2329

Metabolic Alternations in Normal Appearing Brain in Brain Tumor Patients: Potential Mechanism of Chemo-Brain1Center for Clinical Spectroscopy, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women's Hospital / Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Tumors, Spectroscopy, chemotherapy, normal-appearing brain

Patients that undergo chemotherapy have been shown to develop cognitive dysfunction after treatment. Previous studies have shown changes in white matter metabolism; however, few have examined grey matter metabolism. Our results show that glutamate, glutathione, creatine, N-acetylaspartate, and myoinositol were reduced in the posterior cingulate in tumor patients that underwent chemotherapy when compared to healthy controls. The effect of radiotherapy was also examined but did not show metabolic differences.Introduction:

The link between chemotherapy and radiation’s neurotoxicity on the brain is well-established. Radiation to the cranium, a standard treatment for patients with brain tumors, has been associated with significant cognitive dysfunction1 in 50-90% of patients. Other studies2,3,4 indicate grey matter atrophy, and ‘chemo’ brain in patients' post-chemotherapy. ‘Chemo’ brain is caused by the neurotoxic effects of chemotherapy disrupting attention and memory mechanisms. Identification of chemo brain is currently based on subjective patient reports; therefore, it is important to find qualitative and non-invasive methods of evaluating patients’ neurological states to augment post-chemotherapy.Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) is an analytical technique used to non-invasively investigate and provide information on the chemical composition of tissue in-vivo. MRS studies use contralateral voxels as a comparative negative control for metabolite concentrations in the tumor voxel. However, little is known about non-tumor tissue in tumor patients as it is assumed to be normal healthy brain tissue. This study differs from previous MRS studies by focusing on a location independent of tumor location and for which there are numerous studies of its normative concentration, namely, the posterior cingulate gyrus (PCG). Current literature1,5,6 focuses on the effects of radiation on white matter or fixates on only a few grey-matter metabolites. We hypothesize that the metabolite concentrations of tissue in tumor patients will differ from tissue in healthy controls.

Methods:

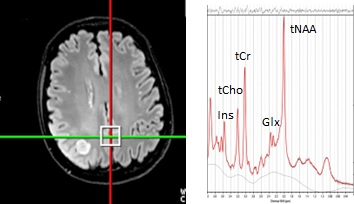

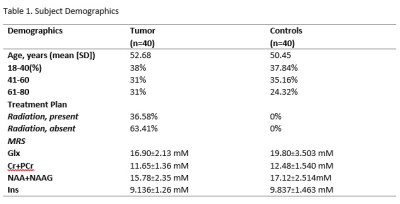

Data Collection: 80 MRS scans were acquired at 3T (Siemens Skyra) using point-resolved spectroscopy (TE=30ms) in 40 tumor patients and 40 control patients. The patients were age-matched to account for age-related changes in metabolites (Table 1) All scans were of high quality based on FWHM values (<15 Hz). In the second stage of the study, we extracted medical records to determine that 14 patients of the 30 patients underwent radiation in their standard-of-care treatment plan and compared them to 26 scans of patients that did not.Data processing and quantification: The MRS data were then reconstructed by OpenMRS lab and LCmodel to quantify the following metabolites: total creatine (tCr:Cr+Pcr), myoinositol (Ins), lactate (Lac), glutamate and glutamine (Glx), glutathione (GSH), total n-acetyl aspartate (tNAA: NAA+NAAG), total choline (tCho: GPC+Pch), lipids (MM14+Lip13a, MM09+Lip09, and MM20+Lip20). Through the exploratory statistical analysis via a paired t-test, we extracted significant metabolite differences in the PCG between the tumor patients and controls. A secondary analysis of tumor patients that did and did not receive radiation used a Mann-Whitney Test (due to non-parametric distribution) to analyze potential metabolite differences. Additionally, we conducted a linear regression for radiation patients mapping the metabolite differences between the time of radiation and the acquisition of the metabolite concentrations. We examined trends in tCr, Ins, Lac, Glx, tNAA, and lipids.

