2220

Ex vivo lymph node staging by a portable low-field MRI scanner1Magnetic Detection and Imaging, University of Twente, Enschede, Netherlands, 2Surgery, Medisch Spectrum Twente, Enschede, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Acquisition, Cancer, Lymph node, low-field, portable scanner

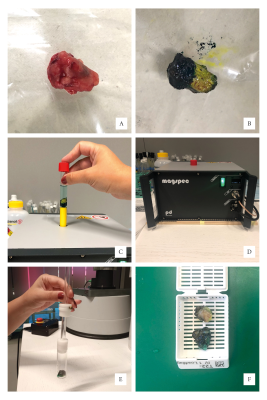

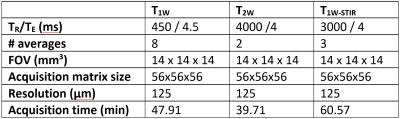

Sentinel lymph node (LN) biopsy facilitated by magnetic nanoparticles (MNP) is introduced for breast cancer patients eligible for breast conserving surgery. As m1etastatic depositions potentially introduce changes in heterogeneity of MNP-enhanced MRI, a portable low-field MRI scanner can be used for ex vivo perioperative LN staging. Therefore, we assessed the changes in T1w, T2w and STIR images due to iron deposition in LN. 2Clinically relevant LN segments, such as fat and iron depositions, identified in the pathology images, were also observable in MR scans.Methods: Patients with histologically confirmed invasive breast cancer visible on ultrasound imaging were recruited for the magnetic SLNB procedure (NTR4903) 8. Within a week prior to surgery patients received an ultrasound guided injection of 1mL magnetic tracer (Magtrace® Endomagnetics, Cambridge, UK) containing 28mg iron-oxide. Harvested LN were inked to mark their orientation prior to fixation by formaldehyde (Figure 1). The iron content of the resected LN was assessed by SPaQ5 and a lookup table6. The LN were subsequently imaged using a portable low-field MRI system (Pure Devices GmbH, Rimpar, Germany) with an increased bore of 15mm diameter at a field strength of 0.5T. The 3D spin-echo images were acquired with a field-of-view 14×14×14 mm³ and an isotropic resolution of 125μm (see Table 1): Spin echo T1-weighted (T1W), T2-weighted (T2W), and short tau inversion recovery (STIR). The inked and pathologically processed LN were subsequently lamellated at a 250µm distance. For each paraffin embedded lamella, four consecutive 2mm slices were sectioned and subsequently stained with a HE, CK8-18, CD68 PGM-1, and Perls Prussian blue. Each harvested LN was assessed on presence of iron and metastases.

