2261

Imaging perfusion in the vertebral bone marrow and subchondral bone using FAIR ASL1Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: MSK, Perfusion, lumbar spine, low back pain

Some patients with chronic low back pain (cLBP) do not show any diagnosable conditions in conventional imaging methods. Studies suggested that pain could be associated with the degeneration of vertebral endplate region in those nonspecific cLBP patients. The endplates around degenerating discs experience trauma, which leads to inflammation, angiogenesis, neurogenesis and infection. Currently, there is no established method to diagnose such pathologies. We previously reported associations between increased endplate perfusion and experience of cLBP using DCEMRI. In this study we explored Arterial Spin Labeling to avoid using contrast agents. Results show that FAIR could be used to study endplate perfusion.Introduction

The majority of Chronic low back pain (cLBP) is associated with degeneration of the intervertebral disc. Disc degeneration can lead to various clinically recognizable conditions1–6, which can be diagnosed and treated using established methods. However, if a patient does not display these clear clinical signs and symptoms, it is considered as a case of nonspecific cLBP7–10. Studies suggested that nonspecific cLBP could be associated with Modic changes, which describes the degeneration of vertebral bone marrow11–14. Modic changes are thought to be a sequela of initial trauma in the subchondral bone and ensuing inflammation and infection propagating to the bone marrow15. In fact, a histology study demonstrated that in some patients with non-specific cLBP, the subchondral bones underwent structural damage and ensuing angiogenesis and nerve growth, sensitizing the area to stimulation and pain4. Note that not all Modic changes might have the same etiology and those with inflammation and infection might be more likely to be associated with pain15. Currently, there is no established diagnostic method for assessment of such vertebral endplate pathologies.Previously, our team used Dynamic Contrast Enhanced MRI (DCEMRI) to study perfusion changes in endplates and demonstrated that those DCEMRI measures correlated with pain assessments16. However, concerns about the use of Gadolinium based contrast agents required alternatives. This study explored the feasibility of Flow-Sensitive Alternating Inversion Recovery (FAIR) ASL for imaging perfusion in the vertebrae.

Methods

MRI scans were acquired from five subjects with no known spinal disorders (ages 23y-36y, mean=28.2), using a 3T GE MRI system (Waukesha, WI USA). The study was approved by the IRB and participants gave written consents. FAIR scans were acquired with single-shot fast spin echo with several combinations of acquisition parameters: TR=6s, FOCI inversion pulse with four TIs: [1.25, 1.5, 1.8, 2.2] seconds, and global presaturation on or off. 15 non-selective and slab-selective inversion pairs were acquired for each TI. Selective inversion was in the axial plane with 40mm thickness to label spins in the descending aorta. A single 10mm thick axial slice was imaged on the caudal endplate of L1 vertebra. This slice also included kidneys, allowing us to use perfusion in kidneys as a benchmark. Total acquisition time was 186s. Acquisitions were repeated with phase encode direction right/left or anterior/posterior to observe the impact of motion artifacts. In the last two subjects respiratory gating was also tested to further reduce motion artifacts.Perfusion estimates were calculated using BASIL17. Acquisitions with four TIs were concatenated and PASL model was selected with T1Vertebra=0.93s, T1blood=1.65s. A set of single proton density images acquired at the end of each FAIR series were averaged for each subject and used for calibrated perfusion calculations.

Results

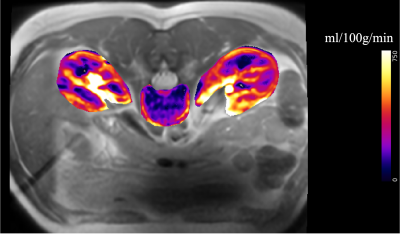

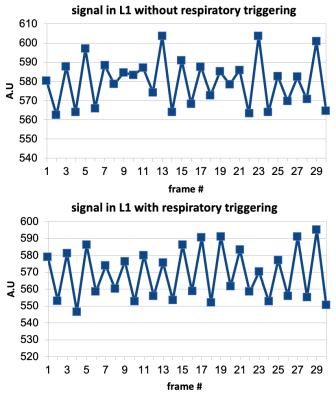

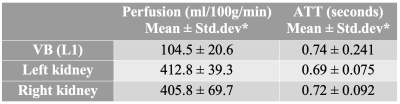

Fig.1 shows the axial slice from one of the participants with perfusion map overlaid in color. Perfusion and arterial transit time (ATT) estimates are listed in Table-1. Kidney perfusion estimates were in accord with the literature18,19. Perfusion in L1 was about four times lower compared to the kidneys. Inter-subject variations were around 20% for the vertebral perfusion and 10%-17% in the kidneys. ATT measurements in kidneys were also similar to the published values.There was noticeable improvement in the stability of ASL signal in the vertebra when respiratory triggering was used (Fig.2). Temporal SNR was 1.7 without triggering and 3.4 with triggering. Although motion artifacts were greatly reduced with left/right phase encoding direction compared to anterior/posterior, the kidneys moving on the two sides of the lumbar column still induced some phase errors. TR increased to about 7s when respiratory triggering was on. Global saturation did not affect the outcome noticeably.

