2295

Real-time phase contrast sequences versus conventional phase contrast sequences in cerebral blood flow quantification: an in vivo study1CHIMERE UR 7516, Jules Verne University of Picardy, Amiens, France, 2Medical Image Processing Department, Amiens Picardy University Hospital, Amiens, France, 3Radiology Department, Amiens Picardy University Hospital, Amiens, France, 4Neurosurgery Department, Amiens Picardy University Hospital, Amiens, France

Synopsis

Keywords: Blood vessels, Velocity & Flow, real time phase contrast, phase contrast, cerebral blood flow

Real-time phase contrast sequences (RT-PC) appear to have great potential in clinical applications. However, it is important to validate RT-PC in the quantification of cerebral blood flow prior to its use in clinical applications. In this study, we analyzed RT-PC accuracy by comparing the segmentation area, flow rate and pulsatility index of cerebral vessels obtained from RT-PC and conventional phase contrast sequences. RT-PC with 2×2 mm2 spatial resolution and 75ms/image temporal resolution can accurately quantify cerebral blood flow rate with an error of less than 3%. Higher temporal resolution in RT-PC could improve accuracy in cerebral arterial flow quantification.

Introduction

Compared to conventional phase contrast sequences (CINE-PC)1, real-time phase contrast sequences (RT-PC) can provide a continuous beat-to-beat flow signal, with shorter acquisition times, no need of cardiac gating and insensitive to motion. These features make RT-PC of great potential for clinical applications and scientific research2.Recently, an increasing number of studies have employed RT-PC to quantify cerebral blood flow3-5. The smaller cross-sectional area of cerebral vessels and the higher pulsatility index of cerebral arteries compared to cerebrospinal fluid make RT-PC more demanding in terms of spatial and temporal resolution.

Validation of the accuracy of RT-PC in the quantification of cerebral blood flow is an important requirement prior to its clinical application. The purpose of this study is to analyze the accuracy of RT-PC by first quantifying the segmented area, flow rate and pulsatility index of cerebral arterial and venous flow and then comparing the results with those obtained by CINE-PC.

Methods

− Image acquisition26 healthy volunteers (age: 19~35; 13 women) were examined using a clinical 3T scanner with a 32 channels head coil. Only 13 volunteers’ data from a previous study were used for the comparison of cerebral arteries6. The direction of arterial flow is considered positive toward the brain and for venous flow toward the heart.

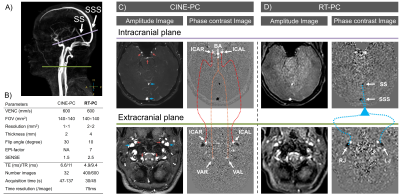

The CINE-PC of this study consists of a gradient-recalled echo phase contrast sequence with a finger plethysmograph used as cardiac gating. The RT-PC consists of a multi-shot, gradient-recalled echo-planar imaging sequence. The parameters for the two sequences are shown in Fig.1-B.

CINE-PC and RT-PC were performed on two planes to quantify the cerebral arteries and venous blood flow (Fig.1-A). The intracranial plane contains three arteries (ICAR=right internal carotid artery, ICAL= left internal carotid artery and BA=basilar artery) and two veins (SS=straight sinus and SSS=superior sagittal sinus). The extracranial plane contains four arteries (ICAR=right internal carotid artery, ICAL= left internal carotid artery, VAR=right vertebral artery and VRL=left vertebral artery) and two veins (RJ=right internal jugular and LJ=left internal jugular vein). The location and trajectory of the vessels are shown in Fig.1-C&D.

− Image Processing

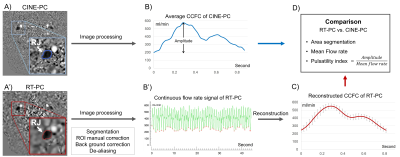

The image processing was performed using the software – Flow 2.07,8.

First, the region of interest (ROI) of each vessel was defined and manually corrected in case of movement. Next, a stationary region close to the target vessel was defined for background field correction. If aliasing is present, it can be corrected with the de-aliasing function. The flow rate signal of the target vessel was then extracted (Fig.2-A&B).

