2341

High Flip Angle Chemical-Shift Encoded MRI for Imaging Fetal Adipose Tissue1Medical Biophysics, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada, 2Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada, 3Maternal, Fetal and Newborn Health, Children's Health Research Institute, London, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Fetal, Fat

Fat fractions in fetal adipose tissue vary across gestation and across different regions of the body, and can be measured by chemical shift encoded MRI which provides accurate measurements of fat fraction above 10%. The assessment of lower fat fractions can be improved by increasing flip angle, but this introduces T1 bias. We demonstrated that this T1 bias can be corrected using fetal adipose tissue water and lipid T1 values, preserving accuracy of the fat fraction measurement while simultaneously improving its precision in fetal adipose tissue.

Introduction

Adipose tissue is an essential organ and has critical roles in the newborn as both an energy reservoir and a heat producer1. During fetal development, adipose cells fill with lipids and fat fraction values vary from very low (less than 10%) to high (greater than 80%)2; even within a normal fetus depending on the location of the measurement3. Low fat fractions are expected early in adipose development (second trimester)2 and in brown adipose tissue3.Low flip angles are commonly used to minimize bias in proton density fat fraction (PDFF) measurements4; however, to measure low PDFF with chemical shift encoded (CSE) MRI, we need to increase the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which can be achieved by acquiring the images with a higher flip angle4. This introduces T1 bias, resulting in an overestimation of the PDFF4, highest when the value is around 50%. The trade-off for the ability to measure lower PDFFs is a variable overestimation of PDFF, and to correctly measure the PDFF in all fetal tissues, the T1 bias must be corrected.

Previous work has shown that it is possible to correct the T1 bias by correcting the signal with a known T1 value4,5 and has been performed in phantoms and adult vertebrae4,5. We applied this methodology to fetal adipose tissue where the lipid and water T1s potentially change with gestational age6, and fat fractions vary from very low to very high values.

Methods

Volunteers with singleton pregnancies and gestational ages (GA) between 28 and 38 weeks were imaged in a wide bore (70 cm) 1.5T MRI (GE MR450w). During an approximately 30 min MRI exam, two 3D CSE-MRI acquisitions (specific implementation: Quantitative IDEAL, TR 9.7-12.7 ms, Field of View 50 cm, 160×160 pixels, slice thickness 4-6.5 mm, 42-78 slices, ARC acceleration 2x phase 2.5x slice and 32x32 calibration lines, acquisition time 12-24 s) with a low flip angle (6°, LFA) or a high flip angle (20°, HFA) were used to image fetal adipose tissue during a maternal breath hold. A spherical ROI (diameter 10mm) was placed in the adipose tissue of the fetal cheek in both the LFA and HFA images (3D Slicer v4.11.0-2019-11-11). The PDFF was calculated from the mean lipid and water signals. The standard deviation of the PDFF in the ROI was used to estimate precision and compared between LFA and HFA images using a Wilcoxon matched-pairs test (GraphPad v9.4.1).DESPOT17 was used to calculate the lipid and water T1s, and a linear regression was performed between the T1 values and GA (GraphPad v9.4.1). The regression lines were used to estimate a GA-dependent T1 for lipid and water, and these values were used to correct the lipid and water signals and calculate corrected fat fractions. Additionally, published fetal adipose tissue T1 values of 946.6 ms for water and 224.9 ms for lipid6 were used to correct the lipid and water signals and corrected PDFF was calculated for both the LFA and HFA images. The PDFF was compared between LFA and HFA measurements using a Bland-Altman analysis (GraphPad v9.4.1) before and after T1 correction and the bias and 95% confidence intervals were determined.

