2059

Development of an external butterfly coil for sodium (23Na) MRI of human prostate cancer1Medical Biophysics, Western University, London, ON, Canada, 2Lawson Imaging, Lawson Health Research Institute, London, ON, Canada, 3Robarts Research Institute, London, ON, Canada, 4Medical Imaging, Western University, London, ON, Canada, 5Medical Imaging, St. Joseph's Health Care, London, ON, Canada, 6Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, Toronto, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Prostate, Cancer

This abstract focuses on the development of an external, non-invasive butterfly coil for sodium MRI of human prostate cancer. Sodium MRI of healthy male volunteers and patients revealed higher sodium signal and ADC in the peripheral zone compared to the transition zone of the prostate, and a lower sodium signal and ADC in tumour lesions relative to healthy tissue. Further work will aim to characterize the sensitivity of this coil to detect tumours, which may enhance the workflow of sodium MRI in prostate cancer studies compared to conventional endorectal coils.Introduction

Sodium (23Na) MRI is a molecular imaging technique that can detect the increased tissue sodium concentration (TSC) exhibited in several tumour types. For prostate cancer (PCa) imaging, sodium MRI is conventionally performed using an endorectal coil to facilitate a higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) [1]–[4]. Such studies have quantified TSC in normal prostate tissue and prostate tumours [2], [3] and have demonstrated a significant correlation between TSC and histological Gleason grade [1]. However, endorectal coils are associated with a limited field of view, increased scan times, gland deformation, and patient discomfort, which constrain the clinical utility of sodium MRI for PCa imaging. To address these challenges, this work focuses on the development of a completely external, non-invasive butterfly coil for sodium MRI of PCa.Methods

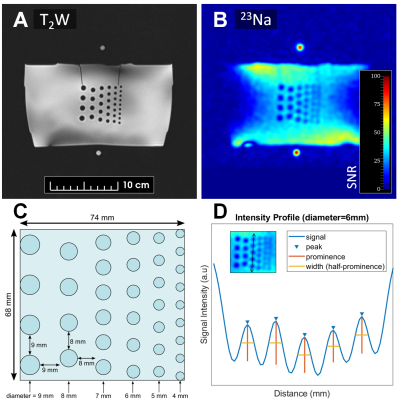

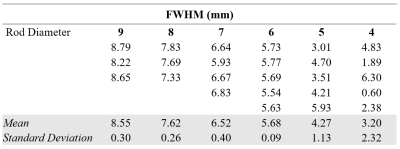

All MR imaging was performed using a 3 Tesla PET/MRI scanner (Siemens Biograph mMR). The radiofrequency system consisted of an external, PET-compatible, flexible transmit/receive butterfly coil (diameter=18cm, tuning=32.6 MHz) built in-house for sodium imaging and a commercial flexible anterior and rigid spine array for proton imaging. Sodium imaging was performed using a 3D density-adapted radial projection sequence (TR=50ms; TE=0.8ms; nominal resolution=5×5×5mm3; FOV=36×36×10cm3; number of projections=11310; samples per projection=2500; acquisition window=25ms, repetitions=3; total scan time=28min) [5]. Sodium images were reconstructed offline using the Michigan Image Reconstruction Toolbox (MIRT) [6] in MATLAB. High-resolution T2W images (TR=1700ms; TE=101ms; FOV=360×360mm2; resolution=1.13×1.13mm3) were acquired as an anatomical reference. For human scans, DWI was also performed to generate ADC maps (TR=5200ms; TE=96ms; resolution=1.25×1.25mm2; b values=0,100,800s/mm2). Co-registration of the reconstructed sodium images to the proton images was achieved with a thin plate transformation using the Landmark Registration module on 3D Slicer.To test the achievable resolution of the butterfly coil, sodium images were acquired in a 74×68×50mm3 acrylic phantom. The phantom consisted of equally spaced, solid cylindrical rods (diameters=4-9mm) submerged in a container of 50 mM NaCl. Full width at half maximum (FWHM) was measured across the rods using the Signal Processing Toolbox in MATLAB.

