2149

Probing arm muscle structure underlying motor impairment in children with cerebral palsy using DTI tractography1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, United States, 2Department of Physical Therapy and Human Movement Sciences, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States, 3Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States, 4Department of Neurology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Muscle, Diffusion Tensor Imaging, Cerebral Palsy

Individuals with cerebral palsy (CP) exhibit musculoskeletal maladaptations that have a profound impact on wrist and hand function, yet there is little understanding regarding underlying arm muscle structural changes. We implemented DTI to estimate in vivo muscle architecture of a forearm flexor muscle in both paretic and non-paretic arms of children with hemiparetic CP (n=5). Bone length, muscle size, fascicle lengths, and MD decreased while fascicle curvature increased in the paretic limb. Interlimb differences in fascicle length and curvature were correlated with interlimb differences in MD. We show that DTI is effective at capturing forearm muscle architecture changes in CP.

Introduction

Hemiparetic cerebral palsy (CP) results in progressive secondary musculoskeletal (MSK) changes in the affected (paretic) side of the body, which is particularly debilitating in wrist and hand function1. There are inconclusive findings regarding changes in fascicle geometry among previous diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) tractography studies in CP populations2,3, which focused on leg muscles. Furthermore, there has been no characterization of diffusivity changes in the affected arm muscles in CP, which may provide insight into pathological changes in muscle tissue. In this study, we implement DTI in hemiparetic CP (HCP) to probe muscle structural changes in the paretic flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) relative to the non-paretic FCU across three hierarchical levels: musculoskeletal, fascicular, and tissue levels. Additionally, muscle geometry and diffusivity estimates were compared to determine whether there was a relationship between macro- and micro-structural interlimb differences.Methods

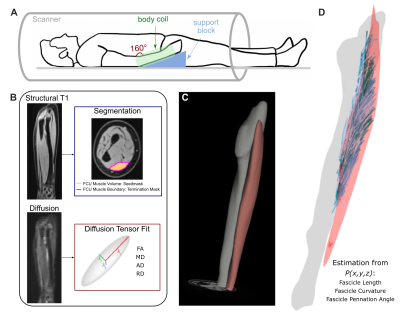

Image Acquisition and Pre-Processing: In five children with mild to moderate4 HCP (11.9±3.1y, 1F), MR images of both forearms were acquired using a 1.5T Siemens Aera scanner and a 2x18 channel body matrix coil. The arm was secured in an MRI-compatible orthoses (Fig.1A). T1-weighted 3D VIBE (TR=16ms,TE=7.16ms,FOV=256x304mm2,voxel=0.78x0.78x3mm3) and diffusion-weighted spin-echo EPI (TR=8500ms,TE=48ms,FOV=250x250mm2,voxel=1.25x1.25x6.5mm3), including 3x12 diffusion-weighted directions (b=400s/mm2) and 10 volumes with no diffusion weighting (b=0s/mm2), were acquired. Fat was suppressed with Spectral Attenuated Inversion Recovery. Processing of MR data was done in the FSL software library5. Diffusion tensors were fit at each voxel of the dMR volumes. T1 images were used to segment the FCU muscle volume and boundary (Fig.1B) and measure the FCU length and ulna bone length.DTI Tractography and Post-Processing: Probabilistic tractography was performed in FSL5. From each voxel in the seed region (the FCU muscle volume, Fig.1C), probabilistic tractography was performed bidirectionally (step size=0.5mm, turning angle threshold=90°) and terminated if exiting the FCU muscle region. In custom MATLAB codes, coordinates of raw tracts were fitted to second-order polynomial curves. Then, fascicle lengths (normalized to the ulna bone length), pennation angles, and curvature were estimated from the polynomial curves, and filtered by a predetermined set of anatomical constraints. Remaining curves represented valid fascicle representations used in further analyses (Fig.1D). Whole-volume diffusivity metrics were estimated by calculating fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD) within each voxel from its fitted diffusion tensor and averaged across the FCU volume.

Statistical Analyses: Two-sample t-tests were performed to determine significance of differences between the non-paretic and paretic arms in fascicle geometry measurements and diffusivity metrics. Interlimb difference ratios were calculated for each of the geometry and diffusivity estimates by dividing the average value in the paretic limb by the average value in the non-paretic limb. Pearson correlations were calculated between the interlimb difference ratios for fascicle measurements and diffusivity metrics.

