2217

Vendor neutral pulse programming: Running gammaSTAR sequences on Philips Hardware1Department of Imaging Physics, Delft University of Technology, Delft, Netherlands, 2C.J. Gorter MRI Center, Radiology Department, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands, 3Imaging Physics, Fraunhofer Institute for Digital Medicine MEVIS, Bremen, Germany, 4RWTH Aachen, Aachen, Germany, 5mediri GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany, 6University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Pulse Sequence Design, Pulse Sequence Design, Vendor independent pulse programming

Pulse sequence design and development in MR is currently hindered by the possibilities to freely share pulse sequences and test these on scanners of different vendors. Vendor independent pulse programming environments provide a shareable, open, and reproducible way of pulse sequence development. An important step in this is the support on scanners of all main vendors of these protocols. In this work we show for the first time the execution of gammaSTAR imaging protocols on a Philips scanner. The obtained FLASH and RARE based images are very similar to the images obtained using the vendor’s implementation.Introduction

Development of new pulse sequence designs is one of the most important and interesting research possibilities as MR physicist. However, recreating previously designed sequences is a less interesting, less efficient, and less fruitful task. But imagine being at ISMRM and seeing an interesting new sequence that catches your attention. Many hours of pulse programming would be saved if the sequence could easily be transferred to your MRI scanner, i.e. using a QR code, without tedious re-implementation, and also independent of the used MRI vendor or software version. Moreover, this would solve the biggest limitation for open science in MRI-development for which making available the output images is much less informative than providing the sequence that was used for acquisition. Such open communication is hampered by the use of proprietary pulse programming environments of the vendors as well as non-disclosure agreements that are frequently needed to be allowed to use those environments.Vendor independent pulse programming environments 1–5 provide a shareable, reproducible and transparent way of pulse sequence development, making it possible to share developed sequences and run these at scanners of different manufacturers, enabling multi-vendor comparison. In previous work these protocols have been used at Siemens and GE, but not at Philips. In this work we show for the first time, the execution of gammaSTAR imaging protocols at a Philips scanner.

Methods

Implementation

Sequences were exported from the gammaSTAR framework in a dedicated JSON file format, listing gradient shapes, rf shapes, ADC events, container objects and timings of these container objects. This JSON file is read by the scanner using functionality written in the programming language Lua to map the events to the internal pulse sequence structure while conventional safety checks are performed. Image reconstruction is performed on the manufacturer’s hardware using the manufacturer’s reconstruction framework. Optionally, raw data can be exported and reconstructed with other open software platforms, like Gadgetron6, BART7 or Sigpy8.Experiments

