2336

Exploring the effect of elevated maternal BMI on image quality in fetal MRI

Kathleen Elizabeth Colford1, Daniel Cromb1, Zoe Hesketh1, Tom Finck1,2, Ayse Ceren-Tanritanir1,3, Serena Counsell1, and Mary Rutherford1,4

1Centre for the Developing Brain, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, Kings College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Neuroradiology, Klinikum rechts der Isar der Technischen Universität München, Munich, Germany, 3Guys and St. Thomas’s NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom, 4MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom

1Centre for the Developing Brain, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, Kings College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Neuroradiology, Klinikum rechts der Isar der Technischen Universität München, Munich, Germany, 3Guys and St. Thomas’s NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom, 4MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Fetal, Data Analysis, Maternal BMI, Signal to Noise Ratio

We assessed SNR (signal-to-noise-ratio) against elevated maternal BMI in fetal brain/body MRI imaging to examine if SNR decreases both objectively/subjectively, and if MRI could be an alternative imaging modality in prenatal care. Spearman’s Correlation-Rank coefficient was used to identify relationships between SNR measurements in ROI’s and maternal BMI. There’s a negative downward trend between maternal BMI and SNR seen for all fetal ROIs (particularly in regions more susceptible to SNR); subjective assessment didn’t identify any association between BMI and image quality. Our results suggest that MRI is a viable alternative to ultrasound in pregnant women with elevated BMI.Background

The use of ultrasound in prenatal care can be challenging when maternal body mass index (BMI) is significantly elevated [1–3]. A higher maternal BMI is also associated with increased fetal anomalies, with cardiac and craniofacial abnormalities not only being more common, but more difficult to visualise with women with BMI over 30 [4].Around 20% of the UK population are obese, and antenatal imaging is performed using ultrasound. Consequently, there are many pregnant women who may not be experiencing optimal antenatal imaging [5]. Fetal MRI is a safe, non-invasive imaging modality that is now readily available, with improved image acquisition protocols resulting in quicker scanning times. Advanced motion-correction and image reconstruction algorithms, along with excellent tissue contrast of the fetal brain/body, means that MRI can provide superior visualisation of anatomical structures, aiding clinicians with diagnosis in a variety of conditions.

We aimed to explore how MR image quality may be affected by maternal BMI, using both objective and qualitative measures.

Methods

All participants were referred to our hospital for a clinical fetal MRI in 2021, with signed informed, written consent to clinical information and MR images being used for research (NHS REC: 07/H0707/105). Women with a BMI>35 at the time of their fetal MRI scan were identified. Women with a matched gestational age and BMI<30 were selected as a matched ‘control’ cohort. All subjects were scanned on a 1.5T Philips Ingenia MRI scanner in either supine or supported left lateral position, using dStream anterior and posterior in-built coils. Maternal comfort was maximised by elevating the head and legs and continuous monitoring of vital signs, with verbal interactions, were performed throughout.Fetal images were acquired using a T2-weighted single-shot fast-spin-echo sequence (TR=1500ms, TE=80ms/180ms, voxel size=1.25×1.25×2.5/1.5x1.5x2.5mm, slice thickness=2.5mm, slice spacing=1.25mm), optimised for fetal imaging.

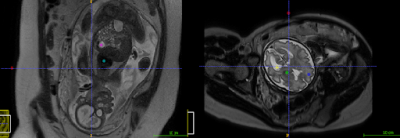

Spherical 5mm3 regions of interest (ROIs) were placed in the background from the MRI acquired fetal brain and body images using ITK-Snap [6] to obtain mean and standard-deviation values of the background MR signal. Three ‘fetal brain’ and two ‘fetal body’ ROI’s were placed (see Figure 1). These regions were chosen as they represent areas with a wide-range of T2-weighted MR signal. Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) was then calculated for each region using Equation 1, as previously published [7], allowing an objective measure of SNR for each ROI to be calculated

Equation 1: Signal to noise ratio (SNR)= MeanROI /SDBG

Where MeanROI is the mean signal from ROIs and SDBG is the signal standard deviation from the image background.

Fetal brain image reconstruction and review:

The acquired fetal brain data were motion-corrected and reconstructed into 3-Dimensional volumes with an isotropic 0.8mm3 resolution using an advanced slice-to-volume (SVR) reconstruction technique [8,9,10]

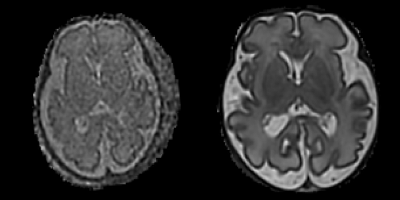

Two experienced fetal radiologists performed grading of these SVRs, with tight masking of the brain enabling blinding to maternal BMI. Images were scored according to image noise, anatomical clarity and clinical interpretability. For each category, a score of 1 to 3 was assigned, representing poor, average or excellent SNR, clarity or interpretability respectively (Figure 22). These scores were then summed to produce an overall “Radiologist” score, providing a qualitative measurement of image quality

Statistical Analysis

Spearman’s Correlation Rank coefficient was used to identify relationships between SNR measurements in each ROI and maternal BMI, using Stats Models v0.13.5 in Python. P-values were corrected for multiple-testing; corrected p-values <0.05 were considered significant.