− Signal Processing & Comparison

The cardiac cycle flow curve (CCFC) of CINE-PC was used as reference. For the comparison, the software first automatically locates the minimum value of each CCFC in the continuous signal as segmentation points to extract multiple independent CCFCs. These CCFCs are then interpolated over 32 sampling points to finally reconstruct an average CCFC of RT-PC (Fig.2B’-C).

The accuracy of RT-PC was evaluated by comparing the reconstructed mean CCFC with the reference CCFC from CINE-PC (Fig.2-D).

− Statistical analysis

Paired Student’s t-test or Paired Wilcoxon’s test was used to detect the differences. Correlation between two groups was detected using the Spearman test. A Bland and Altman analysis was used to quantify the degree of agreement between RT-PC and CINE-PC. The threshold for significance was set to p < 0.05.

Results

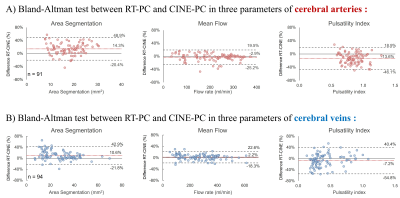

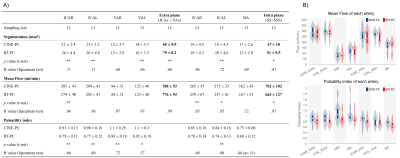

Fig.3 and Fig.4 show the quantification results of CINE-PC and RT-PC for each of the cerebral arteries and veins. The extracranial vessels presented a higher flow rate. In both planes the flow rate and pulsatility index of arteries were greater than those of veins.Fig.5 shows the Bland-Altman plot between RT-PC and CINE-PC. Compared to CINE-PC, RT-PC segmented area was overestimated (arteries: 14% and veins: 11%) and the pulsatility index was smaller, especially in arteries (arteries: -14% and veins: -7%). However, the flow rate error between the two sequences was small (arteries: -3% and veins: 2%).

Discussion

The cerebral blood flow parameters quantified in this study were similar to those of previous studies9,10.In this study, the spatial resolution in RT-PC was twice the resolution set in CINE-PC, which is the main reason for the over-segmentation presented in RT-PC. The use of lower spatial resolution can effectively increase the signal-to-noise ratio and improve temporal resolution. Indeed, according to a previous study, RT-PC can be adapted to a lower spatial resolution11. Although some over-segmentation was shown in RT-PC sequences, the error of cerebral blood flow rate quantification does not exceed 3% using a spatial resolution of 2×2 mm2.

The flow rate waveform of cerebral veins is smoother than that of arteries, which makes RT-PC more accurate for quantifying the pulsatility index in cerebral veins.

Conclusion

It is important to choose an optimal spatial and temporal resolution when quantifying cerebral blood flow by RT-PC.RT-PC with 2×2 mm2 spatial resolution and 75ms/image temporal resolution can accurately quantify cerebral blood flow. Further studies increasing the temporal resolution of the RT-PC could improve the accuracy in cerebral arterial flow quantification.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by EquipEX FIGURES (Facing Faces Institute Guiding Research), European Union Interreg REVERT Project, Hanuman ANR-18-CE45-0014 and Region Haut de France. Thanks to the staff members at the Facing Faces Institute (Amiens, France) for technical assistance. Thanks to David Chechin from Phillips industry for his scientific support.References

- Pelc NJ, Herfkens RJ, Shimakawa A, Enzmann DR. Phase contrast cine magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance quarterly. 1991 Oct 1;7(4):229-54.

- Zhang S, Joseph AA, Voit D, Schaetz S, Merboldt KD, Unterberg-Buchwald C, Hennemuth A, Lotz J, Frahm J. Real-time magnetic resonance imaging of cardiac function and flow—recent progress. Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery. 2014 Oct;4(5):313. http://dx.doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2014.06.03.

