2225

High-level and modular description of MRI sequences using domain-specific language1Fraunhofer Institute for Digital Medicine MEVIS, Bremen, Germany, 2German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence DFKI, Bremen, Germany, 3University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany, 4Faculty 1 (Physics/Electrical Engineering), University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany, 5mediri GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Pulse Sequence Design, Software Tools

This work demonstrates the formulation of MRI sequences in a high-level Domain Specific Language (DSL). The DSL approach reduces the complexity of MR sequence programming and enables optimization of preconfigured DSL parameters using MR simulations. Finally, using the gammaSTAR framework, DSL sequences can be directly run on real MR scanners.Introduction

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is one of the most versatile imaging techniques and thus indispensable in modern medical diagnostics. However, it can be a complicated task for the clinician to find optimal sequence parameters to answer a specific clinical question due to the sheer complexity of modern MRI sequences. Therefore, automated optimization strategies of these parameters could be a useful support for the clinician. Such optimization however is difficult since most MR sequences are implemented rather rigidly in vendor-depended frameworks using low-level languages such as C++. To date, different optimization approaches were proposed1,2,3. However, the high number of degrees of freedom and the restricted area of use is a problem, which has not been sufficiently addressed so far. Domain Specific Languages (DSL)4 could overcome this hurdle by allowing the formulation of MRI sequences on various abstraction levels in a generalized fashion. To this aim, we demonstrate the formulation of a high-level DSL which allows easy construction of various types of MRI sequences. Using this DSL, generation of valid MRI sequences using the gammaSTAR framework5 is demonstrated and simulation of MR images using the Jemris simulator6 is demonstrated.Methods

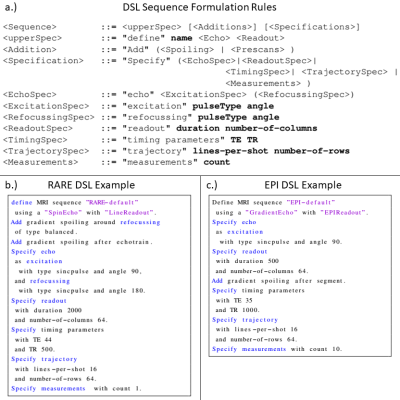

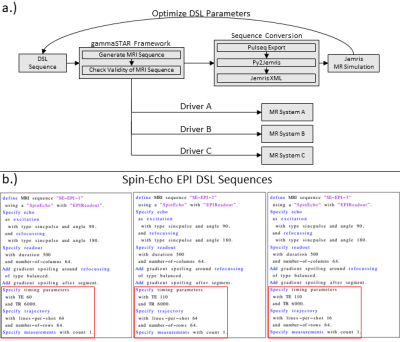

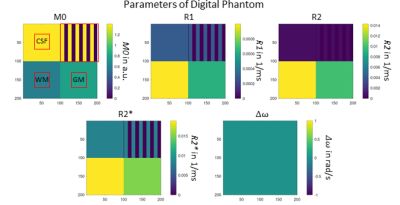

A high-level DSL should enable the formulation of MRI sequences in the most simplified way. Therefore, the basic definition and separation of MRI sequences is accomplished by the echo and readout specification. The rules of the proposed DSL are shown in Fig. 1a. The first line defines the name, the echo as well as the readout type of the MRI sequence. This alone would allow the generation of valid MR sequences by setting all additional specifications to default values. However, the DSL also allows to explicitly formulate specifications and additions. In terms of specifications, it is possible to define the pulse type and flip angle of excitation and refocusing pulses. In addition, the readout can have a specified readout duration and a distinct number of columns. Third, timing parameters like TE and TR can be specified. Finally, the trajectory can be refined with the specification of the acquired lines per shot and the number of rows. It is also possible to define the number of measurements/repetitions. Additions define sequence elements which can be added to the basic sequence configuration. Examples are prescans or additional spoiler gradients. Fig. 1b demonstrates the formulation of a RARE and a Spin-Echo EPI sequence using the given formulation rules. Fig. 2 shows how a sequence, which is formulated in the proposed DSL, is transferred to MR systems and the Jemris MR simulator. The gammaSTAR framework is used to generate RF, gradient and ADC events from the DSL sequence configuration. This also incorporates a validity check to ensure physical plausibility. Using Pulseq exports7 and the Py2Jemris tool8, a Jemris XML file can be generated, which allows simulation of the sequence with custom digital phantoms. The simulated MRI signals can the be used for calculation of various image metrics which allows optimization of the DSL parameters. Using different gammaSTAR drivers, the sequence can also directly be applied to MR systems of different vendors. This work demonstrates the configuration and simulation of different DSL sequences. Therefore, different variants of a Spin-Echo EPI sequence are generated in the proposed DSL as shown in Fig. 2b. Using Jemris together with a custom phantom (cf. Fig. 3), raw MR signals are simulated, and images are reconstructed using a python script. T1, T2 and T2* relaxation times of different squares of the phantom are chosen to correspond to typical values of tissue as encountered in brain imaging (CSF, gray matter, white matter)9.Results