Results

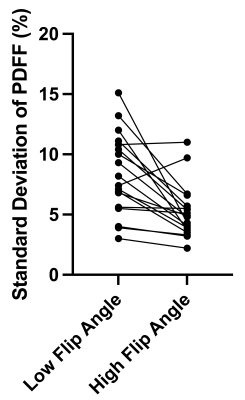

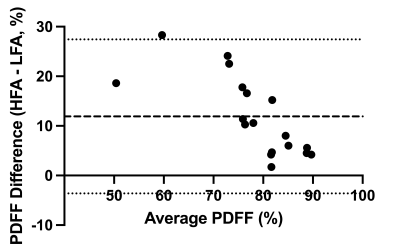

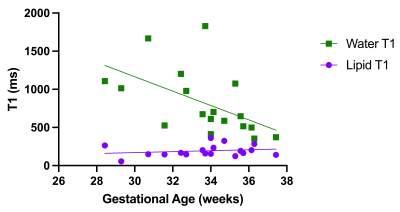

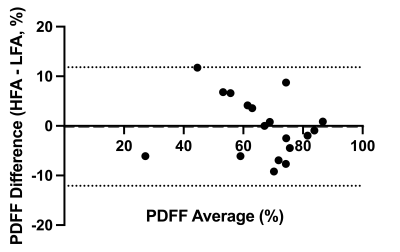

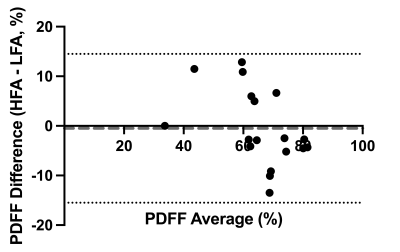

18 pregnant volunteers participated in this study with BMI ranging from 18 – 43.2 kg/m2. The PDFF standard deviations between LFA and HFA images were significantly different (P=0.0003) (Figure 1).The bias between uncorrected LFA PDFF and HFA PDFF was 12% (-3.6% to 27%) (Figure 2). The lipid T1 did not vary significantly with GA (P=0.4), while the water T1 significantly decreased with GA (P=0.02) (Figure 3). After correcting both the LFA and HFA PDFFs with GA-dependent T1 values, the bias was –0.13% (-12% to 12%) (Figure 4). After correcting both the LFA and HFA PDFFs with published T1 values, the bias was -0.49% (-15% to 14%) (Figure 5).

Discussion

The standard deviation was lower in the HFA PDFF images than in the LFA PDFF images, indicating improved precision when using an HFA. In cases where the standard deviation went up in the HFA PDFF compared to LFA PDFF, we hypothesize that biological variation within the adipose tissue depot dominated the noise in the measurement.The bias between HFA and LFA fetal PDFF measurements was reduced to nearly zero after T1 correction. The bias was only slightly smaller when using GA-dependent T1 values (-0.13%) compared to average published T1 values (-0.49%), consistent with previous work5. This work showed that some error in T1 value can be tolerated without a significant decrease in accuracy, which is consistent with our results.

Conclusion

By using an HFA with CSE-MRI, it was possible to improve precision without sacrificing accuracy. This will be important for imaging fetal adipose tissue, especially for studies looking at lower fat fractions. These low-PDFF measurements will be critical to understanding early adipose tissue development as well as brown adipose tissue development, which may give early indications of abnormal metabolic programming.Acknowledgements

Grant support from the Children’s Health Research Institute, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research and General Electric.References

1. Desoye G & Herrera E. Adipose tissue development and lipid metabolism in the human fetus: The 2020 perspective focusing on maternal diabetes and obesity. Prog Lipid Res. 2021;81:101082.

2. Giza SA, Olmstead C, McCooeye DA, et al. Measuring fetal adipose tissue using 3D water-fat magnetic resonance imaging: a feasibility study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(5):831-837.

3. Giza SA, Koreman TL, Sethi S, et al. Water-fat magnetic resonance imaging of adipose tissue compartments in the normal third trimester fetus. Pediatr Radiol. 2021;51(7):1214-1222.

4. Liu CY, McKenzie CA, Yu H, et al. Fat quantification with IDEAL gradient echo imaging: correction of bias from T(1) and noise. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(2):354-364.

5. Yang IY, Cui Y, Wiens CN, et al. Fat fraction bias correction using T1 estimates and flip angle mapping. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;39(1):217-223.

6. Sethi S, Giza SA, Goldberg E, et al. Quantification of 1.5T T1 and T2* Relaxation Times of Fetal Tissues in Uncomplicated Pregnancies. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2021;54(1):113-121.

7. Deoni SCL, Rutt BK & Peters TM. Rapid combined T1 and T2 mapping using gradient recalled acquisition in the steady state. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49(3):515-526.

Figures

Figure 1: Comparison of proton density fat fraction standard deviation between low flip angle and high flip angle images. The proton density fat fraction standard deviations were significantly different (P=0.0003). The high flip angle standard deviations were lower in most cases; however, they were similar in a few cases and went up in another. This is likely due to biological variation dominating the measurement noise.

Figure 2: Bland-Altman of uncorrected high flip angle – low flip angle proton density fat fraction. A comparison of uncorrected high flip angle proton density fat fraction against uncorrected low flip angle proton density fat fraction gave a bias of 12% (-3.6% to 27%).

Figure 3: Lipid and water T1s vs. gestational age. The lipid T1 did not change as a function of gestational age (P=0.4), while the water T1 decreased as a function of gestational age (P=0.02).

Figure 4: Bland-Altman of gestational age-dependent T1 corrected high flip angle – low flip angle proton density fat fraction. After correcting the proton density fat fraction with gestational age-dependent T1 values, a comparison of high flip angle proton density fat fraction against low flip angle proton density fat fraction had a bias of –0.13% (-12% to 12%).

Figure 5: Bland-Altman of published T1 corrected high flip angle – low flip angle proton density fat fraction. The proton density fat fraction measurements were corrected with published values for fetal adipose tissue lipid and water T1s. Then a comparison of the corrected high flip angle proton density fat fraction against the corrected low flip angle proton density fat fraction had a bias of –0.49% (-15% to 14 %).