- Balédent O, Liu P, Lokossou A, Fall S, Metanbou S, Makki M. Real-time phase contrast magnetic resonance imaging for assessment of cerebral hemodynamics during breathing. In ISMRM 2019-International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2019 May 11. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03736882.

- Liu P, Fall S, Metanbou S, Balédent O. Real-Time Phase Contrast MRI to quantify Cerebral arterial flow change during variations breathing. In ISMRM 2022-International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2022 May 7. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03736876.

- Laganà MM, Pirastru A, Ferrari F, Di Tella S, Cazzoli M, Pelizzari L, Jin N, Zacà D, Alperin N, Baselli G, Baglio F. Cardiac and Respiratory Influences on Intracranial and Neck Venous Flow, Estimated Using Real-Time Phase-Contrast MRI. Biosensors. 2022 Aug 8;12(8):612. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios12080612.

- Liu P, Fall S, Balédent O. Use of real-time phase-contrast MRI to quantify the effect of spontaneous breathing on the cerebral arteries. NeuroImage. 2022 Jun 7:119361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2022.119361.

- Liu P, Lokossou A, Fall S, Makki M and Bamendent O, 2019. Post Processing Software for Echo Planar Imaging Phase Contrast Sequence. In ISMRM 27th, (4823).

- Liu P, Fall S, Balédent O. Flow 2.0-a flexible, scalable, cross-platform post-processing software for realtime phase contrast sequences. In ISMRM 2022-International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2022 May 7. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2207.12712

- Wåhlin A, Ambarki K, Hauksson J, Birgander R, Malm J, Eklund A. Phase contrast MRI quantification of pulsatile volumes of brain arteries, veins, and cerebrospinal fluids compartments: repeatability and physiological interactions. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2012 May;35(5):1055-62. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.23527.

- Lokossou A, Metanbou S, Gondry-Jouet C, Balédent O. Extracranial versus intracranial hydro-hemodynamics during aging: a PC-MRI pilot cross-sectional study. Fluids and Barriers of the CNS. 2020 Dec;17(1):1-1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12987-019-0163-4.

- Liu P, Fall S, Baledent O. Accuracy of Real-Time Echo-Planar Imaging Phase Contrast MRI. In ISMRM 2021-International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2021 May 16. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03738468.

Figures

Figure 1: Image acquisition of CINE-PC and RT-PC in two planes. The locations of the intracranial (purple) and extracranial (green) planes are shown in angiography images (A). Amplitude and phase contrast images acquired by CINE-PC (C) and RT-PC (D) using the protocol in B. The seven cerebral arteries and the four cerebral veins with their trajectories are shown in C and D, respectively.

Figure 2: Image processing in RT-PC vs. CINE-PC flow. A) An example of RJ segmentation with CINE-PC (blue) and RT-PC (Red). B) Flow rate signal obtained by CINE-PC (top, an averaged CCFC with 32 sampling points) and RT-PC (bottom, continuous flow rate signal with 600 sampling points); the red dots in RT-PC signal indicate the minimum values of each CCFC. C) Reconstructed CCFC (red) from all CCFCs. D) Parameters analyzed in the two CCFCs.

Figure 3: Results and distribution of segmented area, mean flow rate, and pulsatility index of each cerebral artery in CINE-PC and RT-PC. Paired Student’s t-test or Paired Wilcoxon’s test was performed, * indicates p < 0.05, and ** indicates p < 0.01. Correlation analysis performed with the Spearman test, the correlation coefficient R is shown in the table. ICAR=right internal carotid artery, BA=basilar artery, VRL=left vertebral artery.

Figure 4: Results and distribution of segmented area, mean flow rate, and pulsatility index of each cerebral vein in CINE-PC and RT-PC. Paired Student’s t-test or Paired Wilcoxon’s test was performed, * indicates p < 0.05, and ** indicates p < 0.01. Correlation analysis performed with the Spearman test, the correlation coefficient R is shown in the table. SS = straight sinus, SSS = superior sagittal sinus, RJ = right internal jugular vein, Extra = extracranial plane; Intra = intracranial plane.