2221

Imaging Biomarkers of Therapeutic Response to Melanoma to Kinase Inhibitors1Departments of Radiology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States, 2Department of Radiation Oncology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Acquisition, Cancer

In vivo 1H/31P MRS were used to monitor the effects of Kinase Inhibitor (KI) therapy in two metabolically different human melanoma xenografts models. Our goal is to determine the metabolic changes in human melanoma xenograft models when treated with two KIs, a BRAF and a MEK inhibitor. KI combination is more effective than single-drug therapy. Differences in relative levels of metabolites and bioenergetics between two human melanoma xenografts models may produce differential therapeutic responses to BRAF and MEK inhibitors. In melanoma, metabolic changes in response to targeted kinase inhibitor therapy occur rapidly and are connected to subsequent tumor response.INTRODUCTION:

Melanoma is a malignancy of melanocytes and is highly curable when limited to the primary site.(1) However, metastatic melanoma confers a poor prognosis with a median survival of 6 months.(2) Targeted therapy approach for metastatic melanoma has been focused on the mitogen-activated protein kinases (i.e., the MAPK pathway). MAPK kinases regulate diverse cellular programs relying upon extracellular signals to produce intracellular responses like proliferation, gene expression, differentiation, mitosis, cell survival, and apoptosis. This report focuses on the response of the human DB-1 and WM983B models of melanoma to two kinase inhibitors (KIs) – dabrafenib and trametinib, which target the BRAF and MEK kinases, respectively. These kinases are components of the MAPK signaling pathway.(3) Both melanoma models express a gene mutation replacing glutamine with valine at DNA sequence position 600, which is expressed by 40-60% of human melanoma patients, ninety percent of whom simultaneously express both BRAF and MEK mutations. Furthermore, studies suggest that simultaneous blockade of BRAF and MEK kinases generates more significant and more lasting responses than the blockade of either of these enzymes alone.(4) Our goal is to develop 1H/31P MRS methods for detecting tumor response to chemotherapy in two metabolically different human melanoma xenografts model.METHODS:

31P/1H MRS experiments were performed in 60 tumor-bearing mice. Thirty DB-1 and 30 WM983B xenografts were studied. Each xenograft cohort was divided into the following groups: control (n=6), dabrafenib alone (n=8), trametinib alone (n=8), and dabrafenib + trametinib (n=8).DB-1 and WM983B human melanoma cells were grown as described elsewhere.(5) Each mouse was inoculated subcutaneously with 10 x 106 cells/ml in a 0.1mL suspension. 31P/1H MRS experiments were performed on a 9.4 T Bruker magnet using a homemade 1H/31P dual-tuned coil. For the MRS experiments, tumor-bearing mice were anesthetized with % isoflurane in 1 L/min oxygen. A respiration pillow and a rectal thermistor were used to monitor the mouse's respiration and core temperature at 37 ± 1°C. 3-APP (Amino Propenyl Phosphonate) was injected into the mouse peritoneum before putting the animal in a magnet. 3-APP allows the measurement of extracellular pH (pHe).(6) For 1H MRS, a slice-selective, double-frequency, Hadamard-selective, multiple quantum coherence (Had-Sel-MQC) transfer pulse sequence was used to detect lactate and alanine, filtering out overlapping lipid signals.(7) On the other hand, intracellular pH (pHi), pHe, and bioenergetics indices (βNTP/Pi) were measured using 31P MRS. 1H/31P MRS exams were acquired on Day 0 (pre-), Day 2, and Day 5 (post-) of treatment. Dabrafenib (30 mg/kg; oral), trametinib (10 mg/kg; oral), and dabrafenib + trametinib (similar dose) were given using methods described elsewhere.(6) Tumor volumes were measured using calipers. Independent paired t-tests were performed for statistical analysis using SPSS 20. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.RESULTS:

