2159

Habitat analysis by multi-parametric MRI predicts progressive white matter hyperintensities in cerebral small vessel disease1Radiology, Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, shanghai, China, 2Anesthesiology, Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, shanghai, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Vessels, Dementia

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) are commonly seen in cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) and are associated with an risk of cognitive impairment. However, the mechanism by which WMH develop is incompletely characterized. In this study, we conducted habitat analysis based on physiologic MRI parameters to investigate whether WMH habitat can predict progressive WMH in CSVD. We found that the physiologic MRI habitat with lower fractional anisotropy and cerebral blood flow, higher mean diffusivity, axial diffusivity and radial diffusivity was highly overlapping with the growing WMH in patients after one-year followup, and thus could predict progressive WMH in CSVD.Abstract

IntroductionCerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) is generally caused by disorders of the intrinsic cerebral arteriolar system1. CSVD is an important subtype of stroke and the major cause of dementia2. White matter hyperintensities (WMH) are the most common feature of CSVD on T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI3 with a prevalence up to 94% in the general population aged around 804. It is associated with cognitive decline, a 90% increased risk of dementia and a 200% increased risk of stroke5. WMH are often heterogeneous, for example, the volume of WMH may increase, remain stable, or even regress one year after a minor stroke6. The microstructures within WMH, including the integrity of neural fibers, the structure of small vessels and histopathology, might vary distinctly, causing the heterogeneity of WMH7. A habitat analysis on radiological imaging involves the definition of individualized descriptions of subregions within a heterogenous region of interest in a similar manner to the description of environmental habitats in ecology8. The use of a clustering method to group together similar voxels in a white matter habitat analysis could help to determine WMH heterogeneity and prognosis. In this study, we aimed to investigate whether WMH habitat on physiologic MRI can predict progressive WMH.

Methods

Multi-parametric T1-weighted and T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MR imaging, fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), axial diffusivity (AD), radial diffusivity (RD) and cerebral blood flow (CBF) were obtained from 69 CSVD patients and one-year followup, using a SignaHDxt 3T MRI scanner (GE Healthcare, United States). In detail, the preprocessed DWI data after denoising, Gibbs ringing removal, motion and eddy correction was fitted to DTI model, using FSL. And the CBF maps were calculated from the ASL-MRI data. WMH regions for the baseline and followup conditions were automatically identified from the corresponding FLAIR images. After linear coregistration between images of the baseline and followup, the whole WM area was segmented into four subregions including normal appearing WM (NAWM), constant WMH, growing WMH and shrinking WMH. Based on these physiologic parameters including FA, MD, AD, RD and CBF, habitat analysis was performed to distinguish growing WMH from NAWM, and also shrinking WMH from constant WMH for each patient, using the script of kmeans in Matlab. And the performance in predicting growing WMH and shrinking WMH was evaluated by the overlapping percentage of physiologic habitats and true WM subregions. The flowchart of the study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Results