Results

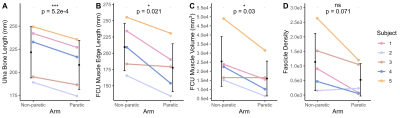

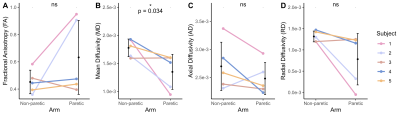

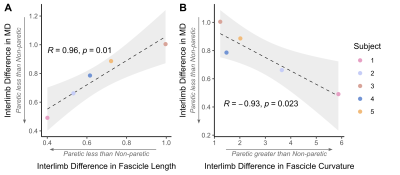

The bone length, muscle length, and muscle volume (p<0.05) (Fig.2A-C) significantly decreased in the paretic arm relative to the non-paretic arm. Fascicle count also decreased but did not reach significance (p=0.071) (Fig.2D). Even after normalizing for shorter ulna bones, fascicle length was decreased in the paretic arm (p=0.04) (Fig.3A), while fascicle curvature was increased in the paretic arm (p=0.038) (Fig.3B) and pennation angle showed no difference (Fig.3C) relative to the non-paretic arm.Across the study cohort, whole-volume MD was significantly decreased in the paretic arm’s FCU as compared to the non-paretic arm’s FCU (p=0.034) (Fig.4B), while whole-volume FA, AD, and RD values were not different between arms (Fig.4A,C,D). Finally, there were significant correlations between geometry estimates and diffusivity metrics. Specifically, interlimb differences in MD were positively correlated with interlimb differences in fascicle length (R=0.96,p=0.01) (Fig.5A) and negatively correlated with interlimb differences in fascicle curvature (R=-0.93,p=0.023) (Fig.5B).

Discussion

In children with HCP, DTI estimates show that overall MSK parameters (bone length and muscle size) were reduced in the paretic arm, due to the disrupted development of the MSK system from birth6. At the fascicle level, even after accounting for altered bone size, the paretic FCU showed shorter fascicles and higher curvature than the non-paretic FCU, which would reduce the amount of force translated to the bone and ultimately negatively affect the muscle’s force-generating capacity7,8.The paretic FCU also showed decreased MD as compared to the non-paretic FCU, which indicates possible fibrosis and proliferation of surrounding extracellular matrix9. Additionally, results showed that as the paretic muscle MD decreased, the paretic muscle fascicle length decreased and fascicle curvature increased with respect to the non-paretic limb. This relationship suggests that muscle macrostructural (at the fascicle level) and microstructural (at the tissue level) adaptations are linked colinearly. In combination with the reduced size of the overall MSK unit, these alterations would reduce a paretic muscle’s contraction levels9,10 and negatively impact its passive properties11 over time, exacerbating muscle weakness and stiffness in individuals with CP.

This study, for the first time, implements DTI to characterize arm muscle architecture that underlies wrist and hand dysfunction in CP. Even when normalizing to a within-subject control, there were consequential and correlated interlimb differences across the muscle’s structural levels. Results establish that DTI is effective at probing changes in forearm muscle architecture in children with CP, and can be leveraged to identify imaging biomarkers for MSK adaptations in CP.

Acknowledgements

This work was done in part with the support of NIH grants R01NS058667, and predoctoral training fellowships T32EB009406 to AH and F31HD110236 to DJ. We thank Marie Wasielewski and Donny Nieto for their assistance in MR imaging.

References

- Graham HK, Selber P. Musculoskeletal aspects of cerebral palsy. J Bone Jt Surg - Ser B 2003;85:157–66. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.85B2.14066.

- Sahrmann AS, Stott NS, Besier TF, Fernandez JW, Handsfield GG. Soleus muscle weakness in cerebral palsy: Muscle architecture revealed with Diffusion Tensor Imaging. PLoS One 2019;14:e0205944. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205944.

- D’souza A, Bolsterlee B, Lancaster A, Herbert RD. Muscle architecture in children with cerebral palsy and ankle contractures: an investigation using diffusion tensor imaging. Clin Biomech 2019;68:205–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2019.06.013.

