2142

Heterogeneous distribution of hepatic and pancreatic fat fraction in overweight or obese children and adolescents1College of Biomedical Engneering & Instrument Science, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2MR Collaboration, Siemens healthineers Itd, Shanghai, China, 3Department of Radiology, Zhejiang University School of Medicine Children's Hospital Binjiang Campus Pediatrics, Hangzhou, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Fat

The ectopic fat is not evenly distributed in organs and can be a time dependent process that starts at early age. In this work, we focused on obese or overweight children and adolescents and calculated the voxel-wised liver and pancreas fat fraction. With our recently proposed deep learning method, we separately quantified the fat depositions in different compartments of liver and pancreas with high precisions. Our analysis revealed an unevenly distributed ectopic fat in both liver and pancreas at young age and suggested that hepatic and pancreatic fat depositions are weakly coupled but have different underlying mechanisms.Introduction

Overweight and obesity are major risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in both adults and children1. Along with fat accumulation, NAFLD may further develop to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and is tightly associated with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease2. Similarly, the fat deposition in the pancreas is termed as nonalcoholic fatty pancreas disease (NAFPD) and it also tightly links to some other diseases3. Ectopic fat in liver and pancreas may be heterogeneously distributed4-6. Biopsy and MRS are used as the gold standard for fat quantification and diagnosis, but are accompanied with relatively high sampling errors which will lead to inconsistent diagnostic results7,8. This study utilized an established deep learning method9 to automatically obtain three-dimensional hepatic and pancreatic maps of fat deposition on dual-echo T1W MR Images. The distribution of fat fraction in the liver and pancreas and the associations between fat deposition and biochemical measurements were also studied.Methods

Study subjects: 81 obese or overweight children and adolescents (Male/Female = 57/24, age = 11.6 ± 1.8 years-old) were enrolled.MRI Examination: All experiments were conducted on Philip 1.5 T MRI scanner with a dS TorsoCardiac Coil. A dual echo T1W sequence (mDIXON) was used for data acquisition. Acquisition parameters were: TR = 6.7 ms, TE = 1.93 ms and 4.00 ms, flip angle = 10 °, FOV = 380 × 380 mm2 or 450 × 450 mm2, slice thickness = 1.7-3.0 mm.

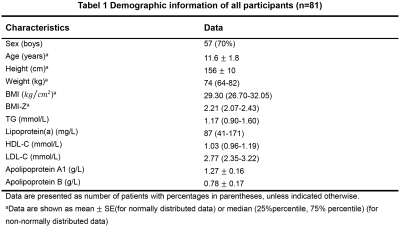

Laboratory test: Blood was sampled on each subject in fasting state and biochemical tests are listed in Table 1.

Data processing: The MRI images were segmented using a previously trained 3D nnU-Net model. Any large vessels and connective tissues remained in the liver mask were individually inspected and corrected if necessary. Pixel-wised fat fraction (FF) was calculated as: $$FF = \frac{fat}{fat+water}\times100\%$$ and the whole liver fat fraction (WLFF) and whole pancreas fat fraction (WPFF) were computed. The sub-organic distribution of ectopic fat were assessed by automatic segmenting liver into left and right liver compartments, as well as segmenting pancreas into head, body and tail compartments.

Statistical Analyses: All subjects were assigned to four levels based on their WLFF according to an established criterion10. Paired t-test, Wilcoxon rank sum test and spearman correlation analysis were applied accordingly to compare the fat accumulation in different sub-organic compartments, and to assess the correlation between fat deposition and biochemical parameters. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

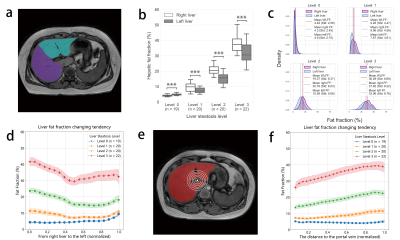

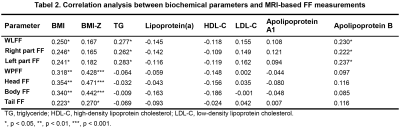

Table 1 summarizes the demographic information of all subjects. Pancreatic fat distributions were summarized in Figure 1. Compared with pancreas body and tail, pancreas head had less but a more uniformly distributed lipid deposition. In liver, fat deposition in the right was significantly higher than the left, except for level 0 of steatosis. The variances of liver fat distribution increased with liver steatosis levels (Figure 2c). In Figure 2d, liver FF was plotted against the distance from the right to left end and the fat was more deposited in the two ends than the middle. Using the hepatic portal vein as an anchor (Figure 2e), it can be clearly seen that fat accumulated as the distance to the portal vein increased (Figure 2f).Table 2 summarizes the correlation between the biochemical tests and FF measurements. BMI (BMI-Z) showed weak correlations with FF measures in liver but stronger associations in pancreas. Contrarily, in liver FF measures were all correlated with blood triglyceride and apolipoprotein B levels, which were not observed in pancreas.

