2084

Subclinical vascular damage is associated with cognitive decline in middle-to-old age community subjects with high vascular risks1Department of Radiology, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China, 2The Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Vessels, fMRI (resting state)

Due to the insidious development of vascular degeneration, assessing subclinical vascular changes in people at high risks may aid early detection and intervention. We explored the relationship between the subclinical vascular function changes and vascular risks, vascular imaging markers, and cognition in a middle-to-old age community cohort. We found that larger vascular contractility in the intracranial arteries was related to younger age, less lacune, and better cognition. Participants with diabetes had a longer blood transit time from the ICAs to the capillary. These results suggested that subclinical vascular imaging markers were associated with brain parenchymal damage and cognitive decline.Introduction

Cerebrovascular health is crucial for maintaining brain function during aging. Due to the insidious development of vascular degeneration, these downstream parenchymal markers with presumed vascular origin1, 2 (white matter hyperintensity, WMH, lacunes, etc.) might not be able to timely reflect the state of vascular injury3. Several new ways to explore the spontaneous low-frequency fluctuations (sLFOs, <0.1Hz) in cerebral vasculature by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)3 may help us to understand the vascular health. SLFOs4 is originated from the endogenous fluctuations in the vascular tone, which could travel along thecerebral vasculature. According to previous studies5, 6, the time shift of propagation of sLFOs through the different vascular regions was interpreted as blood transit time, whose abnormal delay was related to cerebral hemodynamic impairment7, 8. SLFOs signal changes in the intracranial arteries (ICAs) were suggested to reflect vessel volume fluctuations related to the vascular contractility5, 6. In this study, we aimed to explore these subclinical changes in vascular health using fMRI, and to understand their associations with brain degeneration and cognitive functions.Methods

A total of 212 subjects were enrolled from a prospectively collected community cohort. All subjects signed informed consent on admission and underwent a complete assessment of cognitive functions and multi-modality magnetic resonance imaging scans (3D T1W images, T2W images and T2 FLAIR images, rsfMRI images, 3D arterial spin labeling (ASL) images).In this study, several markers (cerebral blood flow, cerebral blood transit time, and vascular contractility in ICAs) was used to reflect subclinical vascular function changes, and lacunes and WMH to reflect parenchymal damages. Lacune was assessed according to the Standards for Reporting Vascular Changes on Neuroimaging (STRIVE)9. The volume of WMH was quantified using a deep-learning based segmentation method and then normalized by intracranial volume (ICV). Cerebral blood flow in gray matter (GM CBF) was calculated from ASL image by ExploreASL toolbox.

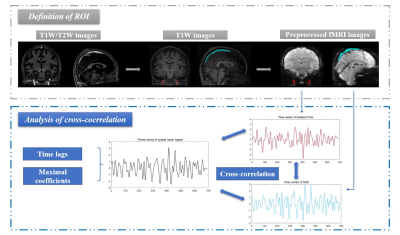

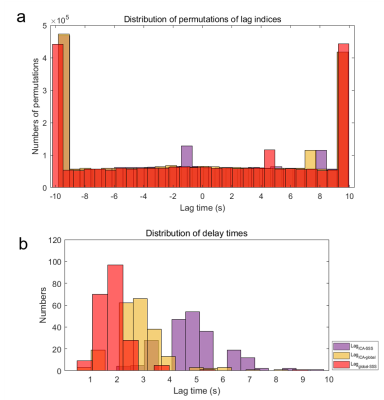

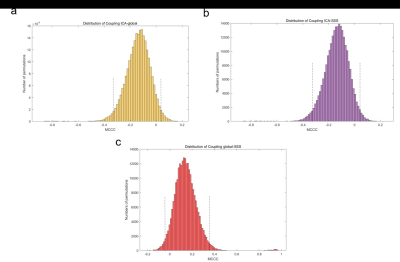

To obtain transit time from large arteries to the venous side, bilateral ICAs and the sagittal sinus (SSS) and were defined as our regions of interest (ROI). Consistent with previous studies5, 6, these ROIs were identified using T1- and T2 -weighted image, and then registered to the fMRI image which had processed by band-pass filtering at 0.01-0.1HZ. We set the ICAs signal as reference and calculated the maximal cross-correlation (MCCC) and lag time between the ICAs, SSS and global mean signal over a range time lags (-10s ~ 10s) for individuals. Above processed procedures were shown in the Figure 1. We verified the credibility of the above cross-correlation between two signals by permutation tests and excluded spurious correlation. In the following-up statistical analysis, we used the absolute values of the coupling indices for easily understanding. The result of permutation tests and the real correlation between signals were shown in Figure2 and 3. A larger value represents a better coupling between the two signals. To assess vascular contractility, standard deviation of the signal series of the ICA (ICAstd_wave) was quantified. A larger ICAstd_wave suggested a larger fluctuation of vessel diameters.