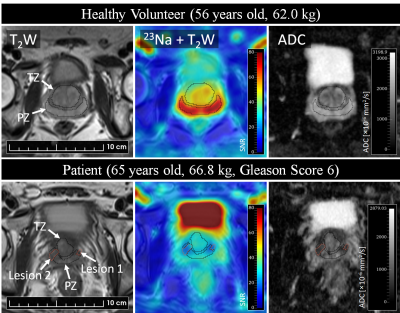

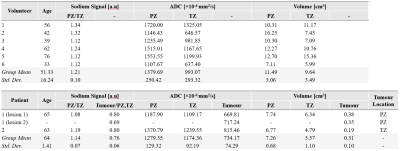

Sodium MRI was then performed on 6 healthy volunteers (age = 51.33±16.24 years, weight = 75.33±16.03 kg) and two patients with biopsy-proven PCa (age = 64.0±1.41 years, weight = 72.40±7.92 kg). Following sodium MRI, the butterfly coil was removed, and the anterior and spine array was attached for proton T2W and DWI MRI. All MR images were acquired in an oblique axial plane perpendicular to the prostatic urethra. A radiologist with 6 years of experience in pelvic imaging (V.K.) used the proton MRI datasets to 1) delineate the peripheral zone (PZ) and transition zone (TZ) in each volunteer and patient, 2) delineate the tumour in patients, and 3) evaluate tumours based on the prostate imaging reporting and data system (PIRADS) [7]. PZ and TZ tumours were identified based on ADC maps and T2W images, respectively. Signal offset was removed from the sodium images by voxel-wise subtraction of the mean background signal. The relative sodium signal intensity was then measured for PZ/TZ tissue in volunteers and patients, and in the tumour relative to normal PZ or TZ in which it was located.

Results and Discussion

The resolution phantom is shown in Figure 1, with corresponding FWHM measurements between the rods reported in Table 1. Based on these phantom measurements, prostatic lesions of at least 6 mm in diameter can be resolved using this butterfly coil. For reference, mean lesion size in PCa as detected by multiparametric MRI has been reported to be 15.7 mm [8].Representative volunteer and patient images are shown in Figure 2, where sodium signal can be detected throughout the whole prostate and pelvic region with high mean SNR (PZ SNR=37.6; TZ SNR=32.3). Table 2 lists relative sodium signal intensities and ADC values. For all subjects, sodium signal in PZ was greater than that in TZ, consistent with previous reports [2], [3]. This finding may be attributed to structural differences in these zones that influence intra- and extracellular volume fraction which, in turn, affect total TSC, such as looser stroma in PZ [9], [10]. Similarly, ADC was higher in PZ compared to TZ, and low in tumour lesions [11]. In contrast to prior sodium MRI studies, PZ and TZ tumour lesions had a lower signal intensity relative to normal PZ and TZ. However, it must be noted that there is intratumour and intertumour heterogeneity in TSC, with some prostatic tumours exhibiting higher TSC compared to normal PZ and TZ [2], [3]. Furthermore, both patients in this study presented with PIRADS 3 based on proton MRI, for which findings on sodium MRI may be similarly equivocal. Given the limited patient sample size in the current study, further investigation is warranted to determine whether the butterfly coil is sensitive to these differences in tumour TSC.

Conclusion

Based on initial results in healthy volunteers and patients, the butterfly coil achieved high SNR throughout the entire prostate gland. Higher sodium levels and ADC were detected in PZ relative to TZ, in agreement with literature. Further work will aim to characterize in vivo imaging sensitivity of this coil to tumours, which may enhance the workflow of sodium MRI in PCa studies compared to conventional endorectal coils.Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the U.S. Department of Defense (PC180055) and the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (IA-028).References

[1] N. C. Broeke et al., “Characterization of clinical human prostate cancer lesions using 3.0-T sodium MRI registered to Gleason-graded whole-mount histopathology,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, vol. 49, no. 5, pp. 1409–1419, 2019.

[2] T. Barrett et al., “Quantification of Total and Intracellular Sodium Concentration in Primary Prostate Cancer and Adjacent Normal Prostate Tissue with Magnetic Resonance Imaging,” Invest. Radiol., vol. 53, no. 8, pp. 450–456, Aug. 2018.

[3] T. Barrett et al., “Molecular imaging of the prostate: Comparing total sodium concentration quantification in prostate cancer and normal tissue using dedicated 13C and 23Na endorectal coils,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 90–97, 2020.

[4] A. Farag et al., “Unshielded asymmetric transmit-only and endorectal receive-only radiofrequency coil for 23Na MRI of the prostate at 3 tesla,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 436–445, 2015.

[5] A. M. Nagel, F. B. Laun, M. A. Weber, C. Matthies, W. Semmler, and L. R. Schad, “Sodium MRI using a density-adapted 3D radial acquisition technique,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 62, no. 6, pp. 1565–1573, 2009.

[6] Fessler JA, "Michigan Image Reconstruction Toolbox," available at https://web.eecs.umich.edu/~fessler/code/, downloaded Sep 2021.

[7] “Prostate Imaging-Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) v2,” Am. Coll. Radiol., 2015.

[8] A. Pooli et al., “Predicting Pathological Tumor Size in Prostate Cancer Based on Multiparametric Prostate Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Preoperative Findings,” J. Urol., vol. 205, no. 2, pp. 444–451, Feb. 2021.

[9] A. Bhavsar and S. Verma, “Anatomic Imaging of the Prostate,” BioMed Research International, vol. 2014. Hindawi Limited, 2014.

[10] L. O. Poku, M. Phil, Y. Cheng, K. Wang, and X. Sun, “23Na-MRI as a Noninvasive Biomarker for Cancer Diagnosis and Prognosis,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 995–1014, 2021.

[11] R. Manetta et al., “Correlation between ADC values and Gleason score in evaluation of prostate cancer: Multicentre experience and review of the literature,” Gland Surgery, vol. 8. pp. S216–S222, 2019.

Figures