2251

Deep learning reconstruction for liver T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted imaging:Improvement of image quality and lesion delineation1Department of Radiology, Ruijin Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China, 2MR Research, GE Healthcare, Beijing, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Liver, Tumor, Magnetic resonance imaging, T2-weighted imaging, DIffusion weighted imaging

In this study, deep learning reconstruction (DLR) of liver fast spin echo T2-weighted (FSE-T2WI) and diffusion-weighted (DWI) was performed. The results showed the liver SNR, and lesion CNR were dramatically increased for both the FSE-T2WI and DWI with DLR compared with conventional reconstruction. The image quality of DLR FSE-T2WI even surpassed that of the routinely used PROPELLER T2WI. DLR didn’t impact the quantitative apparent coefficient derived from DWI. T2WI and DWI with DLR also improved the delineation of lesion structure due to improvement of image quality. Our study indicated DLR FSE-T2WI and DWI would be beneficial for liver disease diagnosing.Introduction

Liver diseases, such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and hepatic metastatic tumors, have an impact on a large population1. T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) play important roles in liver MRI for detecting liver diseases like HCC2. However, conventional fast-spin-echo based T2WI (FSE-T2WI) and DWI usually suffer from low signal-to-noise-ratio (SNR) within clinical accepted scan time.A vendor provided deep learning reconstruction (DLR) has been introduced recently to improve MRI image quality by denoising and alleviating truncation artifacts. This novel DLR has been applied in pituitary and prostate MRI, showing significantly improved image quality and diagnostic performance in lesion detection3, 4. With these promising findings, we assumed that DLR might also hold clinical potential in liver MRI by providing image improved FSE-T2WI and DWI, which can further help for hepatic lesion delineation. We thus aimed to investigate these in this study.

Material and Methods

Patients42 patients with focal liver lesions were selected in this study.

MRI experiments

All MRI acquisitions were performed at 3T scanner (Signa Architect; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) using a 30-channel flexible coil. A breath-hold fat-suppressed FSE-T2WI was obtained with the following parameters: TR/TE, 4000ms/87ms; FOV, 400mm×400 mm; matrix size, 132×132; slice thickness, 6 mm; slice number, 28; two breath-holds; scanning time, 36 seconds. For comparison, a respiratory-gated fat-suppressed PROPELLER T2WI (PRO-T2WI), routinely applied in clinic, was also acquired using following parameters: TR/TE, 3000-6000ms/85ms; FOV, 400mm×400 mm; matrix size, 132×132 slice thickness, 6 mm; slice number, 28; scanning time,, 2min30s-4min. A respiratory-gated DWI was also performed with TR/TE= 500ms/63ms, FOV=400mm×400 mm, matrix size=132×132, slice thickness=6mm, slice number=28, three b values (0, 50 and 800 s/mm2), and scan time of 2min30s-4min31s. DLR with noise reduction was set as high level (75%) to reconstruct the FSE-T2WI and DWI.

Data analysis

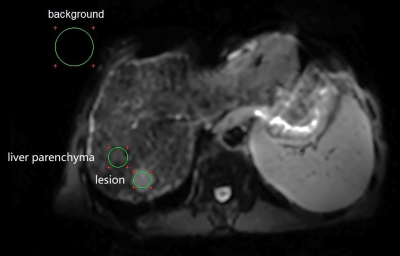

Overall image quality was independently reviewed by two radiologists with more than 3 years of experience in abdominal imaging using a 5-point scale4. Quantitative liver SNR and lesion contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) were calculated using the vender provided workstation (ADW 4.4; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, CA, USA). The liver SNR was defined as the mean signal of liver dividing by the standard derivation (SD) of background noise. The lesion CNR was calculated with dividing the signal difference between lesion and liver by the background SD. Figure 1 showed an example definition of the ROIs . DWI derived apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map was generated with a mono-exponential model by the vendor provided workstation.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software. The variables, unless otherwise stated, were reported as median (lower quartile, upper quartile) and were compared using Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test with Bonferroni correction for non-normal distribution. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