Discussion

This study explored the feasibility of FAIR ASL to image perfusion in the bone marrow and subchondral bone of the vertebrae. Successful implementation of this technique might help detect endplate degeneration and its potential contribution to cLBP.The perfusion measurements in L1 were consistent across subjects in this small cohort of healthy subjects. The calibrated ASL measurements from kidneys were consistent with those published earlier, suggesting that the perfusion in L1 endplate is about 100ml/100g/min. Note that our earlier work with DCEMRI showed that the signal increased 2-4 fold in degenerating endplates20, which is possibly mediated by angiogenesis and endplate microfractures in degenerating endplates as reported earlier4. Therefore, FAIR could be able to detect such large changes in perfusion and offer sufficient sensitivity and specificity to detect endplate abnormalities.

Note that 10mm axial slice contains both the subchondral bone and bone marrow perfusion. This could be helpful in understanding the underlying pathophysiological basis of Modic endplate changes, particularly those cases that might lead to cLBP. On the other hand, one could aim for thinner slices (~1-2mm) to image perfusion only in the subchondral bone, which might help monitor earlier stages when endplates undergo the degenerative changes described above.

Conclusion

Use of FAIR ASL to investigate perfusion in vertebral bodies is feasible, which could help identify degeneration in subchondral bone and vertebral bone marrow. Such abnormalities have been shown to correlate with non-specific low back pain15,21.Acknowledgements

This study is supported in part by funds from Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin endowment. We would like to thank study participants for their help and participation on this study.References

1. Andersson, G. B. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet 354, 581-585 (1999).

2. de, S., E. I. et al. The association between lumbar disc degeneration and low back pain: the influence of age, gender, and individual radiographic features. Spine 35, 531-536 (2010).

3. Luoma, K. et al. Low back pain in relation to lumbar disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25, 487-492 (2000).

4. Ohtori, S. et al. Tumor necrosis factor-immunoreactive cells and PGP 9.5-immunoreactive nerve fibers in vertebral endplates of patients with discogenic low back Pain and Modic Type 1 or Type 2 changes on MRI. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 31, 1026-1031 (2006).

5. Fields, A. J., Liebenberg, E. C. & Lotz, J. C. Innervation of pathologies in the lumbar vertebral end plate and intervertebral disc. Spine J 14, 513-521 (2014).

6. Lotz, J. C., Fields, A. J. & Liebenberg, E. C. The role of the vertebral end plate in low back pain. Global Spine J3, 153-164 (2013).

7. Brinjikji, W. et al. MRI Findings of Disc Degeneration are More Prevalent in Adults with Low Back Pain than in Asymptomatic Controls: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 36, 2394-2399 (2015).

8. Brinjikji, W. et al. Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 36, 811-816 (2015).

9. Määttä, J. H., Wadge, S., MacGregor, A., Karppinen, J. & Williams, F. M. ISSLS Prize Winner: Vertebral Endplate (Modic) Change is an Independent Risk Factor for Episodes of Severe and Disabling Low Back Pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 40, 1187-1193 (2015).

10. van den Berg, R. et al. The Association Between Self-reported Low Back Pain and Radiographic Lumbar Disc Degeneration of the Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee (CHECK) Study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 42, 1464-1471 (2017).

11. Albert, H. B. et al. Modic changes, possible causes and relation to low back pain. Med Hypotheses 70, 361-368 (2008).

12. Kjaer, P., Korsholm, L., Bendix, T., Sorensen, J. S. & Leboeuf-Yde, C. Modic changes and their associations with clinical findings. Eur Spine J 15, 1312-1319 (2006).

13. Modic, M. T., Steinberg, P. M., Ross, J. S., Masaryk, T. J. & Carter, J. R. Degenerative disk disease: assessment of changes in vertebral body marrow with MR imaging. Radiology 166, 193-199 (1988).

14. Rahme, R. & Moussa, R. The modic vertebral endplate and marrow changes: pathologic significance and relation to low back pain and segmental instability of the lumbar spine. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 29, 838-842 (2008).

15. Rajasekaran, S. et al. Are Modic changes ‘Primary infective endplatitis’?-insights from multimodal imaging of non-specific low back pain patients and development of a radiological ‘Endplate infection probability score’. Eur Spine J 31, 2884-2896 (2022).

16. Arpinar, V. E., Gliedt, J. A., King, J. A., Maiman, D. J. & Muftuler, L. T. Oswestry Disability Index scores correlate with MRI measurements in degenerating intervertebral discs and endplates. Eur J Pain 24, 346-353 (2020).

17. Chappell, M. A., Groves, A. R., Whitcher, B. & Woolrich, M. W. Variational Bayesian inference for a nonlinear forward model. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 57, 223-236 (2008).

18. Kim, D. W. et al. Measurement of arterial transit time and renal blood flow using pseudocontinuous ASL MRI with multiple post-labeling delays: Feasibility, reproducibility, and variation. J Magn Reson Imaging 46, 813-819 (2017).

19. Robson, P. M. et al. Strategies for reducing respiratory motion artifacts in renal perfusion imaging with arterial spin labeling. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 61, 1374-1387 (2009).

20. Arpinar, V. E., Rand, S. D., Klein, A. P., Maiman, D. J. & Muftuler, L. T. Changes in perfusion and diffusion in the endplate regions of degenerating intervertebral discs: a DCE-MRI study. Eur Spine J 24, 2458-2467 (2015).

21. Li, R. et al. Vertebral endplate defects are associated with bone mineral density in lumbar degenerative disc disease. Eur Spine J 31, 2935-2942 (2022).

Figures