2148

On the MRI Signature of Healed Juvenile Osteochondritis Dissecans (JOCD) in the Knee – The ‘Scar Sign’1Radiology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States, 2CMRR/Radiology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States, 3Orthopedics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States, 4University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Bone, Adolescents, Epiphyseal Cartilage, Juvenile Osteochondritis Dissecans

Healing of Juvenile Osteochondritis Dissecans requires progressive lesion ossification and osseous bridging with the parent bone. The ‘Scar Sign’ is an MR imaging finding that documents a healed knee JOCD lesion and is characterized by a distinct hypointense line at the prior lesion – parent bone interface, best identified on PD- or T1-weighted images w/o FS on routine clinical MRI. Knowledge of stages, timeline of healing and expected MR imaging findings of JOCD is important for the reporting Radiologist. It will facilitate prognostication and can serve as a reliable outcome measure for future research on evidence based Juvenile Osteochondritis Dissecans management.Summary of Main Findings

1. In the retrospective study of 101 consecutive JOCD knees, a total of 12 ‘Scar Signs’ (rate 11.9%) were independently identified by two Board Certified MSK-Radiologists. No ‘Scar Sign’ was identified in the closely age and sex matched 101control knees. The ‘Scar Sign’ rates did statistically differ between the JOCD knees and the control knees (p-value = 0.0002 from the one-sided Fisher’s exact test) confirming that the 'Scar Sign' is specific to JOCD.2. Healing of Juvenile Osteochondritis Dissecans requires progressive lesion ossification and osseous bridging with the parent bone. ‘Scar Sign’ on MRI documents a healed knee JOCD lesion and is characterized by a distinct hypointense line at the prior lesion – parent bone interface, best identified on PD- or T1-weighted images w/o FS on routine clinical MRI.

3. The natural history of JOCD healing is documented for a subset of ‘Scar Signs’ in all study group patients with available prior comparison MRI’s. This data set provides longitudinal evidence on the epiphyseal cartilage origin and subsequent endochondral ossification of JOCD lesions during the healing process.

Introduction

Juvenile Osteochondritis Dissecans (JOCD) of the knee is a developmental disease preferentially affecting highly active children and adolescents that may heal in a predictable sequence of events or, conversely, become unstable and lead to premature osteoarthritis [1]. There is abundant literature on the MRI findings of unstable JOCD lesions [2, 3]. JOCD healing has been described on X-rays [4, 5], however, little is known about the sequential MRI findings of healing JOCD lesions. There is a lack knowledge in the professional community on new insights into the natural history of JOCD and unfortunately, it remains common belief that JOCD is caused by an osseous fragment that detaches from the underlying bone [6]. New scientific evidence, however, demonstrates that lesions originate from a delay in the ossification during development with an area of epiphyseal cartilage necrosis [7]. Healing of JOCD requires progressive ossification of the epiphyseal cartilage lesion and osseous bridging with the parent bone [8]. The purpose of this retrospective study is to enable accurate radiology reporting on a specific finding of healed JOCD lesions, the 'Scar Sign', and facilitate better understanding of the natural history of the disease.Materials and Methods

This is an IRB approved, HIPPA compliant retrospective review from a single institution. 199 consecutive clinical knee MRI’s for JOCD ordered between 6/09/2008 and 09/23/2021. The inclusion criteria were met by 101 MRI studies of 76 patients (25 females, 51 male) between 5 and 25 years of age. The control studies consisted of 101 knee MRI’s of closely age matched patients that were ordered for other pathologies. Two Board Certified MSK-Radiologists performed an independent review to evaluate for the presence of the ‘Scar Sign’. A Fisher exact test was performed for statistical analysis.Magnetic Resonance Imaging:All knee MRIs were acquired either on a 3T or 1.5T MRI instrument (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) at our institution using an eight-channel receive coil or a 15-channel transmit-and-receive knee coil (QED). In both groups, a clinical routine multiplanar, multisequence knee MRI protocol was utilized: sagittal proton density (PD) - weighted TSE w/o fat-suppression (FS), sagittal PD-weighted TSE (w FS), coronal T1-weighted TSE (w/o FS), coronal T2-weighted TSE (w FS), axial T1-weighted TSE w/o FS.The MRI ‘Scar Sign’ was defined as: i) a hypointense line at the parent bone and progeny lesion interface on PD- or T1-weighted MR images w/o FS at the expected predilection site of JOCD and ii) no significant bone marrow edema (Fig.1) on PD – or T2-weighted MR images w FS.Results and Discussion