Results and Discussion:

We detected significantly lower concentrations of Glx, GSH, tCr, tNAA, and Ins, in the PCG in patients with brain tumors (Fig.2) when compared to healthy controls. This demonstrates that the non-tumor tissue in brain cancer patients is not metabolically normal. Thus, it cannot be assumed that the contralateral voxel will contain normal brain metabolite concentrations. Neuro-oncology studies1-6,10 conducted on non-tumor tissue typically observe the effects of therapies on brain tissue. Glx is involved in crucial excitotoxicity and neurotransmission pathways conducive to energy formation, survival, and growth. Glutamate that is released in the synaptic cleft is essential for the synaptic function to regulate memory function and normal cognitive function. Reduced glutamate7,8 has been found in cognitively impaired individuals. tNAA, an internal neuronal marker, can provide insight into grey matter volume and atrophy. Reduced tNAA is indicative of neuronal loss and is found in both post-chemotherapy and post-radiation treatment2,9,10. Reduced tNAA is linked to cognitive dysfunction. Cr resynthesizes ATP, thus playing an essential role in energy metabolism and homeostasis. One study hypothesized that reduced creatine can be indicative of post-treatment fatigue2. However, reduced Ins is not indicative of treatment-related changes. In fact, Ins, a glial marker, has been shown to increase post-chemotherapy treatment2. This raises the question of whether metabolite alteration is caused by something other than treatment neurotoxicity. Thus, to localize the potential reasons for metabolite variations, we explored the effects of proton radiation therapy in non-tumor tissue. There were no significant metabolite differences (p-value>0.05) between radiation patients and controls (Fig.3A). In the simple linear regression, no significant differences in the metabolites were found.Conclusion:

This study evaluated the assumption of normalcy extended to non-tumor tissue in tumor patients. We found significant metabolite differences between non-tumor tissue in tumor patients and non-tumor tissue in healthy controls. Results found in this study raise further questions on whether the alteration of metabolites can be wholly attributed to treatment neurotoxicity or perhaps another underlying mechanism is at play.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Center for Neuro-Oncology and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital radiology staff for their contributions to patient care.References

1. Makale, M. T., McDonald, C. R., Hattangadi-Gluth, J. A., & Kesari, S. (2017). Mechanisms of radiotherapy-associated cognitive disability in patients with brain tumours. Nature Reviews Neurology, 13(1), 52-64

2. Koppelmans, V., de Ruiter, M. B., van der Lijn, F., Boogerd, W., Seynaeve, C., van der Lugt, A., ... & Schagen, S. B. (2012). Global and focal brain volume in long-term breast cancer survivors exposed to adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast cancer research and treatment, 132(3), 1099-1106.

3. Kesler, S. R., Watson, C., Koovakkattu, D., Lee, C., O’Hara, R., Mahaffey, M. L., & Wefel, J. S. (2013). Elevated prefrontal myo-inositol and choline following breast cancer chemotherapy. Brain imaging and behavior, 7(4), 501-510

4. Pendergrass, J. C., Targum, S. D., & Harrison, J. E. (2018). Cognitive impairment associated with cancer: a brief review. Innovations in clinical neuroscience

5. Rutkowski, T., Tarnawski, R., Sokol, M., & Maciejewski, B. (2003). 1H-MR spectroscopy of normal brain tissue before and after postoperative radiotherapy because of primary brain tumors. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics, 56(5), 1381-1389

6. Sokół, M., Michnik, A., & Wydmański, J. (2006). Long-term normal-appearing brain tissue monitoring after irradiation using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in vivo: statistical analysis of a large group of patients. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics, 66(3), 825-832.

7. Hensley, C. T., Wasti, A. T., & DeBerardinis, R. J. (2013). Glutamine and cancer: cell biology, physiology, and clinical opportunities. The Journal of clinical investigation, 123(9), 3678-3684

8. Zeydan, B., & Kantarci, K. (2021). Decreased glutamine and glutamate: an early biomarker of neurodegeneration. International psychogeriatrics, 33(1), 1-2.

9. Horská, A., & Barker, P. B. (2010). Imaging of brain tumors: MR spectroscopy and metabolic imaging. Neuroimaging Clinics, 20(3), 293-310

10. Usenius, T., Usenius, J. P., Tenhunen, M., Vainio, P., Johansson, R., Soimakallio, S., & Kauppinen, R. (1995). Radiation-induced changes in human brain metabolites as studied by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy in vivo. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics, 33(3), 719-724.

Figures