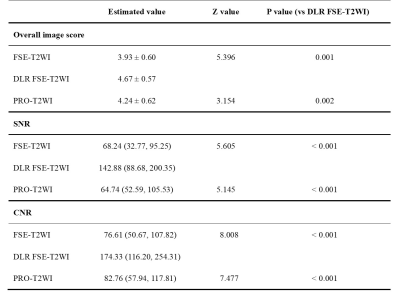

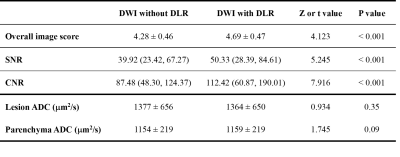

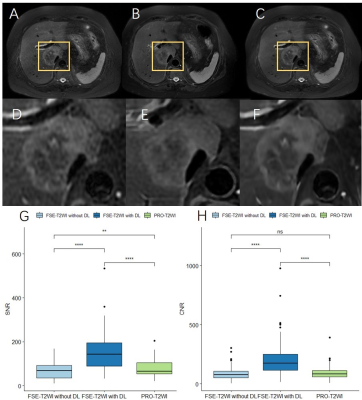

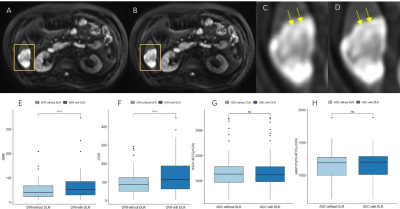

85 focal liver lesions were detected in the finally selected 42 patients. Compared with FSE-T2WI and routinely used PRO-T2WI, DLR FSE-T2WI provided improved image quality as indicated by significantly higher overall image scores, liver SNRs, and lesion CNRs (all P<0.05; Table 1). Similar results were also observed for DWI with and without DLR (Table 2). Despite a significant improvement of liver SNR and lesion CNR, DLR didn’t impact the DWI derived ADC for both liver parenchyma and lesions significantly (all P>0.05; Table 2).As shown in Fig.2, lesion showed lower SNR in conventional FSE-T2WI than in PRO-T2WI, while comparable CNRs were found between both images. Using DLR, FSE-T2WI presented significantly increased SNR and CNR of lesion than PRO-T2WI. Moreover, DLR FSE-T2WI depicted the clearest boundaries of the necrosis within tumor than other images (Fig. 2 D-F). As shown in Fig. 3, DWI (b=800 s/mm2) with DLR also improved the delineation of necrosis within tumor due to significantly increased SNR and CNR. Some details can be clearly inspected in DLR DWI but hardly distinguished in conventional DWI (denoted by yellow arrows in Fig. 3 C and D).

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, we investigated the clinical value of DLR in liver T2WI and DWI. The results demonstrated that DLR can significantly improve the SNR and CNR of imaging, which further provided better delineation of lesion structure. Despite the improvement of image quality, DLR didn’t significantly affect the quantitative ADC derived from DWI.PRO-T2WI was routinely used in clinic because it provides motion-insenitive image quality compared with FSE-T2WI5. Our study also supported this. However, with the help of DLR, the image quality of FSE-T2WI dramatically increased and surpassed that of PRO-T2WI. The DLR FSE-T2WI also presented better delineation of lesion structure (Fig. 2). In addition, the scanning time was significantly reduced in FSE-T2WI than PRO-T2WI.

Ueda et al., had reported DLR improved the image quality of prostate DWI without an impact on ADC3. Similar results were observed for liver DWI with DLR in this study. Our results also showed DWI with DLR better delineated lesion and could differentiate some necrosis regions which were hardly visible in DWI without DLR (Fig. 3).

In conclusion, DLR can significantly improve the image quality and the delineation of lesion structure for liver T2WI and DWI.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1.Llovet J, Kelley R, Villanueva A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2021; 7(1): 6.

2.Chernyak V, Fowler K, Kamaya A, et al. Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System (LI-RADS) Version 2018: Imaging of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in At-Risk Patients. Radiology, 2018; 289(3): 816-30.

3.Ueda T, Ohno Y, Yamamoto K, et al. Deep Learning Reconstruction of Diffusion-weighted MRI Improves Image Quality for Prostatic Imaging. Radiology, 2022; 303(2): 373-81.

4.Kim M, Kim H, Kim H, et al. Thin-Slice Pituitary MRI with Deep Learning-based Reconstruction: Diagnostic Performance in a Postoperative Setting. Radiology, 2021; 298(1): 114-22.

5.Kang K, Kim Y, Kim E, et al. T2-Weighted Liver MRI Using the MultiVane Technique at 3T: Comparison with Conventional T2-Weighted MRI. Korean J Radiol, 2015; 16(5): 1038-46.

Figures