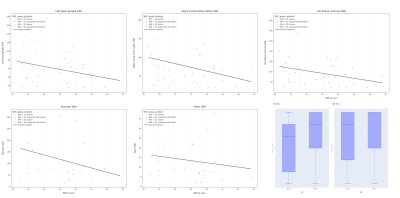

Results

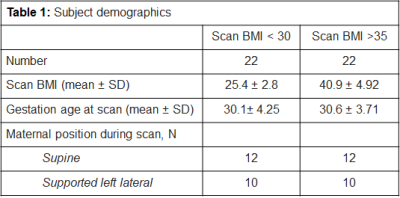

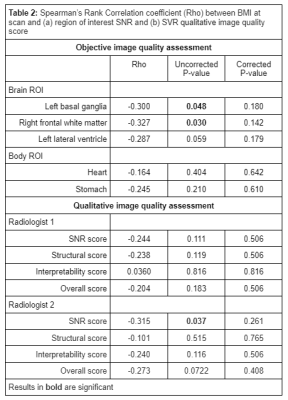

Demographics for all participants can be seen in Table 1. Results for the association between maternal BMI at the time of the scan and (a) ROI SNR and (b) subjective image quality scores can be seen in Table 2.Whilst there was a significant negative correlation between maternal BMI and SNR in the LBG (Rho=-0.3, p=0.048) and the RFWM (Rho=-0.327, p=0.03) of the fetal brain images, these associations didn’t survive multiple-testing correction. The SNR score from one radiologist showed a significant negative correlation with maternal BMI (Rho=-3.15, p=0.037), but again, this didn’t survive multiple-testing correction. Overall SVR score seen in Figure 3.

Discussion

There is a negative trend between maternal BMI and SNR seen for all fetal ROIs. This association was strongest in regions that have lower T2 signal and therefore, more susceptible to poor SNR. However, when motion-corrected and reconstructed 3D brain volumes were qualitatively assessed there was no association between BMI and image quality.BMI was used as a proxy for increased distance from the receiver coils to image isocenter, but other factors also affect SNR, e.g. amniotic fluid volume, the shape of the maternal girth and fetal position. This should be explored in future work.

We only studied the effect of BMI on T2-weighted images and the effect of maternal BMI on other types of MR images require further assessment. Our results suggest that MRI with SVR is a viable alternative to ultrasound in pregnant women when ultrasound may be technically challenging, such as significantly elevated BMI.

Reliable delineation of brain structures and rapid scan sequences means MRI offers a suitable imaging modality for identifying structural fetal abnormalities [10]. The increased cost for MRI over ultrasound is a consideration, but selecting patients where ultrasound has been suboptimal or inconclusive may mitigate this.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by core funding from the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering [WT203148/Z/16/Z] and by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London and/or the NIHR Clinical Research Facility. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.References

1. Dashe JS, McIntire DD, Twickler DM. Maternal obesity limits the ultrasound evaluation of fetal anatomy. J Ultrasound Med Off J Am Inst Ultrasound Med 2009;28:1025–30.2. Khoury FR, Ehrenberg HM, Mercer BM. The impact of maternal obesity on satisfactory detailed anatomic ultrasound image acquisition. J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med Off J Eur Assoc Perinat Med Fed Asia Ocean Perinat Soc Int Soc Perinat Obstet 2009;22:337–41.

3. Tsai P-JS, Loichinger M, Zalud I. Obesity and the challenges of ultrasound fetal abnormality diagnosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2015;29:320–7.

4. Wolfe HM, Sokol RJ, Martier SM et al. Maternal obesity: a potential source of error in sonographic prenatal diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol 1990;76:339–42.

5. Ziauddeen N, Huang JY, Taylor E et al. Interpregnancy weight gain and childhood obesity: analysis of a UK population-based cohort. Int J Obes 2005 2022;46:211–9.

6. Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. NeuroImage 2006;31:1116–28.

7. Magnotta VA, Friedman L. Measurement of Signal-to-Noise and Contrast-to-Noise in the fBIRN Multicenter Imaging Study. J Digit Imaging 2006;19:140–7.

8. Kuklisova-Murgasova M, Quaghebeur G, Rutherford MA et al. Reconstruction of fetal brain MRI with intensity matching and complete outlier removal. Med Image Anal 2012;16:1550–64.

9. Uus A, Grigorescu I, van Poppel M et al. 3D UNet with GAN Discriminator for Robust Localisation of the Fetal Brain and Trunk in MRI with Partial Coverage of the Fetal Body. Bioengineering, 2021.

10. SVRTK - slice to volume reconstruction toolkit. 2022.

11. Weisstanner C, Kasprian G, Gruber GM et al. MRI of the Fetal Brain. Clin Neuroradiol 2015;25 Suppl 2:189–96.

Figures

Figure 1: Fetal ROI’s for brain and body; background (red), Left Basal Ganglia (green), Right Frontal White Matter (blue), Left Lateral Ventricle (yellow), heart (turquoise) and stomach (pink).

Figure 2: Examples of slice-to-volume reconstructed axial fetal brain slices with (1) poor SNR (Left) and (2) Good SNR (Right)

Figure 3: Scatter plots comparing maternal BMI and SNR for multiple fetal brain and body regions of interest, and box plots comparing the overall brain SVR score from both radiologists from participants grouped according to whether their BMI was above 35 or below 30.

Table 1: Subject demographics

Table 2: Spearman’s Rank Correlation coefficient (Rho) between BMI at scan and (a) region of interest SNR and (b) SVR qualitative image quality score

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/2336