We used the correlation analysis to explore the relationship between the confounders (age, sex, ICV) and subclinical vascular biomarkers (lag indices, ICAstd_wave and GM CBF). The multiple linear regression models were performed to explore the relationship between the subclinical biomarkers and vascular risks and SVD biomarkers when controlled for above confounds. Finally, we investigated the correlation between all cerebrovascular healthy indictors and cognition assessments (MMSE and MOCA) using multiple linear regression when adjusted for age, sex and education. In all regression models, we used the variance inflation factor (VIF) to monitor multicollinearity.

Results

We found that the contractility of the ICAs was negatively associated with age (β = -0.150, p = 0.029). Subjects with diabetes have significantly longer blood transit time from the ICAs to capillary (β = 0.155, p = 0.024), controlling for age, sex and the intracranial volume. Furthermore, subjects with larger contractility in ICAs had a lower risk of lacunes (OR = 0.404, p = 0.02). Higher CBF in total gray matter (β = 0.163, p = 0.009) and larger contractility (β = 0.126, p = 0.045) in ICAs were associated with better cognition.Conclusion

The present study investigated subclinical vascular changes in a relatively young community cohort and found that: (1) decreased vascular contractility was associated with aging; (2) longer blood transit time was related to the presence of diabetes; (3) subjects with lower vascular contractility had more lacunes, controlling for vascular risk factors; (4) lower vascular contractility and GM CBF were associated with worse cognition. Our study demonstrated the importance of subclinical vascular health to further parenchymal damage and cognitive function, highlighting the need for early monitoring. In the current study, sLFOs signal we obtained is mixed with other confounding factors - the effects of respiratory and cardiac beats which can’t be removed by simple filter. Further studies are needed to discuss the correlation between this indicator and vascular health to enhance its credibility. Additionally, due to the cross-sectional nature of the present study, whether these subclinical markers could predict further vascular related brain damages and cognitive decline still need to be understood in longitudinal studies.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. van Veluw SJ, Arfanakis K, Schneider JA. Neuropathology of Vascular Brain Health: Insights From Ex Vivo Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Histopathology Studies in Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. Stroke 2022; 53(2): 404-415.

2. Cannistraro RJ, Badi M, Eidelman BH, Dickson DW, Middlebrooks EH, Meschia JF. CNS small vessel disease: A clinical review. Neurology 2019; 92(24): 1146-1156.

3. Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M. Small vessel disease: mechanisms and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol 2019; 18(7): 684-696.

4. Tong Y, Hocke LM, Frederick BB. Low Frequency Systemic Hemodynamic "Noise" in Resting State BOLD fMRI: Characteristics, Causes, Implications, Mitigation Strategies, and Applications. Front Neurosci 2019; 13: 787.

5. Tong Y, Yao JF, Chen JJ, Frederick BD. The resting-state fMRI arterial signal predicts differential blood transit time through the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2019; 39(6): 1148-1160.

6. Yao JF, Wang JH, Yang HS, Liang Z, Cohen-Gadol AA, Rayz VL et al. Cerebral circulation time derived from fMRI signals in large blood vessels. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019; 50(5): 1504-1513. 7. Amemiya S, Kunimatsu A, Saito N, Ohtomo K. Cerebral hemodynamic impairment: assessment with resting-state functional MR imaging. Radiology 2014; 270(2): 548-55.

8. Yan S, Qi Z, An Y, Zhang M, Qian T, Lu J. Detecting perfusion deficit in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment patients by resting-state fMRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019; 49(4): 1099-1104. 9. Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, Cordonnier C, Fazekas F, Frayne R et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12(8): 822-38.

Figures

Figure 1. The flow chart of the processing and analytical procedure.

Bilateral internal carotid arteries (ICAs, red masks) and superior sagittal sinus (SSS, light blue mask) were identified from the high resolution T1w/T2w images and T1W images and then projected to low-resolution fMRI image. Averaged time series of ICAs and SSS were extracted from fMRI images, and the cross-correlation was applied to calculate maximal coefficients and time lags between each time series and the global mean signal.

Figure 2. Contrast of distribution of delay times in permutation tests and actual state.

(a). The delay time between the random matching two signals (LagICA-SSS, purple column; LagICA-global, yellow column; Lagglobal-SSS, red column) were concentrated on the boundaries (-10 s, 10 s) and the rest lags uniformly distributed in -10 - 10 s. (b). The actual distribution of delay times was regular and concentrated on corresponding range (2.1-3.5 s for LagICA-global; 1.4 - 2.1 s for Lagglobal-SSS and 4.2 - 5.6 s for LagICA-SSS).

Figure3: The distribution of permutation tests of MCCC for three sLFO BOLD signals, which included (a). CouplingICA-global (between the ICAs and global mean signal), (b). CouplingICA-SSS (between ICAs and SSS) and (c). Couplingglobal-SSS (between global mean signal and SSS).

X-axes, MCCC, y-axes, the numbers of permutation tests. Dotted lines in each picture represent the upper and lower confidence intervals. MCCC, maximal cross-correlation.