2195

Comparison of k-space Sampling Patterns for MR Fingerprinting1Biomedical Engineering Department, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Centre for the Developing Brain, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 3London Collaborative Ultra high field System (LoCUS), London, United Kingdom, 4MR Research Collaborations, Siemens Healthcare Limited, Frimley, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: MR Fingerprinting/Synthetic MR, In Silico

The temporal low-rank property of signals produced by MR Fingerprinting can be used to circumvent reconstruction of individual time frames. Instead, temporally compressed components are estimated. Since every acquired sample then contributes to every compressed component, it is unclear which k-space sampling pattern is optimal. This work collects evidence for higher robustness of radial sampling towards measurement errors and its superior ability to resolve rapidly varying temporal signals, compared to a Cartesian pattern, simulated in a realistic scenario and supported by an in vivo observation. The aim is making informed decisions about optimal sampling patterns for MRF.Introduction

In MR Fingerprinting (MRF) [1], tissue parameters are encoded by creating temporally evolving signals which are then matched to a dictionary of possible signal evolutions. In the original implementation, separate highly undersampled images of each ‘magnetisation state’ were acquired using single-shot spirals. More recently it was used that valid signals exist in a linear subspace spanned by few basis vectors, discovered by applying SVD to the dictionary [2].In this framework, every sample acquired in the k-t-domain contributes to each compressed component. This raises questions over which sampling patterns have desirable properties for MRF regarding resolution, robustness and ability to resolve temporal signals.

Intuitively, most energy and contrast information is concentrated in k-space centre, consequently it should be advantageous to sample it more frequently – hence non-Cartesian schemes such as radial sampling are popular for MRF [1-6]. Yet, non-Cartesian schemes require more samples to reach equivalent effective resolution, and it isn't clear mathematically which scheme is optimal.

This work investigates how sampling influences reconstruction quality of MRF: robustness to undersampling, errors, and ability to characterise signals which have limited temporal support.

Methods

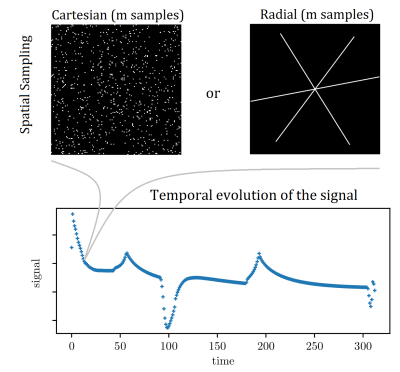

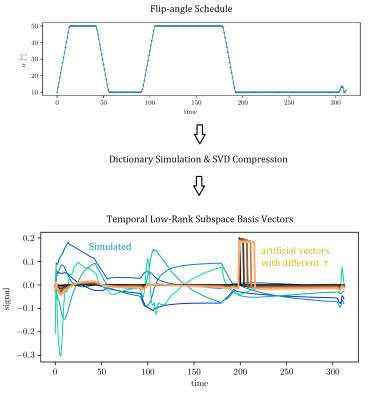

Two sampling patterns with equal numbers of k-space samples are compared: random points in the 2D plane (‘Cartesian’) and in-plane radial (golden angle), see Fig. 1. A realistic dictionary is obtained by EPG-simulation [7] of signals generated by the flip-angle schedule depicted in Fig. 2, and subsequent compression to rank six by SVD, also yielding the compression matrix L [2].Measured data is simulated with

$$y=UFSz\quad(1)$$

where $$$U$$$ is the undersampling matrix, $$$F$$$ the Fourier transform, $$$S$$$ the coil sensitivities, $$$y$$$ the measurements in the k-t domain, and $$$z$$$ the ground-truth vector in temporal image space. CG-SENSE [8] is employed for reconstruction

$$\min_x||UFSLx-y||\quad(2)$$

where $$$x$$$ is the temporally compressed image domain. A homogeneous disc phantom was employed in all experiments.

Robustness towards Systematic and Statistical Errors

‘Ideal’ measurements $$$y$$$ were generated with the same model as used for reconstruction (2) – assuming a ‘ground-truth’ where signals are linear combinations of temporal basis vectors, $$$z = L z_0$$$ where $$$z_0$$$ is the phantom in the compressed domain.