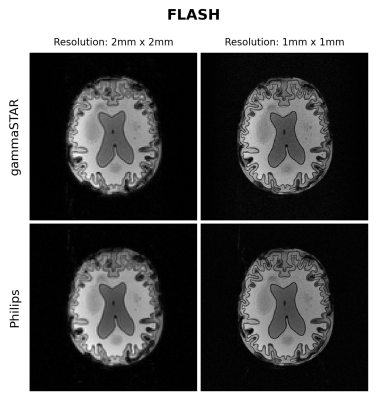

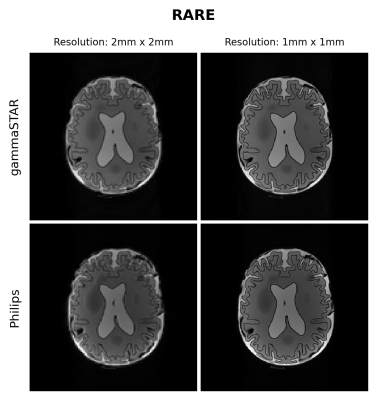

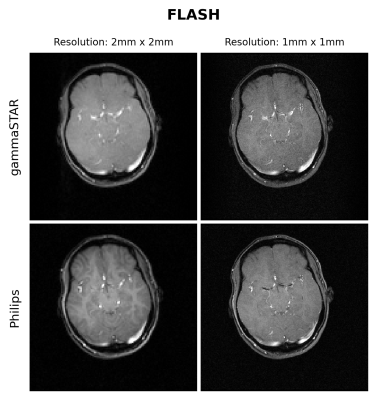

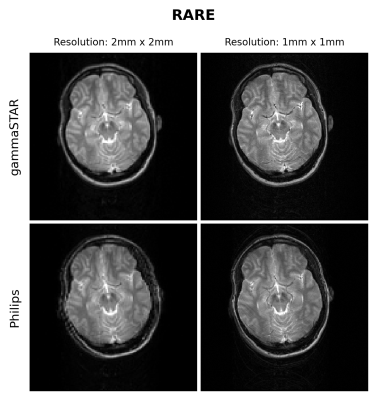

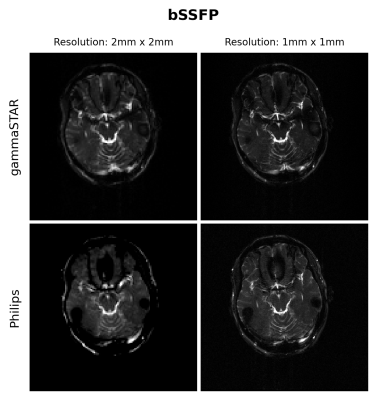

Phantom and in vivo (brain) scans were performed on a 3T Philips Achieva TX scanner (Philips, Best, The Netherlands). To perform phantom experiments a 3D-printed brain-like phantom was used, which was filled with different agar and CuSO4 concentration representing different compartments. RARE9(TE=88ms, TR=4s, FA=90°, train length = 16, https://gamma-star.mevis.fraunhofer.de/RARE_sequence_readonly.html#/ ), FLASH10 (TE=5ms, TR=12ms, FA=15°, https://gamma-star.mevis.fraunhofer.de/2D_FLASH_sequence_readonly.html#/ ) and bSSFP11 (TE=7ms, TR=14ms, FA=90°, https://gamma-star.mevis.fraunhofer.de/2D_bSSFP_sequence_readonly.html#/ ) sequences were acquired using in-plane resolutions of 1mm$$$\times$$$ 1mm and 2mm$$$\times$$$2mm with a FOV of 256mm$$$\times$$$256mm with slice thickness of 5mm. For the gammaSTAR sequences a sinc pulse shape was used together with a readout durations of 1ms (RARE) and 2ms (FLASH, bSSFP). Using the Philips interface a T1FFE (FLASH), balanced FFE (bSSFP) and T2TSE (RARE) sequence was configured with same settings (for as far as possible) as mentioned above.Results

Figures 1 and 2 show the obtained FLASH and RARE images respectively for the brain-like phantom.Figures 3,4 and 5 show the obtained FLASH, RARE and bSSFP images respectively for the in vivo scan.

Discussion and conclusion

We were able to run gammaSTAR MR sequences on the Philips MR scanner, while performing necessary hardware and subject safety checks according to the vendor’s specifications and allowing reconstruction of images directly on the scanner. Visually, the images look very similar with only slight differences between the two sequence versions in this preliminary test dataset.In the current implementation a pre-described JSON was used to provide sequence information, i.e. resembling the situation where one wants to rerun a sequence as supplied by an external party. In future work we aim to facilitate a more direct connection between scanner and the gammaSTAR framework, thereby enabling on-the-fly changes to parameters such as the geometry and to enable run-time updates, e.g. facilitating feed-back loops12. The JSON was read through Lua, a prerequisite for a direct gammaSTAR connection. Currently we used simple Cartesian acquisitions, where more complex gradient shapes and reconstructions would be an interesting next option. We also look forward to running quantitative, relaxometry MRI protocols and to compare the effect this has on reproducibility across vendors when exactly the same sequences are used, or vendor implementations as already performed using GE and Siemens MRIs 13.