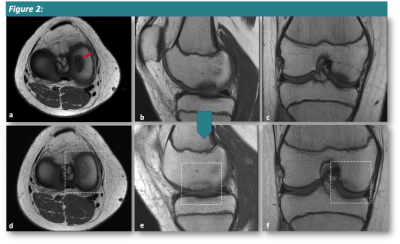

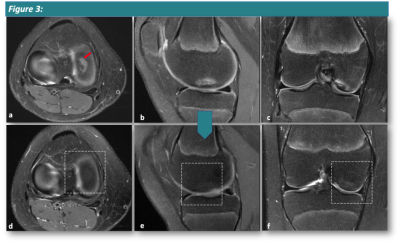

The ‘Scar Sign’ on MRI documents a healed knee JOCD lesion and is characterized by a distinct hypo-intense line at the prior lesion – parent bone interface, best identified on PD- or T1-weighted images w/o FS on routine clinical MRI (Fig. 2). In the retrospective study of 101 consecutive JOCD knees, a total of 12 ‘Scar Signs’ (rate 11.9%) were independently identified by two Board Certified MSK-Radiologists. No ‘Scar Sign’ was identified in the closely age and sex matched 101control knees. The ‘Scar Sign’ rates did statistically differ between the JOCD knees and the control knees (p-value = 0.0002 from the one-sided Fisher’s exact test) confirming that the scar sign is specific to JOCD. All patients with the ‘Scar Sign’ were free of symptoms. Healing of JOCD lesions requires progressive ossification of the cartilaginous progeny lesion, osseous bridging with the parent bone and lastly the reconstitution of normal bone marrow in both the progeny and parent bone [8, 9]. Resolution of any residual edema on T2-weighted images and normal fatty marrow on T1-weighted images (Fig. 2 and 3) is in keeping with the reconstitution of original trabecular architecture that allows repopulation of normal bone marrow. This is also known from the final stage of fracture healing [10]. The failure rate of healing after non-operative treatment reported varies, radiographic healing was reported to be as high as 76%. Therefore, knowledge of stages, timeline of healing and expected imaging findings on MR is important for the reporting Radiologist, facilitates prognostication, and can serve as a reliable outcome measure for future research on evidence based Juvenile Osteochondritis Dissecans management.Acknowledgements

Sources of Funding: NIH/NIAMS R01 AR070020 – Novel MRI Methods for Osteochondritis Dissecans (OCD) / Osteochondrosis (OC)Acknowledgement: Statistical support Dr. Lin Zhang, University of Minnesota.References

1. Chau, M.M., et al., Osteochondritis Dissecans: Current Understanding of Epidemiology, Etiology, Management, and Outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2021. 103(12): p. 1132-1151.

2. Kijowski, R., et al., Juvenile versus adult osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: appropriate MR imaging criteria for instability. Radiology, 2008. 248(2): p. 571-8.

3. Zbojniewicz, A.M. and T. Laor, Imaging of osteochondritis dissecans. Clin Sports Med, 2014. 33(2): p. 221-50.

4. Parikh, S.N., et al., The reliability to determine "healing" in osteochondritis dissecans from radiographic assessment. J Pediatr Orthop, 2012. 32(6): p. e35-9.

5. Wall, E.J., et al., The Reliability of Assessing Radiographic Healing of Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee. Am J Sports Med, 2017. 45(6): p. 1370-1375.

6. Bruns, J., M. Werner, and C. Habermann, Osteochondritis Dissecans: Etiology, Pathology, and Imaging with a Special Focus on the Knee Joint. Cartilage, 2018. 9(4): p. 346-362.

7. Ellermann, J., et al., Insights into the Epiphyseal Cartilage Origin and Subsequent Osseous Manifestation of Juvenile Osteochondritis Dissecans with a Modified Clinical MR Imaging Protocol: A Pilot Study. Radiology, 2017. 282(3): p. 798-806.

8. Kajabi, A.W., et al., Longitudinal 3T MRI T2 * mapping of Juvenile osteochondritis dissecans (JOCD) lesions differentiates operative from non-operative patients-Pilot study. J Orthop Res, 2022.

9. Olstad, K., S. Ekman, and C.S. Carlson, An Update on the Pathogenesis of Osteochondrosis. Vet Pathol, 2015. 52(5): p. 785-802.

10. Morgan, E.F., A. Giacomo, and L.C. Gerstenfeld, Overview of Skeletal Repair (Fracture Healing and Its Assessment). Methods Mol Biol, 2021. 2230: p. 17-37.

Figures

Figure 1: The ‘Scar Sign’ of healed JOCD

MR image on the left depicts the hypointense line on coronal T1-weighted TSE imaging w/o FS. The line is located at the healed interface of the parent bone and progeny lesion. Prior MR imaging had documented a JOCD lesion in this expected location at the medial femoral condyle.

Figure 2:

Completely Healed ‘Scar Sign’ on PD-weighted TSE sequence w/o FS. MRI of 12-year-old female patient at initial presentation (upper row: a, b, c) with JOCD lesion at the medial femoral condyle. The entire lesion is hypointense when compared to normal fatty marrow indicating that fatty marrow remains absent within an ossified lesion. Follow-up MRI, 7.5 months later (lower row: d, e, f) revealed stage IV healed lesion that has nearly completely resolved with a residual subtle hypointense line at the prior lesion and parent bone interface.

Figure 3:

T2-weighted TSE sequence w FS of same 12-year-old patient from Fig. 2 at initial presentation (upper: a, b, c) revealed JOCD lesion of the medial femoral condyle with bone marrow edema at the lesion interface. A rim of edema is noted proximal and distal to the interface, in the parent bone and in the lesion, respectively. On follow-up MRI, 7.5 months later (lower: d, e, f) completely healed JOCD lesion with resolved bone marrow edema is noted in keeping with restoration of normal trabecular bone architecture and marrow space in the final phase of healing.