Systematic errors arise if true temporal behaviour isn't fully explained by such linear combination: $$$\nexists\;z_0\;:\;z=Lz_0$$$. Herein, $$$z$$$ was chosen from the uncompressed dictionary of signals.

Statistical errors were added through Gaussian noise in temporal k-space, with SNR = $$$10^4$$$, defined relative to the signal at k = 0.

These tests were performed using different amounts of data, quantified by the number of k-space samples obtained per magnetization state in the pulse cycle, see Fig. 1, where $$$m=$$$ number of samples acquired per state, which must be a multiple of $$$n=$$$ number of samples in one radial spoke. These $$$m$$$ samples will be distributed randomly for Cartesian patterns, but arranged into spokes for radial.

Additional to simulations, an equivalent in vivo brain scan with $$$m=2n$$$ was performed to support our results with experimental evidence. Relaxation time maps were derived from compressed components by dictionary matching [1].

Ability to reconstruct temporally localised components

Examining the interplay between sampling and temporal signal properties, we artificially changed one basis vector in $$$L$$$ to have most of its energy concentrated in a short time-frame $$$\tau$$$, see Fig. 2. This modified subspace was then used both as a forward model to generate data, and for reconstruction. By varying $$$\tau$$$, we observed how well this component can be reconstructed.

Results

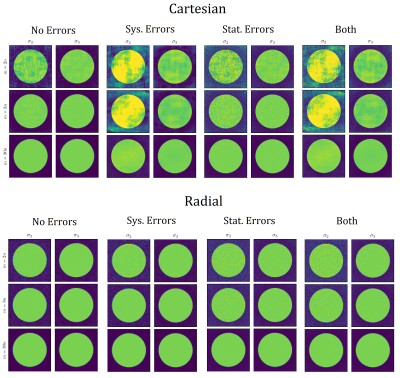

Robustness towards Systematic and Statistical ErrorsFig. 3 shows simulated reconstructions for increasing numbers of samples and different kinds of errors. Without errors present, radial sampling produces correct reconstructions from fewer samples than Cartesian, however, for the relatively small number of samples $$$m = 3n$$$, the Cartesian reconstruction is also quite accurate. When errors are added, Cartesian reconstructions with small numbers of samples give much greater errors than radial equivalents.

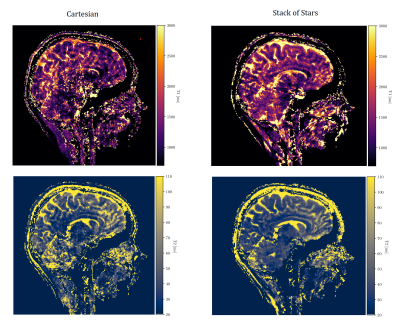

Fig. 4 displays in vivo results: stack of stars reconstructions show less aliasing

Ability to reconstruct temporally localised components

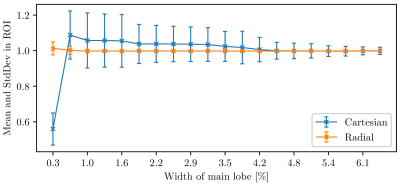

Fig. 5 shows that with radial sampling, the artificial component can be reconstructed consistently regardless of its duration $$$\tau$$$. In contrast, Cartesian sampling leads to large errors (and variance) for short $$$\tau$$$.

Discussion & Conclusions

This simulation study compared Cartesian and radial sampling schemes’ ability to reconstruct MRF time-series data in presence of errors, high degree of undersampling, and presence of short-lived temporal components.Reconstructions in presence of errors showed that radial sampling is more robust, potentially because oversampling k-space centre creates redundancy. Blurring, resulting from radial sampling, was not explored in our experiments yet, which considered only a large spatially homogeneous digital phantom.

In vivo experiments reflect simulation findings, despite the possibility of other sources of errors such as motion.

Simulations with artificial, highly localised temporal components showed that radial sampling is also better at reconstructing these. This result, while intuitive, is not clear mathematically from the temporal low-rank formulation [8], since all acquired samples contribute to every compressed temporal component. Furthermore, this suggests that it is relatively more important to use a radial (or similar) scheme for MRF sequences that produce short-lived, quickly varying signals; sequences producing smooth temporal variation on the other hand may benefit from more uniform sampling [9].