Discussion

In this work, spatial distributions of ectopic fat in liver and pancreas were assessed automatically with a previously established model. Compared with manual selected ROI and single voxel MRS, this method is more efficient and unbiased, providing a more comprehensive assessment of ectopic fat deposition. The statistical analysis showed that the pancreatic fat accumulation was heterogeneous, lower fat content in pancreas head than in pancreas body and tail, which was consistent with a previous report6. In liver, the right compartment contained more fat than the left, which was also reported in other studies4,5. This could be attributed to the unbalanced nutrient supply between the two lobes11. We also found that the liver fat was more accumulated if more distant from the portal vein, which suggested that liver fat deposition might be influenced by its vascular system. However, there appears to be a weak association between the pancreatic and hepatic fat depositions (data not shown). This weak connection was echoed by the correlation analysis between the MRI-measured FF and laboratory biochemical tests, which inferred that hepatic and pancreatic fat depositions could be similarly related to obesity but bind to different underlying mechanisms.Conclusion

In young obese patients, the hepatic and pancreatic fat distribution is not uniform. The fat accumulates more in the right liver than the left, and more in the pancreas body and tail than the head. The hepatic fat accumulates more according to the distance to the portal vein. The pancreatic and hepatic FF measures have different correlations to biochemical tests. This work demonstrates a brief exploration into the fat distribution in the liver and pancreas in early obesity while further investigations are demanded.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1.Li ZZ, Xue J, Chen P, Chen LZ, Yan SP, Liu LY. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mainland of China: A meta-analysis of published studies. J Gastroen Hepatol 2014;29:42-51. Pierantonelli I, Svegliati-Baroni G. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Basic Pathogenetic Mechanisms in the Progression From NAFLD to NASH. Transplantation 2019. 103(1):e1-e13.

2.Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastro Hepat 2018;15:11-20.

3.Majumder S, Philip NA, Takahashi N, Levy MJ, Singh VP, Chari ST. Fatty Pancreas: Should We Be Concerned? Pancreas 2017;46:1251-1258.

4.Bonekamp S, Tang A, Mashhood A, Wolfson T, Changchien C, Middleton MS, Clark L, Gamst A, Loomba R, Sirlin CB. Spatial distribution of MRI-determined hepatic proton density fat fraction in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2014; 39(6):1525-1532.

5.Hua B, Hakkarainen A, Zhou Y, Lundbom N, Yki-Järvinen H. Fat accumulates preferentially in the right rather than the left liver lobe in non-diabetic subjects. Digestive and Liver Disease 2018; 50(2):168-174.

6.Triay BA, Aljabar P, Ridgway GR, Brady M, Bulte DP. Pancreas MRI Segmentation Into Head, Body, and Tail Enables Regional Quantitative Analysis of Heterogeneous Disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 2022;56:997-1008.

7.Ratziu V, Charlotte F, Heurtier A, et al. Sampling variability of liver biopsy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2005;128:1898-1906.

8.van Werven JR, Hoogduin JM, Nederveen AJ, et al. Reproducibility of 3.0 Tesla magnetic resonance spectroscopy for measuring hepatic fat content. J Magn Reson Imaging 2009;30:444-448.

9.Lin D, Wang Z, Li H, et al. Automated Measurement of Pancreatic Fat Deposition on Dixon MRI Using nnU-Net. J Magn Reson Imaging 2022.

10.Kuhn JP, Meffert P, Heske C, Kromrey ML, Schmidt CO, Mensel B, Volzke H, Lerch MM, Hernando D, Mayerle J, Reeder SB. Prevalence of Fatty Liver Disease and Hepatic Iron Overload in a Northeastern German Population by Using Quantitative MR Imaging. Radiology 2017; 284(3):706-716.

11.Gates GF, Dore EK. Streamline flow in the human portal vein. J Nucl Med 1973;14:79-83.

Figures