2222

Merging Cartesian and non-Cartesian sampling through GoLF-SPARKLING1Neurospin, CEA Paris Saclay, Gif-sur-Yvette, 91191, France, 2Inria, MIND, Palaiseau, 91120, France, 3Siemens Healthineers, Saint-Denis, 93210, France

Synopsis

Keywords: New Trajectories & Spatial Encoding Methods, Brain

Cartesian sampling can acquire a given k-space region with minimum redundancy, while non-Cartesian sampling can help achieve a larger k-space coverage. Through generalized affine constraints in SPARKLING and an adapted target sampling density, for the first time non-Cartesian and Cartesian sampling are merged within same trajectory, giving the best of both worlds. With Gridding of Low Frequencies (GoLF), we get SPARKLING k-space trajectories which carry out Cartesian sampling at the center of k-space. This approach paves the way for designing new kind of compound sampling patterns, which enforces Cartesian and non-Cartesian sampling within the same trajectory.

Introduction

Recently, SPARKLING1 was introduced (and extended to 3D2) as a means to optimize k-space sampling pattern according to a prescribed target sampling density while each underlying non-Cartesian k-space trajectory followed the MR hardware constraints, particularly maximum gradient and slew rate.A limitation of these SPARKLING trajectories is the oversampling at k-space center which results from affine echo time (TE) constraints, where we limit the shots to pass through the center of k-space at TE to obtain images for a given target contrast. This results in strong oversampling with respect to Nyquist criteria which can be detrimental to image quality as it induces increased off-resonance artifacts due to multiple trajectories crossing the center of k-space along different trajectory paths. Further, such oversampling is sub-optimal as these extra samples can be used to sample higher frequencies resulting in improved image reconstructions with finer details in structures.

Theory and notation

From2, a k-space sampling pattern \(\mathbf{K}=(\mathbf{k}_i)_{i=1}^{N_c}\) is composed of \(N_c\) shots, with each 3D shot composed of \(N_s\) samples acquired over the readout duration such that \(\mathbf{k}_i(t)=(k_{i,x}(t),k_{i,y}(t),k_{i,z}(t))\). For simplicity, the 3D k-space sampling domain is normalized to \(\Omega=[-1,1]^3\). The trajectory \(\mathbf{K}\) is optimized1,2 within the constraint set \(\mathbf{K}\in\mathcal{Q}_{{\mathbf{A}},{\mathbf{b}}}^{N_c}\) which ensures each k-space sampling trajectory satisfies the MR hardware constraints and the affine constraint: \[\begin{aligned} {\mathbf{A_i}}{\mathbf{k_i}}={\mathbf{b_i}}\quad\forall\textrm{}i\in{1\dots\textrm{}N_c}\end{aligned}\] The above constraint is specified to obtain the required target contrast, which is achieved by crafting \({\mathbf{A}}\) and \({\mathbf{b}}\), such that \({\mathbf{k}}_i[k_{\textrm{TE}}]=[0,0,0]^T\) is enforced3, where \(k_{\textrm{TE}}\) is the k-space sample index corresponding to sampling at TE.Methods

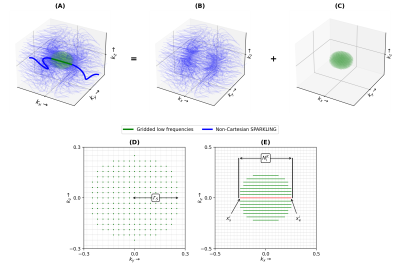

In order to mitigate such oversampling issues, note that an optimal way to sample a region of k-space at Nyquist with minimum redundancy is through Cartesian sampling. We use this fact and generalize the affine constraints into our constraint set \(\mathcal{Q}_{{\mathbf{A}},{{\mathbf{b}}}}^{N_c}\) such that we impose Cartesian sampling at center of k-space. Each k-space sample shot \({\mathbf{k}}_i,\forall\textrm{}i\textrm{}\in\{1,\dots,N_c\}\), is constrained to pass through the lower frequencies in the form of a Cartesian line as shown in Fig.1. This constraint is enforced by crafting individual \({\mathbf{A}}_i\) and \({\mathbf{b}}_i\) in a specific manner for each shot \(i\).In practice, we cover a sphere \(\mathcal{S}\) in the center of k-space with Cartesian sampling as shown in Fig.1(A). The entire k-space trajectory can be split into a non-Cartesian (Fig.1(B)) and Cartesian (Fig.1(C)) complementary parts. Further, for mathematical simplicity, we assume the image matrix dimensions to be equal, i.e. \(\tilde{N}=N_x=N_y=N_z\), while extensions to non-isotropic matrix sizes can be carried out as the k-space sampling domain is normalized in \(\Omega\in[-1,1]^3\). Particularly, we cover \(\mathcal{S}\) with straight line readouts along \(x\) as shown in Fig.1(E), and cover a circle of radius \(r_\mathcal{S}\) in \(k_y\) and \(k_z\) encoding directions as seen in Fig.1(D).

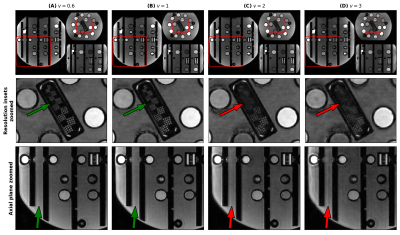

During the Cartesian line readout (Fig.1(E)), as the scanner can play k-space trajectory at different speeds, we introduce \(v\ge0\) as the number of Nyquist voxel steps \(\Delta x\) taken in readout direction per gradient raster time \(\Delta t\) by the trajectory at center of k-space. The purpose of \(v\) is to control the trajectory velocity at k-space center to manage the tradeoff between time spent to sample low and high frequency k-space data.

