2024

Initial observations and potential pitfalls when validating respiratory correlated MRI for radiotherapy planning.

Evanthia Kousi1, Joan Chick1, Andreas Wetscherek1, Julie Hughes2, Georgina Hopkinson2, Jessica Gough2,3, Rosalyne Westley2,3, Radhouene Neji4, Simeon Nill1, Dow-Mu Koh2,3, and Uwe Oelfke1

1Joint Department of Physics, The Institute of Cancer Research and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom, 2The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom, 3The Institute of Cancer Research, London, United Kingdom, 4MR Research Collaborations, Siemens Healthcare, Frimley, United Kingdom

1Joint Department of Physics, The Institute of Cancer Research and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom, 2The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom, 3The Institute of Cancer Research, London, United Kingdom, 4MR Research Collaborations, Siemens Healthcare, Frimley, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Radiotherapy, 4D-MRI, Respiratory correlated MRI, radiotherapy planning

In this abstract we present our initial results from the validation of a respiratory correlated 4D MRI golden angle stack of stars radial sequence prior to its clinical implementation and highlight potential experimental pitfalls to avoid that may impact motion range estimations.

Correct phantom set up reduced motion underestimations by 3%-18% for the simulated respiratory waveforms considered. Larger motion discrepancies observed for the low amplitude motion which improved by increasing the number of bins.

Introduction

MRI utilised for abdominal radiotherapy planning is challenging due to the significant respiratory motion.Various methods to address respiratory motion are used clinically for motion compensation in radiotherapy, including breath-holding, respiratory gating and active breathing control [1]. These methods could account for respiratory motion and reduce the margins applied at treatment but may be infeasible for seriously ill patients.

4D-MRI broadly refers to the respiratory correlated 3D free-breathing acquisition for motion characterisation. Extensive previous research highlighted a number of potential applications of 4D-MRI in radiotherapy planning [2].

In this study, we present our initial experience obtained during the validation of a 4D-MRI clinical golden angle stack-of-stars radial sequence with a 4D motion phantom before its clinical utilisation, highlighting observations and experimental setup errors which may compromise motion range estimations.

Methods

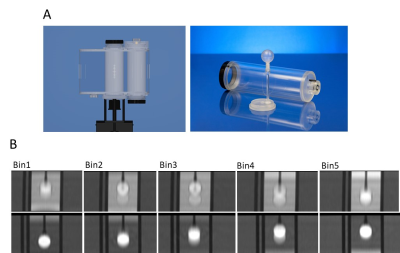

All scans were performed at 1.5T (MAGNETOM Sola, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using a 4D respiratory motion phantom (Figure 1A). The phantom was programmed to simulate respiration in the craniocaudal direction.Several sinusoidal waveforms with different amplitudes were investigated (Table 1). The different experimental setups of the 4D phantom included: phantom’s cylindrical insert empty, filled with a CuSO4 solution, and filled with distilled water.

The 4D-MRI vendor sequence consists of a self-gated 3D T1-w gradient echo acquisition with a golden angle stack-of-stars radial k-space trajectory [3]. The self-gating signal is used for the amplitude-based retrospective sorting of the acquired data in respiratory phase bins prior to image reconstruction.

Our initial experimental data were acquired axially with the 4D-MRI sequence provided by the vendor (TR/TE=4.1ms/2.39ms,Voxel size=1.98x1.98x6mm3(3mm reconstruction),FOV=380mm, bandwidth=898Hz/px,base resolution=192px) and retrospectively reconstructed into 5 and 10 bins. The number of radial views was set according to the following equation to minimise scanning time while maintaining adequate data sampling:

$$radial\ views = 2(or\ pi/2 =1.57)*(base\ resolution)*(number\ of\ defined\ bins)$$

For motion analysis, coronal reformats were obtained for each individual bin and the average volumes (ImageJ, version 1.53t). The moving sphere was then automatically outlined following image thresholding and the centre-of-mass (COM) coordinates were analysed (MATLAB, R2021a).

Peak-to-peak (pk-to-pk) displacements were determined from the craniocaudal co-ordinates of the COM. The values were compared against the theoretical pk-to-pk values (Table 1), investigating the effect of phantom liquid setup, number of bins, and motion amplitude.

Results

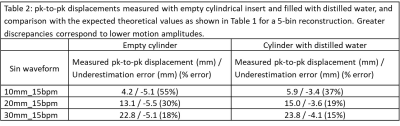

When the phantom's cylindrical insert was empty, the 5 bins data reconstruction demonstrated considerable motion underestimations (18-55%) of approximately 5mm for all employed sinusoidal waveforms (Table 2). Small improvements were observed in the sphere’s displacement estimations when the cylindrical insert was filled with distilled water (Table 2).When the cylindrical insert was filled with a CuSO4 solution (T1CuSO4 = 800ms, T1sphere = 340ms) the sphere’s outline was compromised due to ghosting believed to be due to the solution’s high signal intensity. This was particularly seen for the inner bins with increased residual motion (Figure 1B). Therefore, these images were not included further for COM analysis.