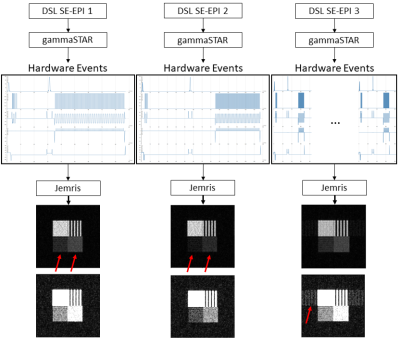

Generated hardware events from the different DSL configurations are shown in Fig. 4. Simulated images show lower signals with longer TE values show when comparing SE-EPI 1 and SE-EPI 2. SE-EPI 3 shows residual ghosting signal when compared to the other two configurations.Discussion

Results demonstrate successful application of DSL sequences to MR simulations. The visual appearance of images reflects the different configurations of the DSL sequences. Ghosting arises due to differences in magnetization states when image segmentation is applied. Lower signal with longer TE arises due to increased T2 decay. These variations would allow optimization of MR sequences before they are played out at the actual MR system by calculating quantitative image metrics. In future work, additional layers of the DSL will be proposed, which allow more flexibility for more advanced users. A second DSL layer would then e.g., allow to further specify the different pulse shapes of excitation and refocusing pulses in terms of parameters such as the time-bandwidth product etc. The lowest DSL level could finally give access to the actual RF, gradient and ADC events of the MR system, achieving a maximum of flexibility.Conclusion

This work demonstrates the application of domain-specific languages to the complex problem of MR sequence programming. A high-level DSL is proposed which allows straight-forward implementation of various types of MR sequences, drastically reducing the mentioned complexity. Using the gammaSTAR framework, these DSL sequences can be simulated for optimization purposes or directly transferred to the MR system for real MRI measurements.Acknowledgements

We received grant money from the AI Center for Health Care of the U Bremen Research Alliance, financially supported by the Federal State of Bremen in Germany.

Jörn Huber, Daniel Christopher Hoinkiss and Christina Plump contributed equally to this work.

References

1. A Loktyushin, K Herz, N Dang et al., MRzero - Automated discovery of MRI sequences using supervised learning, Magn Reson Med. 2021 Aug; 86(2):709-724

2. Stephen P. Jordan, Siyuan Hu, Ignacio Rozada, Debra F. McGivney, Automated design of pulse sequences for magnetic resonance fingerprinting using physics-inspired optimization, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118(40)

3. R B Lufkin, R Keen, M Rhodes, J Quinn, W Glenn, W Hanafee, MRI simulator for instruction in pulse-sequence selection, AJR Am J Roentgenol, 1986 Jul;147(1):199-202

4. Mernik, M., Heering, J., and Sloane, A. M. (2005). When and how to develop domain-specific languages, ACM Computing Surveys 37, 316–344, Mezura-Montes, E. and Coello, C. (2006).

5. Cordes, C., Konstandin, S., Porter, D., and Günther, M. (2020). Portable and platform-independent mr pulse sequence programs. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 83, 1277–1290

6. Stöcker, T., Vahedipour, K., Pflugfelder, D., and Shah, N. J. (2010). High-performance computing MRI simulations. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 64, 186–193.

7. Layton, K. J., Kroboth, S., Jia, F., Littin, S., Yu, H., Leupold, J., et al. (2016). Pulseq: A rapid and hardware-independent pulse sequence prototyping framework. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 77

8. Tong, G., Geethanath, S., and Vaughan, J. T. (2021). Bridging open source sequence simulation and acquisition with py2jemris. Proceedings of the 29th Annual Conference of ISMRM

9. Bojorquez, J. Z., Bricq, S., Acquitter, C., Brunotte, F., Walker, P. M., and Lalande, A. (2017). What are normal relaxation times of tissues at 3 t? Magnetic Resonance Imaging 35, 69–80

Figures