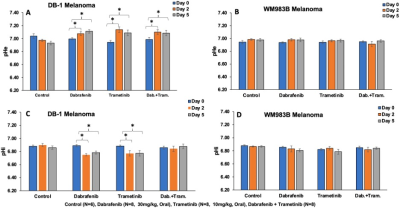

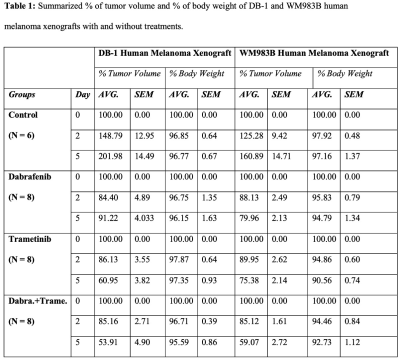

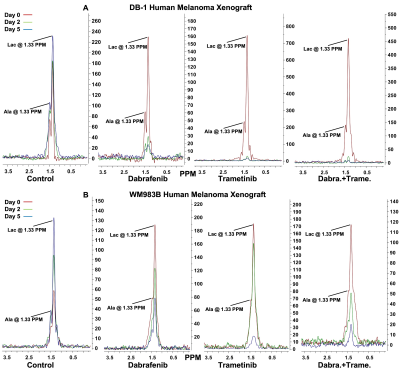

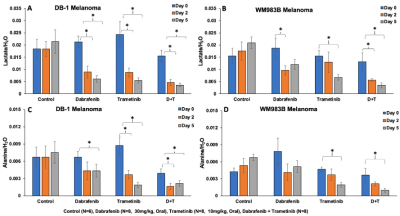

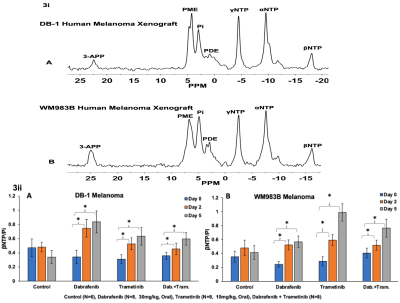

The metabolic effects of dabrafenib and trametinib were monitored by 1H/ 31P MRS as a function of time on days 0, 2, and 5 of treatment. The Had-Sel-MQC sequence was used because it yields high-field methyl resonances from lactate and alanine. Given this, total levels of lactate and alanine were detected by measuring the areas of their high-field methyl resonances (Fig. 1, 2). The 31P spectrum of the tumor models consists of well-resolved low-field resonances of β-NTP and Pi. Therefore, the bioenergetics (β-NTP/Pi) of both melanoma models could be quantitated (Fig. 3i). We did not observe any significant changes in the β-NTP/Pi value in the control groups of both xenografts after treatment with dabrafenib, trametinib, or their combination. However, following treatment with dabrafenib, trametinib, and its combination produced similar and statistically significant changes in bioenergetic status in both models DB-1 and WM983B human melanoma xenografts from day 0 to day 2, and from day 0 to day 5 (Fig. 3ii). Alkaline shifts in pHe, though small, were detected following treatment of DB-1 melanoma with dabrafenib or trametinib or with both drugs simultaneously (Fig. 4). Intracellular pH exhibited a slight acidic shift following treatment with dabrafenib or trametinib but not following simultaneous treatment with both agents. Regarding therapy response, we observed a decrease in tumor volume after treatment with dabrafenib, trametinib, and dabrafenib plus trametinib in both melanoma models, however as expected, control mice untreated with either drug exhibited a monotonic increase in tumor volume (Table 1).DISCUSSION:

We have previously shown and confirmed that DB-1 relies more on glycolysis than WM-983B.(5) The same phenomenon appears to be confirmed with dabrafenib and trametinib. We also noted that higher total energy levels (i.e., higher ATP) correlated with increased response to dabrafenib and trametinib. Thus, the more glycolytic and/or more energetic tumor [DB-1] appears more responsive to these drugs. The reason for the correlation of response with cellular energy state or extent of glycolysis remains to be determined. Bioenergetics and glycolytic measurements might form the basis of predictive estimates of the response of melanoma patients to an energetically demanding treatment. It is realistic to think that evidence about metabolism could also be highly valuable in monitoring and predicting responses to other cancers and treatment modalities, such as BRAF and MEK inhibitors and immunotherapy. Future studies are needed to illuminate the nature of the link between the observed changes and correlate with biochemical assays.Acknowledgements

NIH R01CA250102-01; NIH R01CA228457-01A1; NIH R01CA268601-01References

1. Leiter U, Garbe C. Epidemiology of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer--the role of sunlight. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;624:89-103.

2. Davis LE, Shalin SC, Tackett AJ. Current state of melanoma diagnosis and treatment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2019;20(11):1366-79.

3.Vashi sht Gopal YN, Gammon S, Prasad R, Knighton B, Pisaneschi F, Roszik J, et al. A Novel Mitochondrial Inhibitor Blocks MAPK Pathway and Overcomes MAPK Inhibitor Resistance in Melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(21):6429-42.

4. Eroglu Z, Ribas A. Combination therapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors for melanoma: latest evidence and place in therapy. Therapeutic advances in medical oncology. 2016;8(1):48-56.

5. Nath K, Roman J, Nelson DS, Guo L, Lee SC, Orlovskiy S, et al. Effect of Differences in Metabolic Activity of Melanoma Models on Response to Lonidamine plus Doxorubicin. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14654.

6. Nath K, Nelson DS, Ho AM, Lee SC, Darpolor MM, Pickup S, et al. 31P and 1H MRS of DB-1 melanoma xenografts: lonidamine selectively decreases tumor intracellular pH and energy status and sensitizes tumors to melphalan. NMR Biomed. 2013;26(1):98-105.

7. Pickup S, Lee SC, Mancuso A, Glickson JD. Lactate imaging with Hadamard-encoded slice-selective multiple quantum coherence chemical-shift imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2008;60(2):299-305.

Figures

Figure 3. Figure 3i: Representative in vivo localized (Image Selected In vivo Spectroscopy; ISIS) 31P MR spectra of DB-1 (A) and WM983B (B) human melanoma xenografts. Figure 3ii: The changes of βNTP/Pi [ratio of peak area: DB-1 (A), and WM983B (B)] in the different groups. *represent statistical significance.