- Yam WKL, Leung MSM. Interrater reliability of modified ashworth scale and modified tardieu scale in children with spastic cerebral palsy. J Child Neurol 2006;21:1031–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/7010.2006.00222.

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Johansen-Berg H, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 2004;23:208–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051.

- Mathewson MA, Lieber RL. Pathophysiology of Muscle Contractures in Cerebral Palsy 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2014.09.005.

- Muramatsu T, Muraoka T, Kawakami Y, Shibayama A, Fukunaga T. In vivo determination of fascicle curvature in contracting human skeletal muscles. J Appl Physiol 2002;92:129–34. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.2002.92.1.129.

- Handsfield GG, Williams S, Khuu S, Lichtwark G, Stott NS. Muscle architecture, growth, and biological Remodelling in cerebral palsy: a narrative review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022;23:. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12891-022-05110-5.

- Berry DB, Regner B, Galinsky V, Ward SR, Frank LR. Relationships between tissue microstructure and the diffusion tensor in simulated skeletal muscle. Magn Reson Med 2018;80:317–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.26993.

- Malis V, Sinha U, Csapo R, Narici MV, Smitaman E, Sinha S. Diffusion tensor imaging and diffusion modeling: Application to monitoring changes in the medial gastrocnemius in disuse atrophy induced by unilateral limb suspension. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019;49:1655–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/JMRI.26295.

- Lieber RL, Fridén J. Muscle contracture and passive mechanics in cerebral palsy. J Appl Physiol 2019;126:1492–501. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.00278.2018

Figures

Figure 1. (A) Subject positioning in 1.5T MR scanner with 2x18 channel body coil around lower arm. (B) MR data preprocessing, including segmentation from T1 images and diffusion tensor estimation from dMR volumes. (C) Example of segmented ulna bone and FCU muscle in T1 image. (D) Examples of reconstructed fascicles, after tracts are fit to 2nd order polynomial curves and filtered by anatomical constraints, from which fascicle length, curvature, and pennation angles are estimated.

Figure 2. (A) Length of the ulna bone (mm). (B) Length of the edge of the FCU muscle (mm). (C) Volume of the FCU muscle (mm3). (D) Fascicle count (number of reconstructed fascicles remaining after fitting and constraints) in the FCU muscle. (A)-(D): Mean values for each subject (n=5) for the non-paretic and paretic arms are shown in color. Mean and standard deviation across all subjects in each arm are shown in black. P-values represent significance of two sample t-tests performed on data grouped by arm. A * indicates p<0.05, and a *** indicates p<0.001.

Figure 3. (A) Lengths of reconstructed fascicles in the FCU muscle, normalized to the ulna bone length in each subject. (B) Curvature of reconstructed fascicles in the FCU muscle, normalized to the corresponding estimated fascicle length. (C) Pennation angles of reconstructed fascicles in the FCU muscle. (A)-(C): Median and interquartile range for each subject (n=5) for the non-paretic and paretic arms are shown. P-values represent significance of two sample t-tests performed on data grouped by arm. A * indicates p<0.05.

Figure 4. (A) Fractional anisotropy (FA) across the FCU muscle. (B) Mean diffusivity (MD) across the FCU muscle. (C) Axial diffusivity (AD) across the FCU muscle. (D) Radial diffusivity (RD) across the FCU muscle. (A)-(D): Mean values for each subject (n=5) for the non-paretic and paretic arms are shown in color. Mean and standard deviation across all subjects in each arm are shown in black. P-values represent significance of two sample t-tests performed on data grouped by arm. A * indicates p<0.05.

Figure 5. (A) Interlimb difference in MD versus interlimb difference in fascicle length. (B) Interlimb difference in MD versus interlimb difference in fascicle curvature. (A)(B): Interlimb differences are calculated such that: if equal to 1, Paretic=Non-paretic; if greater than 1, Paretic > Non-paretic; if less than 1, Paretic < Non-paretic. Individual interlimb difference values for each subject (n=5) are shown in color. Pearson correlation coefficient R and resulting p-value are shown with fitted regression (black dashed line) and confidence interval (light grey).