2134

Identification of NF2 loss in meningiomas using T2-weighted MRI and Deep Learning1Institute of Biomedical Engineering, Bogazici University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2Brain Tumor Research Group, Acibadem University, Istanbul, Turkey, 3Department of Medical Pathology, Acibadem University, Istanbul, Turkey, 4Department of Biomedical Engineering, Acibadem University, Istanbul, Turkey, 5Department of Neurosurgery, Acibadem University, Istanbul, Turkey, 6Department of Radiology, Acıbadem University, Istanbul, Turkey

Synopsis

Keywords: Tumors, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Deep Learning

NF2-L in meningiomas is a relevant indicator of prognosis. NF2-L is one of the most common genetic mutations in meningiomas. As a result of that situation, developing a non-invasive approach may assist the current clinical procedures. To our knowledge, some studies try to predict NF2-L using MRI modalities but either they use registration or performed using the modalities of MRI that are not in default MRI scanning procedures. Hence, the solutions that they provide are not clinically feasible. In this study, we aim to develop new approaches that are capable to implement directly into clinical procedures.[1]Summary of Main Findings

We achieved up to 87% (sensitivity: 82%, specificity: 91%) of accuracy on the test set using SSA metric. In contrast to this relatively high accuracy, we achieved a 72% accuracy (sensitivity: 56%, specificity: 81%) using MV and 65% accuracy (sensitivity: 63%, specificity: 72%) using the classical accuracy metric.Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 2 loss (NF2-L) in meningiomas is an indicator of a bad prognosis and increases death risk by 2.5 times [1]. In recent years using genetic information to understand underlying tumor biology became more popular. In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) updated the classification protocol for central nervous system tumors, and this update included some genetic mutations [2]. Furthermore, these genetic biomarkers have gained importance in the current clinic diagnosis procedures to diagnose brain tumors and more accurately predict tumor biology, individual diversity, treatment responses, relapse patterns, and survival rates [3-6]. Thus, clinicians increasingly use genetic biomarkers in determining treatment [7]. In this study, we propose a model to predict NF2-L non-invasively using T2-weighted MRI.Methods

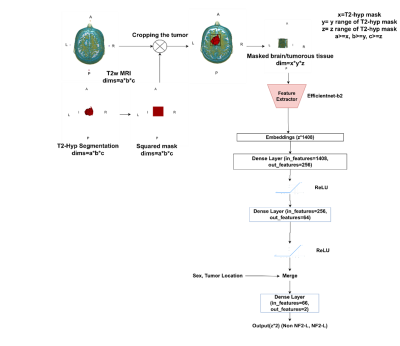

One hundred thirteen meningioma patients (36M/77F, mean age: 52.02±13.73 years, range: 18-86 years, 57 NF2-L positive and 56 NF2-NL) were retrospectively included in this IRB approved study. The patients were scanned using a brain tumor imaging protocol that included T2w MRI (TR=5000ms, TE=105ms) on a 3T clinical MR scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). NF2-copy number loss was determined by digital droplet PCR using pre-validated Taq-man probes. The hyperintense tumor region was manually segmented on T2w MRI using Slicer version 4.8.1 [8], and a cropped region of all the slices containing the tumor were used as the inputs to the deep learning models. A block diagram of the study pipeline is shown in Figure 1. In this study, a hybrid model was defined, in which pre-trained efficientnet-b2 (chosen by hyperparameter optimization among the models listed above) architecture was used as a feature extractor followed by a classifier produced in this study. For the preprocessing min-max normalization was used. Regularization and image augmentation methods, such as rotation, vertical/horizontal flipping, and random erasing were implemented to overcome the overfitting problem. For enhancing the result and reaching the global minima we performed hyperparameter optimization using Weight and Biases (wandb) [9]. Lastly, we add sex (1-male, 0-female) and tumor location as extra features to provide our model relevant features. Table 1 shows the hyperparameters of the proposed model, which were determined by wandb while maximizing the validation accuracy. Three different metrics, which were the majority voting (MV), single slice positivity, and slice-wise, were implemented to assign a final NF2-L status to the patients, which were then used to calculate the model accuracy. Majority voting was defined as,out label=(1/N∑i=0-N argmax(output_i))>0.5 ,

where output (N*c) is the two-class model output, N is the number of slices for a given patient, the target is the ground truth class for NF2-L (1 or 0), and the out label (1 or 0) is the result of the model for a given patient by taking into account all the slices. The single slice positivity was defined as,

out label= max(argmax(output)),

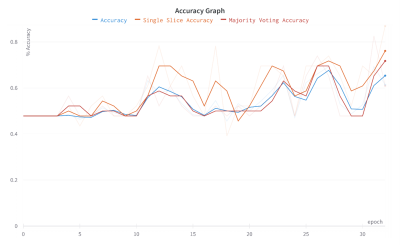

which assigns 1 to the output label even if one of the slices is marked as positive for a given patient. In the slice-wise metric, each slice is treated independently, and its NF2 status is assigned as a result of the model. Finally, the accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of the deep learning model are calculated to assess its performance. RESULTS We achieved to 87% (sensitivity: 82%, specificity: 91%) on SSA and 72% accuracy (sensitivity: 56%, specificity: 81%) on MV. We achieved 65% of accuracy (sensitivity: 63%, specificity: 72%) using the slice wise accuracy metric. Efficientnet-b2 was the most successful feature extractor among the all pre-trained models.

Results

We achieved to 87% (sensitivity: 82%, specificity: 91%) on SSA and 72% accuracy (sensitivity: 56%, specificity: 81%) on MV. We achieved 65% of accuracy (sensitivity: 63%, specificity: 72%) using the slice-wise accuracy metric. Efficientnet-b2 was the most successful feature extractor among the all pre-trained models.Discussion and Conclusion

We will contribute an algorithm to the literature that can predict NF2-L at the presurgery point. Prediction before surgery is crucial for treatment performance and even determining treatment type. The biopsy has many risks of complications that can occur in all surgical operations. Due to the risk of infection, possible damage to the surrounding tissue, etc. biopsy should be replaced with a more innovative approach. This can be a leading study to change the way of invasive trends to non-invasive ones.Acknowledgements

This study has been supported by TUBITAK 1001 grant 119S520.References

1. Baser, M.E., et al., Evaluation of clinical diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis 2. Neurology, 2002. 59(11): p. 1759.

2. Louis, D.N., et al., The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathologica, 2016. 131(6): p. 803-820.

3. Eckel-Passow, J.E., et al., Glioma Groups Based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT Promoter Mutations in Tumors. New England Journal of Medicine, 2015. 372(26): p. 2499-2508.

4. Goutagny, S., et al., Long-term follow-up of 287 meningiomas in neurofibromatosis type 2 patients: clinical, radiological, and molecular features. Neuro-Oncology, 2012. 14(8): p. 1090-1096.

5. Killela, P.J., et al., Mutations in IDH1, IDH2, and in the TERT promoter define clinically distinct subgroups of adult malignant gliomas. Oncotarget, 2014. 5(6): p. 1515-1525.

6. Labussière, M., et al., Combined analysis of TERT, EGFR, and IDH status defines distinct prognostic glioblastoma classes. Neurology, 2014. 83(13): p. 1200.

7. Tong, Z., et al., In vivo quantification of the metabolites in normal brain and brain tumors by proton MR spectroscopy using water as an internal standard. Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 2004. 22(5): p. 735-742.

8. Fedorov, A., et al., 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magnetic resonance imaging, 2012. 30(9): p. 1323-1341.

9. Biewald, L.J.S.a.f.w.c., Experiment tracking with weights and biases, 2020. 2(5).