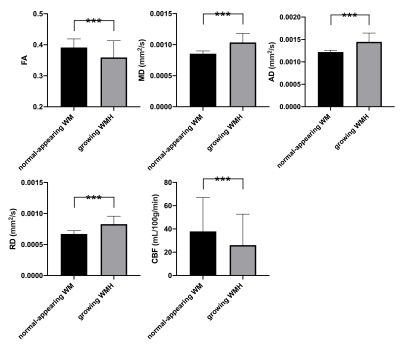

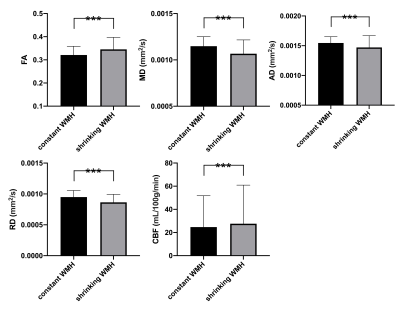

The demographic characteristics and clinical outcome of all patients are listed in Table 1. Compared to the baseline, the cognitive level of patients when one-year followup appeared not to significantly change using the paired t-tests for the rating scales of mini-mental state examination (MMSE) and Montreal cognitive assessment scale (MoCA; both p values > 0.5). After WM subtyping, all these five physiologic parameters including FA, MD, AD, RD and CBF showed significant differences between growing WMH and NAWM, and also between shrinking WMH and constant WMH (all p values < 0.001 after multiple comparison correction, Figure 2 and 3). When the number of clusters was set to two, the accuracy of the physiologic MRI habitat with lower FA and CBF, higher MD, AD and RD values was 88.9% ± 12.7% to distinguish growing WMH from NAWM, as well as with a sensitivity of 91.4% ± 13.5% and a specificity of 86.5% ± 12.3% (Table 2). When the number of clusters was changed to three, the corresponding accuracy decreased to 71.1% ± 8.9%. Moreover, the accuracies of the physiologic MRI habitat with higher FA and CBF, lower MD, AD and RD values was 76.6% ± 12.3% and 65.9% ± 9.3% to distinguish shringing WMH from constant WMH, when the number of clusters was set to two and three, respectively (Table 2).

Discussion & Conclusion

This study performed habitat analysis based on physiologic MRI captured in FA, MD, AD, RD and CBF to assess the risk WM regions and thus predict progressive WMH in CSVD. All these five physiologic parameters showed significant differences between growing WMH and NAWM, and between shrinking WMH and constant WMH. The accuracy of the habitat with lower FA and CBF, higher MD, AD and RD values was 88.9% ± 12.7% to distinguish growing WMH from NAWM. The results demonstrated that the habitat analysis on physiologic MRI could provide comprehensive and quantitative assessment of risk WM regions, and thus provide non-invasive and objective evidence for early intervention of subjects with CSVD.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by YG2022QN035, 82171885, 21TS1400700.References

1. Wardlaw J, Smith C, Dichgans M. Mechanisms of Sporadic Cerebral Small Vessel Disease: Insights from Neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:483-97.

2. Pantoni L. Cerebral Small Vessel Disease: From Pathogenesis and Clinical Characteristics to Therapeutic Challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:689-701.

3. Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, Cordonnier C, Fazekas F, Frayne R, et al. Neuroimaging Standards for Research into Small Vessel Disease and Its Contribution to Ageing and Neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:822-38.

4. Garde E, Mortensen EL, Krabbe K, Rostrup E, Larsson HB. Relation Between Age-Related Decline in Intelligence and Cerebral White-Matter Hyperintensities in Healthy Octogenarians: A Longitudinal Study. Lancet (London England). 2000;356:628-34.

5. Debette S, Markus HS. The Clinical Importance of White Matter Hyperintensities on Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Bmj. 2010;341:c3666.

6. Wardlaw J, Chappell F, Valdés Hernández M, Makin S, Staals J, Shuler K, et al. White Matter Hyperintensity Reduction and Outcomes After Minor Stroke. Neurology. 2017;89:1003-10.

7. Ter Telgte A, van Leijsen EMC, Wiegertjes K, Klijn CJM, Tuladhar AM, de Leeuw FE. Cerebral Small Vessel Disease: From a Focal to a Global Perspective. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:387-98.

8. Lee J, Narang S, Martinez J, Rao G, Rao A. Spatial habitat features derived from multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging data are associated with molecular subtype and 12-month survival status in glioblastoma multiforme. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136557.

Figures

Figure 1

Flowchart demonstrating the habitat analysis and model evaluation for each subject. After linear coregistration between images of the baseline and followup, the whole baseline WM area was segmented into four subregions including normal appearing WM (NAWM), constant WMH, growing WMH and shrinking WMH.

Figure 2

After WM subtyping, all these five physiologic parameters including FA, MD, AD, RD and CBF showed significant differences between growing WMH and NAWM.

Figure 3

After WM subtyping, all these five physiologic parameters including FA, MD, AD, RD and CBF showed significant differences between shrinking WMH and constant WMH.