2310

Assessing Ranges of Cerebral Blood Flow Velocity and Vessel Area with Phase Contrast in Children and Adults

Eamon Doyle1,2, Hannah Wiseman3, Isabel Torres3, Payal Shah4, John Wood2,5, and Matthew Borzage2,6

1Radiology, Children's Hospital of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 2Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 3Children's Hospital of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 4Children's Hospital of Los Angeles, Los, CA, United States, 5Division of Cardiology, Children's Hospital of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 6Pediatrics, Children's Hospital of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

1Radiology, Children's Hospital of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 2Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 3Children's Hospital of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 4Children's Hospital of Los Angeles, Los, CA, United States, 5Division of Cardiology, Children's Hospital of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 6Pediatrics, Children's Hospital of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Blood vessels, Blood, flow

Measuring brain blood flow is possible with phase contrast (PC) imaging. We assessed blood flow through and area of internal carotid and vertebral arteries in pediatric and adult populations. Sequences parameters are suggested based upon the findings to facilitate PC acquisitions at other institutions.Introduction

In this work, we assessed peak blood velocity and vessel size of the internal carotid (ICA) and vertebral arteries (VA) in pediatric patients, compared to adult volunteers, and used our results to select phase contrast (PC) MR sequence parameters and measure cerebral blood flow in children.The brain requires a significant fraction of the metabolic support of the body, and it lacks the capacity to buffer disruptions in blood supply. Thus, adequate cerebral blood flow (CBF) is vital to brain health1 and CBF measurements span many areas of brain research. CBF varies markedly with brain development throughout infancy, childhood, and senescence2-4. Altered CBF is associated with cardiovascular risk,5-6 small vessel disease,7 Alzheimer’s dementia,8 white matter lesions,9 anemia,10 stroke risk in sickle cell disease,11-12 and higher risk of non-cardiovascular mortality in the elderly13. CBF is a predictive biomarker for patients with severe depression,14 and CBF is modulated by pharmacological agents including substances of abuse,15 alcohol,16 and anesthetics4.

PC MR encodes flow by imparting phase to flowing spins proportional to their velocity. Thus, PC MR is a noninvasive approach which is well-suited to measure CBF due to its reproducibility and low coefficient of variation.17-19 The PC MRI maximum encoding velocity (Venc) must be chosen to prevent phase wrapping that can confound analysis while adequate resolution is necessary to estimate flow through the vessels of interest. Designing time efficient protocols is clinically important and requires an understanding of the desired imaging regions. Therefore, we measured the peak velocity and vessel size of the internal carotid (ICA) and vertebral arteries (VA) in children and adults to assist with the design of PC MRI protocols to measure cerebral blood flow.

Methods

We consented pediatric patients undergoing clinical MR exams and adult volunteers (CHLA-18-00439 & CCI 11-00083 respectively) before imaging. Images were obtained with a Philips (Best, Netherlands) Achieva 3T magnet and eight-element head coil. A magnetic resonance angiogram localized the vessels in the neck, and a PC MR imaging plane was placed approximately 1 cm above the carotid bifurcation. The angiogram was collected in the axial plane with inline reformatting into sagittal and coronal planes to facilitate orthogonal placement of the PC imaging plane. Image parameters for the PC MR examinations were as follows. For children: TR=26.5 ms TE=16.9 ms, FOV=100x100 mm2, slice=5 mm, NSA=6, acquisition matrix=224×224, reconstruction matrix=448×448; Venc=40 cm/s. For adults: TR=12.3 ms TE=7.5 ms, FOV=260x260 mm2, slice=5 mm, NSA=10, acquisition matrix=204×201, reconstruction matrix=448×448, Venc=200 cm/s.Three authors (HW, IS, JCW) processed all images by using ImageJ (to un-alias PC MR as needed) and Matlab or ImageJ to manually draw regions of interest around vessels and measured their mean and peak velocities (cm/s) and cross-sectional areas (mm^2). We computed the flow through each vessel (mean velocity × cross sectional area), total cerebral blood flow (total of the two ICA and two VA flows), and the ratio of the flow through each vessel to the total cerebral blood flow. We then evaluated for differences between these ratios in ICAs and VAs for both children and adults using a two-way ANOVA.