Figure 2A illustrates the motion ghosting on the average MR images, which elongates as the amplitude of motion increases. Figure 2B shows increased radial streaking artefact seen with the 10 bins reconstruction.

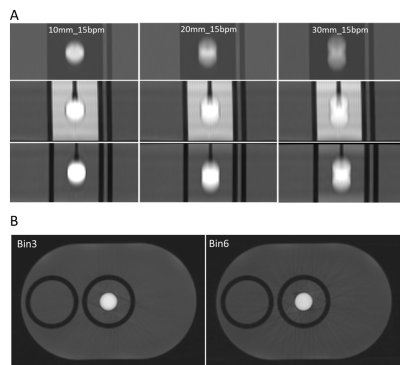

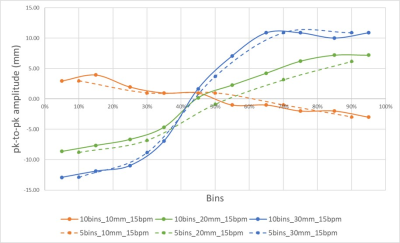

The COM motion pattern when data were sorted into 5 and 10 bins, is similar as illustrated in Figure 3, however, results show that expiration and inspiration are not always assigned to the same bin.

The 10-bin reconstruction improved pk-to-pk amplitude measurement by 17% compared to the 5-bin reconstruction, however, for the higher amplitude waveforms the increase was less than 6%.

Discussion

The self-gating-based surrogate signal relies on the change in signal due to the object’s motion.Motion underestimations were larger when the cylindrical insert was empty. Motion characterisation improved when the cylinder was filled with distilled water due to the sufficient signal modulation of the liquid in the cylinder during the sphere’s motion. The contrast between the solution in the sphere and the surrounding liquid is another factor that may compromise motion estimations by altering the appearance of motion ghosts.

The 5-bin and 10-bin 4D-MRI demonstrated very similar motion traces, but the motion pattern differed for the low-amplitude waveform because the binning does not distinguish between inspiration and expiration as 4D-CT does.

The larger pk-to-pk displacement discrepancy was observed for the low-amplitude motion, suggesting that the surrogate signal may not represent the input motion accurately. In a clinical study, Perkins et al found low correlation between the surrogate signal and shallow respiratory motion (6mm median amplitude 6mm) [4]. Another possible explanation for the observed discrepancy is the suppression of the sphere’s motion by regularisation during image reconstruction [5]. Increasing the number of bins lead to a small improvement in motion detection.

Conclusion

Incorrect phantom setup may lead to avoidable underestimation of motion. In addition, increasing the number of bins does not necessarily lead to considerably improved motion characterisation. Through-plane and in-plane image quality deterioration due to the low slice resolution in the motion direction and the increase of streaking artifacts with increased number of bins could negatively affect the correctness of motion estimations.Further work is needed to investigate the potential reasons for the observed motion underestimations associated with the scanning plane, surrogate signal robustness, and motion direction prior to utilising 4D-MRI clinically.

Acknowledgements

This study represents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre and the Clinical Research Facility in Imaging at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and The Institute of Cancer Research, London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. This work was supported by the Institute of Cancer Research and Cancer Research UK (CRUK) grant number C33589/A28284References

1. Schmidt M. et al. Phys Med Biol. 2015 Nov 21; 60(22): R323–R361.2. Stemkens B. et al, Phys Med Biol, 2018 63(21):21

3. Winkelmann S, et al. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2007;26:68–76.

4. Perkins T, et al Physics and Imaging in Radiation Oncology 2021;17:32-35

5. Freedman J N, et al, Invest Radiol. 2017 Oct;52(10):563-573

Figures

Figure1: A) Modus QUASAR phantom showing the body phantom (left)

and movable cylindrical insert with offset 3.2cm diameter sphere (right). B) 5-bins

reconstructions for sinusoidal waveform 30mm_15bpm using CuSO4 solution (top

row) and distilled water (bottom row) showing residual motion ghosting in each

bin.

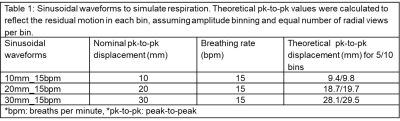

Table 1: Sinusoidal waveforms to simulate

respiration. Theoretical pk-to-pk values were calculated to reflect the

residual motion in each bin, assuming amplitude binning and equal number of

radial views per bin.

Table 2: pk-to-pk displacements measured with empty cylindrical insert

and filled with distilled water, and comparison with the expected theoretical

values as shown in Table 1 for a 5-bin reconstruction. Greater discrepancies

correspond to lower motion amplitudes.

Figure

2: A) Coronal average reformats with the cylindrical insert empty (top row), filled with CuSO4 solution (middle

row), distilled water (bottom row). B) Inner bin axial images from 5-bin (left) and 10-bin (right) reconstructions. Radial streak artifact is apparent. All images were acquired with 3014 radial views.

Figure 3: COM motion trace for 5 bins and 10 bins

reconstructions

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/2024