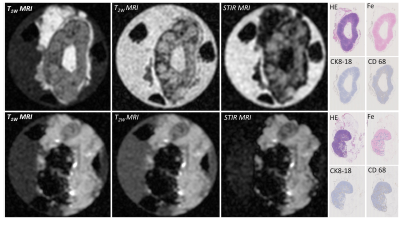

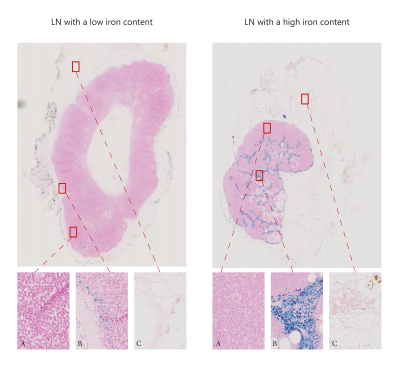

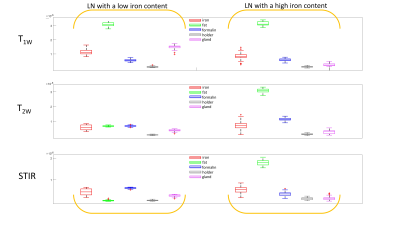

Results: This, currently ongoing, clinical trial has included three patients with five sentinel LN identified during the surgery (all negative for metastases). Iron content within these LN ranged from 2.5 to 122.3 μg. Clinically relevant LN segments, identified in the pathology images (Figure 3), illustrate clear presence of fat and iron depositions in the LN. Figure 2 illustrates the MRI and corresponding pathology images for a low and a high iron-content LN. We use pathology images (Figure 3) to validate the relevant parts of LN and therefore compare the images between LN with low and high iron content. As confirmed by pathology (Figure 3), the LN with a low iron-content show a clear fat suppression using STIR (Figure 2 – first row), while the LN with a high iron-content show less fat suppression using STIR sequence (Figure 2 – second row). As expected, comparable signal intensities for plastic holder and formalin are observed in all three MRI images regardless amount of iron trapped (Figure 4). Similarly, iron rich regions in both low and high iron content LN, have comparable signal intensity suggesting more complex MRI sequences should be utilised to assess MRI changes due to different amounts of iron trapped. Higher iron content seems to decrease T1W intensity in healthy gland tissue. Furthermore, the signal intensity of fatty tissue surrounding the LN has an increase intensity for LN with higher amount of iron trapped.

Discussion: Since 80% of SLNB procedures are clinically unnecessary, this procedure adds unresponsible morbidity for these patients. Therefore, responsibly preventing unnecessary LN resection by means of preoperative LN staging will gain ample personal healthcare benefits. The MRI images show a distinction between fat, nodal tissue and SPIO tracer (either in signal intensity or in texture) proving the feasibility of LN imaging by a portable MRI scanner at 0.5T. Given the long acquisition time, the scan protocol needs significant time reduction before implementation in clinical setting. In line with preoperative LN staging, previous research illustrate the importance of perioperative LN assessment7 for patients with limited axillary disease who remain node positive after neoadjuvant chemotherapy7.

Conclusion: The portable low-field MRI scanner can be used for ex vivo LN assessment. For clinical implementation reduction of acquisition time is necessary. A portable MRI scanner can be used for on-site high resolution imaging of excised lymph nodes with accelerated acquisition times. Clinical relevance needs to be proven by comparison of resected nodes with pathology results.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Giammarile F, Vidal-Sicart S, Paez D, et al. Sentinel Lymph Node Methods in Breast Cancer. Semin Nucl Med. Sep 2022;52(5):551-560. doi:10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2022.01.006

2. Pouw JJ, Grootendorst MR, Bezooijen R, et al. Pre-operative sentinel lymph node localization in breast cancer with superparamagnetic iron oxide MRI: the SentiMAG Multicentre Trial imaging subprotocol. Br J Radiol. 2015;88(1056):20150634. doi:10.1259/bjr.20150634

3. Johnson L, Pinder SE, Douek M. Deposition of superparamagnetic iron-oxide nanoparticles in axillary sentinel lymph nodes following subcutaneous injection. Histopathology. Feb 2013;62(3):481-6. doi:10.1111/his.12019

4. A Christenhusz FS, N de Vries, M Hofman, AE Dassen, B ten Haken, L Alic. . Potential of MR lymphography for LN staging in breast cancer. presented at: European Congress of Radiology; 2021;

5. van de Loosdrecht MM, Draack S, Waanders S, et al. A novel characterization technique for superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: The superparamagnetic quantifier, compared with magnetic particle spectroscopy. Rev Sci Instrum. Feb 2019;90(2):024101. doi:10.1063/1.5039150

6. Molenaar L, Loosdrecht MMHvd, Alic L, et al. Quantification of Magnetic Nanoparticles in ex vivo Colorectal Lymph Nodes. Nano LIFE. 2022;12(03):2250006. doi:10.1142/s1793984422500064

7. van der Noordaa MEM, Vrancken Peeters M, Rutgers EJT. The intraoperative assessment of sentinel nodes - Standards and controversies. Breast. Aug 2017;34 Suppl 1:S64-s69. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2017.06.031

8. Organization WH. International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. Accessed 09-11-2022, 2022. https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=NTR4903

Figures