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by core funding from the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering [WT203148/Z/16/Z] and by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London and/or the NIHR Clinical Research Facility. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.References

[1] Dan Ma et al, Magnetic resonance fingerprinting, Nature 7440:187-192, Springer Science and Business Media, 2013, DOI: 10.1038/nature11971

[2] Debra McGivney et al, SVD Compression for Magnetic Resonance Fingerprinting in the Time Domain, IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging Vol.33/Num.12:2311-2322, IEEE, 2014, DOI:10.1109/tmi.2014.2337321

[3] Benjamin Marty et al, Quantitative Skeletal Muscle Imaging Using {3D} {MR} Fingerprinting With Water and Fat Separation, JMRI Vol.53/No.5:1529-1538, Wiley, 2022, DOI:10.1002/jmri.27381

[4] Olivier Jaubert et al, T1, T2 and Fat Fraction Cardiac MR Fingerprinting: Preliminary Clinical Evaluation, JMRI Vol.53/No.4:1253-1265, Wiley, 2020, DOI:10.1002/jmri.27415

[5] Jakob Asslaender et al, Pseudo Steady-State Free Precession for MR-Fingerprinting, MRM Vol.77/No.3:1151-1161, Wiley, 2016, DOI:10.1002/mrm.26202

[6] Martin Cloos et al, Rapid Radial T1 and T2 Mapping of the Hip Articular Cartilage With Magnetic Resonance Fingerprinting, JMRI, Vol.50/No.3, Wiley, 2018, DOI:10.1002/jmri.26615

[7] Matthias Weigel, Extended phase graphs: Dephasing, RF pulses, and echoes - pure and simple, JMRI, Wiley, 2014, DOI:10.1002/jmri.24619

[8] Jakob Asslaender et al, Low rank alternating direction method of multipliers reconstruction for MR fingerprinting, MRM, Wiley, 2017, DOI:10.1002/mrm.26639

[9] Yun Jiang et al, Fast 3D MR Fingerprinting with Pseudorandom Cartesian Sampling, ISMRM 2019, Abstract No. 1108

[10] David Leitao et al, Efficiency analysis for quantitative MRI of T1 and T2 relaxometry methods, Physics in Medicine & Biology, IOP Publishing, 2021, DOI:10.1088/1361-6560/ac101f

Figures

Figure 1: Top row: examples of employed k-space sampling patterns for individual magnetisation states in the 313 TRs long cycle, see Fig. 2 top row. The 'Cartesian' pattern is the phase-encoding plane of a 3D Cartesian scan (readout-direction perpendicular to paper-plane). The radial pattern is three golden-angle rotated spokes, which could be a single plane from a 3D ‘stack of stars’ trajectory.

Bottom row: example temporal signal, helping to clarify how sampling is spread out in the k-t domain.

Figure 2: Top row: flip-angle schedule, optimised by Cramer-Rao bound minimisation [10] (smoothness constraint and FA in [10°, 50°]). Preceding inversion pulse not shown.

Bottom row: orthonormal temporal compression basis vectors in shades of blue/green. Short lived, artificial basis vectors (tau = 0.3% … 6.4% of the pulse cycle) are shown in shades of orange (unnormalized for better visibility, but orthogonal to the blue ones). These do not follow from the flip-angle schedule in Fig. 1, but were used to investigate which sampling pattern can resolve rapidly varying components.

Figure 4: T1 and T2 maps of a consenting healthy volunteer (ethical approval HR-18/19-8700) scanned with our MRF

sequence at 7T (London

Collaborative Ultra-high field system, MAGNETOM Terra, Siemens, Erlangen,

Germany). 3D Cartesian reconstructions on the left and stack of stars

on the right. T1 maps are in the top, T2 in the bottom row. Overall quality is limited by high undersampling and the basic reconstruction technique employed (cf. [9]). This is experimental evidence for the superiority of stack of stars sampling in this specific MRF setup agreeing with simulated predictions.

Figure 5: Superior temporal resolution of the radial sampling pattern. The coordinate axis is showing the width of the artificial basis vector (orange in Fig. 2) relative to the length of the whole pulse cycle (length 313 TRs). The ordinate axis shows the mean (= 1 expected) and variation in a ROI inside the phantom. Radial does not deviate much from the expectation and exhibits low variation. Cartesian on the other fails to accurately resolve the shorter-lived temporal components.