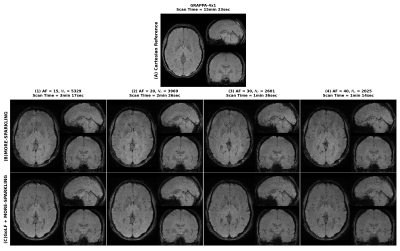

Acquisitions were carried out at 3T using a 64-channel head/neck coil array. With NIST phantom4 (Fig.2), \(v\) was varied to tune it as NIST embodies resolution insets, which can be used to quantify image quality. The in vivo scan (Fig.3) was done at varying acceleration factors (AF=\(\frac{\tilde{N}^2}{N_c}\)) from 15 to 40 for both MORE-SPARKLING5 as baseline and GoLF+MORE-SPARKLING trajectories to assess how image quality evolves as a function of scan time.

Results

Fig.2 shows an increase in artifact level appearing first at \(v=2\) and becoming more prominent for \(v=3\) (red arrow bottom-row). In zoomed visualization for \(v>1\), we see significant losses in the details, indicating that \(v\leq1\) is better for \(\textrm{T}_2^*\)-w imaging at 3T. Within this range, we choose \(v=1\) to have the highest possible velocity and spend minimum time in the center of k-space and collect more samples in the high-frequency region, resulting in sharper edges.From Fig.3, we observe that GoLF feature provides less noisy and more detailed images as compared to the sole MORE-SPARKLING trajectories. The image quality is preserved up to AF=20 for GoLF+MORE-SPARKLING trajectories while we observe degradation at AF=20 for MORE-SPARKLING. Additionally, a direct diagonal comparison can be drawn between the two approaches: Image quality at AF=20, 30 and 40 for GoLF+MORE-SPARKLING trajectories is similar to MORE-SPARKLING trajectories at AF=15, 20 and 30, respectively.

Conclusion

A novel compound sampling approach is introduced to measure the k-space with trajectories having both Cartesian and non-Cartesian parts to extract the best of both worlds. With GoLF, improved reconstructed image quality was obtained with reduced noise level and clearer visibility in the structures, speeding up scans by 6.3x compared to GRAPPA-4.Additionally, sensitivity maps can be computed in all scans through IFFT of the central Cartesian k-space data. As an extension to this, parallel imaging methods like GRAPPA6, SENSE7 and CAIPIRINIA8 can now be incorporated in non-Cartesian sampling to further increase the AF or improve the image clarity at a given AF.

Acknowledgements

The concepts and information presented in this abstract are based on research results that are not commercially available. Future availability cannot be guaranteed. This work was granted access to the HPC resources of IDRIS under the allocation 2021-AD011011153 made by GENCI. Chaithya G R was supported by the CEA NUMERICS program, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 800945.

References

1. Lazarus, C., & others. (2019). SPARKLING: variable-density k-space filling curves for accelerated T2*-weighted MRI. Magn. Reson. Med., 81(6), 3643–3661.

2. Chaithya, G. R., & others. (2022). Optimizing Full 3D SPARKLING Trajectories for High-Resolution Magnetic Resonance Imaging. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 41(8), 2105–2117. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2022.3157269

3. Chauffert, N., & others. (2016). A projection algorithm for gradient waveforms design in MRI. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag., 35(9), 2026–2039.

4. NIST/NIBIB Medical Imaging Phantom Lending Library. (2021). In NIST. https://www.nist.gov/programs-projects/nistnibib-medical-imaging-phantom-lending-library

5. Chaithya, G. R., Daval-Frérot, G., & others. (2022, May). MORE-SPARKLING: Non-Cartesian trajectories with Minimized Off-Resonance Effects. 30th Proceedings of Ismrm.

6. Griswold, M. A., & others. (2002). Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA). Magn. Reson. Med., 47(6), 1202–1210.

7. Pruessmann, K. P., Weiger, M., Scheidegger, M. B., & Boesiger, P. (1999). SENSE: Sensitivity encoding for fast mri. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 42(5), 952–962. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1522-2594(199911)42:5<952::AID-MRM16>3.0.CO;2-S

8. Breuer, F. A., & others. (2005). Controlled aliasing in parallel imaging results in higher acceleration (caipirinha) for multi-slice imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 53(3), 684–691. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.20401

Figures

Fig.1: GoLF-SPARKLING trajectory for \(N_c=256\), with \(\tilde{N}=64\) (lower matrix size \(\tilde{N}=64\) and number of shots \(N_c\) is chosen for clearer visualization) which is composed of (B) non-Cartesian SPARKLING portion in blue and (C) Gridded low frequencies in green. Slice profile of the Cartesian portion of the k-space trajectory is presented along (D) \(k_x\) = 0 plane and (E) \(k_y\) = 0 plane.

Fig.2: Prospective results for GoLF-SPARKLING with varying trajectory velocity at the center of k-space on NIST phantom with k-space velocity as (A) \(v = 0.6\), (B) \(v = 1\), (C) \(v = 2\) and (D) \(v = 3\). We show slices from each orientation (top row), the zoomed in region into the resolution insets (mid-row) and zoomed in region in axial plane (bottom row).