Results

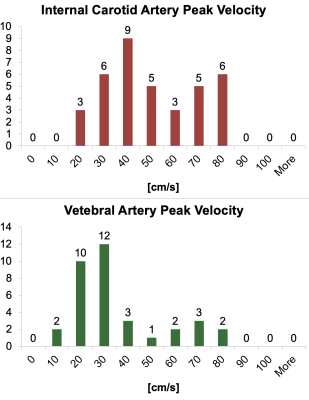

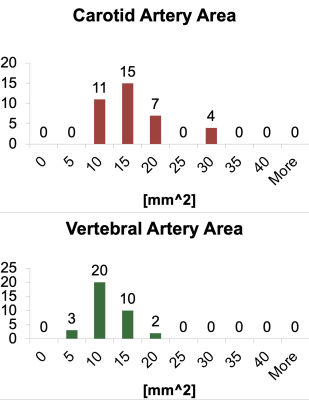

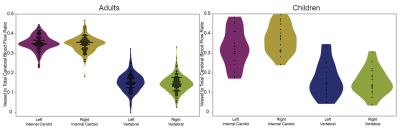

Our images included 19 children (11M/8F, mean age 2.3±1.3 years, range 0.4-5.1 years) and 66 adults (mean age 23.5±9.7 years). In children the peak velocities ranged from 20-80 cm/s in ICAs and 10-80 cm/s in the VAs (figure 2) and the cross sectional areas in their arteries ranged from 10-30 mm2 for ICAs and 5-20 mm2 for VAs (figure 3). Vessel flow to total CBF ratios in adults were left ICA=0.3520±0.0387, right ICA=0.3477±0.0388, left VA=0.1537±0.0489, and right VA=0.1466±0.0438; in children, ratios were left ICA=0.327±0.0957, right ICA=0.374±0.0734, left VA=0.167±0.091, and right VA=0.147±0.077 (figure 4). The two-way ANOVA demonstrated that the ratios of vessel flow to total CBF was the same (p=0.339) for adult and child groups. As expected, the ratio of the flow through the vessel depends (p<0.0001) on whether the vessel is an ICA or VA.Discussion

Phase contrast is a good candidate for measurement of CBF in a wide age range due to its relatively straight forward acquisition and robust flow quantitation. The highest peak velocity recorded in both ICAs and VAs was 80 cm/s, making Venc of 80cm/s a reasonable starting point for all ages to maximize dynamic range while reducing the likelihood of phase wrapping.The ICAs were larger than the VAs, with the minimum cross sectional area being 5mm^2 demonstrated in 3 VAs. Acquisitions should capture at least 3 voxels without partial voluming inside the vessel lumen for flow measurements. As such, a reasonable starting point for acquired voxel size is to take the square root of the vessel area and divide by 3. Thus, image resolution should be finer in children due to their smaller vessels. A reasonable starting point of 0.74mm^2 pixel size would successfully capture flow in the smallest vessels measured in this study.

Conclusion

Phase contrast is a robust approach for estimating CBF in a wide age range of human subjects. Additional work will be needed to assess the robustness of PC MRI to more challenging situations including subject motion and non-parallel vessels.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

- LASSEN NA. Cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption in man. Physiol Rev 1959; 39: 183-238. DOI: 10.1152/physrev.1959.39.2.183.

- Liu P, Qi Y, Lin Z, et al. Assessment of cerebral blood flow in neonates and infants: A phase-contrast MRI study. Neuroimage 2019; 185: 926-933. 2018/03/10. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.03.020.

- Paniukov D, Lebel RM, Giesbrecht G, et al. Cerebral blood flow increases across early childhood. Neuroimage 2020; 204: 116224. 2019/09/24. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116224.

- Oshima T, Karasawa F and Satoh T. Effects of propofol on cerebral blood flow and the metabolic rate of oxygen in humans. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2002; 46: 831-835. DOI: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460713.x.

- Jennings JR, Heim AF, Kuan DC, et al. Use of total cerebral blood flow as an imaging biomarker of known cardiovascular risks. Stroke 2013; 44: 2480-2485. 2013/07/23. DOI: 10.1161/strokeaha.113.001716.