In our view an open pulse programming environment can enable easier and faster transfer of knowledge between research groups (timing of gradients, rf pulses and readouts) as well as better education by allowing pulse-programming in a software environment optimized for teaching purposes. This is often an oversight in vendor supplied environments that are aimed at achieving the highest quality and flexibility. In this sense, it is also recognized that a general platform like gammaSTAR might be more restrictive than vendor-specific environments, and therefore optimal quality will be sacrificed to some extent while providing easier exchange between research groups and comparability/reproducibility between vendors. Enabling to run such sequences on a major vendor is a crucial step to broad use of these frameworks.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly funded by the Medical Delta project Dementia and Stroke 3.0.

Parts of this work were funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) under the funding code 03VP10430. The responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the authors.

References

[1] T. H. Jochimsen and M. von Mengershausen, “ODIN-object-oriented development interface for NMR,” J. Magn. Reson. San Diego Calif 1997, vol. 170, no. 1, pp. 67–78, Sep. 2004, doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.05.021.

[2] J. F. Magland, C. Li, M. C. Langham, and F. W. Wehrli, “Pulse sequence programming in a dynamic visual environment: SequenceTree,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 75, no. 1, pp. 257–265, 2016, doi: 10.1002/mrm.25640.

[3] K. J. Layton et al., “Pulseq: A rapid and hardware-independent pulse sequence prototyping framework,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 77, no. 4, pp. 1544–1552, 2017, doi: 10.1002/mrm.26235.

[4] J.-F. Nielsen and D. C. Noll, “TOPPE: A framework for rapid prototyping of MR pulse sequences,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 79, no. 6, pp. 3128–3134, 2018, doi: 10.1002/mrm.26990.

[5] C. Cordes, S. Konstandin, D. Porter, and M. Günther, “Portable and platform-independent MR pulse sequence programs,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 83, no. 4, pp. 1277–1290, 2020, doi: 10.1002/mrm.28020.

[6] M. S. Hansen and T. S. Sørensen, “Gadgetron: An open source framework for medical image reconstruction: Gadgetron,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 69, no. 6, pp. 1768–1776, Jun. 2013, doi: 10.1002/mrm.24389.

[7] M. Blumenthal et al., “mrirecon/bart: version 0.8.00.” Zenodo, Sep. 24, 2022. doi: 10.5281/ZENODO.592960.

[8] F. Ong and M. Lustig, “SigPy: a python package for high performance iterative reconstruction,” Proc. Int. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. Montr. QC, vol. 4819, 2019.

[9] J. Hennig, A. Nauerth, and H. Friedburg, “RARE imaging: A fast imaging method for clinical MR,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 823–833, 1986, doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910030602.

[10] A. Haase, J. Frahm, D. Matthaei, W. Hanicke, and K.-D. Merboldt, “FLASH imaging. Rapid NMR imaging using low flip-angle pulses,” J. Magn. Reson. 1969, vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 258–266, Apr. 1986, doi: 10.1016/0022-2364(86)90433-6.

[11] H. Y. Carr, “Steady-State Free Precession in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance,” Phys. Rev., vol. 112, no. 5, pp. 1693–1701, Dec. 1958, doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.112.1693.

[12] D. Hoinkiss, C. Cordes, S. Konstandin, and M. Günther, “Event-Based Traversing of Hierarchical Sequences Allows Real-Time Execution and Arbitrary Looping in a Scanner-Independent MRI Framework.,” in Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med 2020, Aug. 2020, p. 1043.

[13] A. Karakuzu, L. Biswas, J. Cohen-Adad, and N. Stikov, “Vendor-neutral sequences (VENUS) and fully transparent workflows improve inter-vendor reproducibility of quantitative MRI,” Bioengineering, preprint, Dec. 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.12.27.474259.

Figures