2234

Imaging findings and differential diagnosis of hyperintense hepatocellular carcinoma on hepatobiliary phase of Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI1Nantong Haimen People’s Hospital, Nantong, China, 2the Third Affiliated Nantong Hospital of Nantong University, Nantong, China, 3Philips Healthcare, Beijing, China, 4Philips Healthcare, Shanghai, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Liver, Cancer, HCC

This study evaluates imaging features that can help to differentiate hyperintense HCC from non-HCC benign and malignant lesions. On HBP images, hyperintense nodules can be differentiated with several imaging characteristics, especially HBP hypointense rim, and a focal defect in contrast uptake, that indicate the diagnosis of hyperintense HCCs.Introduction

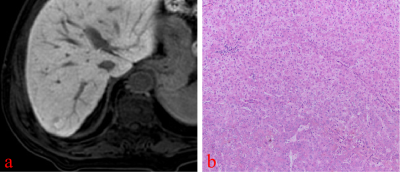

Gadoxetic acid disodium (Gd-EOB-DTPA) is a liver-specifific contrast material having the properties of both extracellular and hepatobiliary contrast materials, thereby enabling both dynamic and hepatobiliary phase imaging1. On hepatobiliary phase (HBP) images of EOB-MRI, HCCs are usually hypointense because of the lack of uptake of the contrast material by the tumor, whereas the background liver shows peak enhancement at this phase2. However, 10%~15% HCCs appear hyperintense on HBP images due to increased uptake of the contrast material, we refer to such lesions as hyperintense HCCs3. However, some benign lesions such as focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) and malignant lesions such as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) also show appear hyperintense on HBP images4. Due to the lack of experience, the misdiagnosis rate is relatively high. Imaging features that can help to differentiate hyperintense HCC from benign or malignant lesions have not been well established. The purpose of our study was to define imaging features that may help characterize hyperintense lesions seen on HBP images of Gd-EOB-DTPA.Methods

In a review of our radiology information database from May 2017 to April 2020, we retrieved the records of 89 patients who had a hyperintense nodule on hepatobiliary phase images. A hyperintense nodule was defined as one in which at least two thirds of the lesion area was hyperintense relative to adjacent liver on hepatobiliary phase images.The final study sample was 89 lesions in 89 patients (58 men, 31 women; mean age, 63.4 years; range, 45–81 years). The 89 lesions were 23 HCCs, 18 non-HCC malignant lesions (intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, ICC, n=9; combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma, cHCC-ICC, n=3; hepatic metastases, HM, n=6), and 48 non-HCC benign lesions (FNH and FNH-like lesions, n=25; dysplastic nodules, DN, n=19; hepatic adenoma,HCA, n=1; cavernous hemangioma of liver, CHL, n=3). Two observers independently reviewed imaging features and calculated lesion-liver signal intensity ratios (LLR) on HBP images. The ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis H test, chi-square test, and Fisher's exact probability method were used to analyze the parameter differences between HCC, non-HCC malignant lesions, and benign lesions. Multivariate Logistic regression analysis was employed to identify the independent risk factors of hyperintense HCC and non-HCC hyperintense benign and malignant lesions. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to assess the efficacy of hyperintense HCC.Results

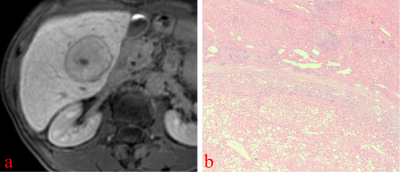

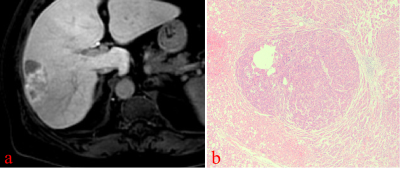

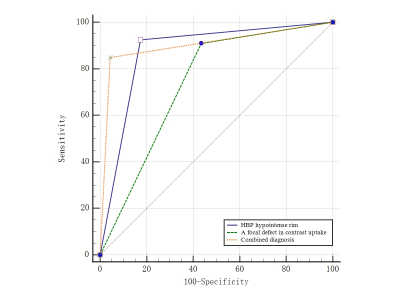

On HBP images, hyperintense HCC more commonly had HBP hypointense rim (82.6% vs 0%, p<0.001; 82.6% vs 10.4%, p< 0.001), focal defects in uptake (56.5% vs 16.7%, p=0.012; 56.5% vs 6.3%, p< 0.001), and “nodule-in-nodule” architecture (47.8% vs 0%, p<0.001; 47.8% vs 0%, p<0.001). Non-HCC malignant lesions more commonly had “EOB cloud” sign (77.8% vs 0%, p<0.001; 77.8% vs 0%, p<0.001). Non-HCC benign lesions more commonly had “EOB scar” sign (37.5% vs 4.3%, p=0.003; 37.5% vs 0%, p<0.001) The mean LLR of HCC, non-HCC benign and malignant lesions were not significantly different (x2=1.93, p=0.152). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that HBP hypointense rim (OR=81.16, 95%CI 11.51~572.33, p<0.001), and a focal defect in contrast uptake (OR=11.04, 95%CI 1.62~75.39, p=0.014), were independent predictors for hyperintense HCCs. The area under curve (AUC) of HBP hypointense rim, a focal defect in contrast uptake, and combined diagnosis in the diagnosis of hypointense HCCs were 0.875, 0.737, and 0.903, respectively.Conclusion

On HBP images, hyperintense nodules can be differentiated with several imaging characteristics, especially HBP hypointense rim, and a focal defect in contrast uptake, that indicate the diagnosis of hyperintense HCCs.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found

References

1. Kim YY, Park MS, Aljoqiman KS, et al. Gadoxetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: Hepatocellular carcinoma and mimickers[J]. Clin Mol Hepatol, 2019, 25(3):223-233.

2. Fujita N, Nishie A, Asayama Y, et al. Hyperintense Liver Masses at Hepatobiliary Phase Gadoxetic Acid-enhanced MRI: Imaging Appearances and Clinical Importance[J]. Radiographics, 2020, 40(1):72-94.

3. Kitao A, Matsui O, Yoneda N, et al. Differentiation Between Hepatocellular Carcinoma Showing Hyperintensity on the Hepatobiliary Phase of Gadoxetic Acid-Enhanced MRI and Focal Nodular Hyperplasia by CT and MRI[J]. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2018, 211(2):347-357.

4. Suh YJ, Kim MJ, Choi JY, et al. Differentiation of hepatic hyperintense lesions seen on gadoxetic acid-enhanced hepatobiliary phase MRI[J]. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2011, 197(1):W44-W52.

5. Kim JW, Lee CH, Kim SB, et al. Washout appearance in Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MR imaging: A differentiating feature between hepatocellular carcinoma with paradoxical uptake on the hepatobiliary phase and focal nodular hyperplasia-like nodules[J]. J Magn Reson Imaging, 2017, 45(6):1599-1608.

6. An C, Rhee H, Han K, et al. Added value of smooth hypointense rim in the hepatobiliary phase of gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI in identifying tumour capsule and diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Eur Radiol, 2017, 27(6):2610-2618.

Figures