP, Welch NN, Dabiere CS, Vasan N, Butterfield LJ. Alterations in human brain biochemistry following intrauterine growth retardation. Pediatrics. 1972;50(3):403-411.

7. Tolsa CB, Zimine S, Warfield SK, et al. Early alteration of structural and functional brain development in premature infants born with intrauterine growth restriction. Pediatric research. 2004;56(1):132-138.

8. Samuelsen GB, Pakkenberg B, Bogdanović N, et al. Severe cell reduction in the future brain cortex in human growth–restricted fetuses and infants. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2007;197(1):56. e51-56. e57.

9. Batalle D, Eixarch E, Figueras F, et al. Altered small-world topology of structural brain networks in infants with intrauterine growth restriction and its association with later neurodevelopmental outcome. Neuroimage. Apr 2 2012;60(2):1352-1366.

10. Padilla N, Fransson P, Donaire A, et al. Intrinsic functional connectivity in preterm infants with fetal growth restriction evaluated at 12 months corrected age. Cerebral Cortex. 2017;27(10):4750-4758.

11. Ebner M, Wang G, Li W, et al. An automated framework for localization, segmentation and super-resolution reconstruction of fetal brain MRI. NeuroImage. 2020;206:116324.

12. Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage. Jul 1 2006;31(3):1116-1128.

13. Aughwane R, Mufti N, Flouri D, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging measurement of placental perfusion and oxygen saturation in early‐onset fetal growth restriction. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2021;128(2):337-345.

14. Flouri D, Darby JR, Holman SL, et al. Placental MRI Predicts Fetal Oxygenation and Growth Rates in Sheep and Human Pregnancy. Advanced Science. 2022;9(30):2203738.

15. Melbourne A, Aughwane R, Sokolska M, et al. Separating fetal and maternal placenta circulations using multiparametric MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2019;81(1):350-361.

16. Hadlock FP, Harrist R, Sharman RS, Deter RL, Park SK. Estimation of fetal weight with the use of head, body, and femur measurements—a prospective study. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1985;151(3):333-337.

Figures

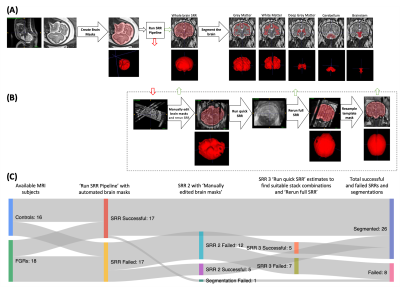

Fig. 1: A visual illustration of the MRI super-resolution reconstruction (SRR) process. (A) The ideal SRR pipeline. (B) Additional steps to try to create a SRR from the subject. Red arrows represent the stage the ideal workflow fails, green arrows represent stages that SRRs might become successful and return to the workflow above. (C) A Sankey diagram showing the number of successful or failed subjects at each SRR round; each round corresponds to a SRR stage in (A) or (B).

Fig. 2: 3D Super-resolution brain reconstructions of control and FGR fetuses at 4 representative time frames (25, 28, 29.5 and 31.5 weeks). Axial, coronal and sagittal views of the SRRs have been shown at each time frame, as well as sagittal and coronal views of the 3D white matter segmentation.

Fig. 3: Statistically significant differences in the cerebral parameters of brain structures between control and FGR cohorts. Kruskal-Wallis One-way ANOVA results display statistically significant differences between all five brain structures for volume (mm3) (A) and surface area (mm2) (B) at a 1% significance level.

Fig. 4: The ratio of total brain to body volume found by MRI (A) versus ultrasound (B) and the ratio of Grey Matter to White Matter found by MRI (C).

Fig. 5: Brain structure volumes linked to gestational age (weeks) (A) and feto-placental blood Oxygen Saturation (fbO2, %) (B).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/2342