- King KS, Sheng M, Liu P, et al. Detrimental effect of systemic vascular risk factors on brain hemodynamic function assessed with MRI. Neuroradiol J 2018; 31: 253-261. 2018/01/10. DOI: 10.1177/1971400917750375.

- Yu C, Lu W, Qiu J, et al. Alterations of the Whole Cerebral Blood Flow in Patients With Different Total Cerebral Small Vessel Disease Burden. Front Aging Neurosci 2020; 12: 175. 2020/06/23. DOI: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.00175.

- Leijenaar JF, van Maurik IS, Kuijer JPA, et al. Lower cerebral blood flow in subjects with Alzheimer's dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and subjective cognitive decline using two-dimensional phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2017; 9: 76-83. 2017/11/02. DOI: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.10.001.

- Hanaoka T, Kimura N, Aso Y, et al. Relationship between white matter lesions and regional cerebral blood flow changes during longitudinal follow up in Alzheimer's disease. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2016; 16: 836-842. 2015/08/05. DOI: 10.1111/ggi.12563.

- Borzage MT, Bush AM, Choi S, et al. Predictors of cerebral blood flow in patients with and without anemia. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2016; 120: 976-981. 2016/01/21. DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00994.2015.

- Prohovnik I, Hurlet-Jensen A, Adams R, et al. Hemodynamic etiology of elevated flow velocity and stroke in sickle-cell disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2009; 29: 803-810. 2009/02/11. DOI: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.6.

- Vernooij MW, van der Lugt A, Ikram MA, et al. Total cerebral blood flow and total brain perfusion in the general population: the Rotterdam Scan Study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008; 28: 412-419. 2007/07/11. DOI: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600526.

- Sabayan B, van der Grond J, Westendorp RG, et al. Total cerebral blood flow and mortality in old age: a 12-year follow-up study. Neurology 2013; 81: 1922-1929. 2013/10/30. DOI: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000436618.48402.da.

- Leaver AM, Vasavada M, Joshi SH, et al. Mechanisms of Antidepressant Response to Electroconvulsive Therapy Studied With Perfusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Biol Psychiatry 2019; 85: 466-476. 2018/10/05. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.09.021.

- Chen W, Liu P, Volkow ND, et al. Cocaine attenuates blood flow but not neuronal responses to stimulation while preserving neurovascular coupling for resting brain activity. Mol Psychiatry 2016; 21: 1408-1416. 2015/12/15. DOI: 10.1038/mp.2015.185.

- Christie IC, Price J, Edwards L, et al. Alcohol consumption and cerebral blood flow among older adults. Alcohol 2008; 42: 269-275. DOI: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.03.132.

- Koerte I, Haberl C, Schmidt M, et al. Inter- and intra-rater reliability of blood and cerebrospinal fluid flow quantification by phase-contrast MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013; 38: 655-662. 2013/01/31. DOI: 10.1002/jmri.24013.

- Sakhare AR, Barisano G and Pa J. Assessing test-retest reliability of phase contrast MRI for measuring cerebrospinal fluid and cerebral blood flow dynamics. Magn Reson Med 2019; 82: 658-670. 2019/04/25. DOI: 10.1002/mrm.27752.

- Liu P, Lu H, Filbey FM, et al. Automatic and reproducible positioning of phase-contrast MRI for the quantification of global cerebral blood flow. PLoS One 2014; 9: e95721. 2014/05/02. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095721.

Figures

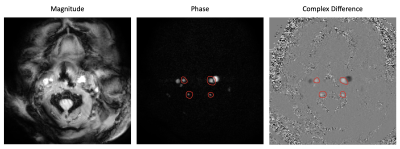

An example of magnitude, phase, and complex

difference images acquired with a typical phase contrast protocol. Vessel selection of the internal carotid

arteries (top) and vertebral arteries (bottom) is demonstrated with red

circles.

Histogram assessment of peak flow velocity in the internal

carotid (top panel) and vertebral (bottom panel) arteries.

Histogram assessment of vessel area in the internal

carotid (top panel) and vertebral (bottom panel) arteries.

Violin plots of ratio of vessel to total CBF for adults (left panel) and children (right panel).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/2310