2015

Consolidation of expert ratings of motion artifacts using hierarchical label fusion1Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 2Department of Radiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 3Northeastern University, Boston, MA, United States, 4Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 5Department of Radiology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA, United States, 6Data Science Office, Mass General Brigham, Somerville, MA, United States, 7Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, Massachusetts Institute of Technology,, Cambridge, MA, United States, 8Harvard-MIT Divison of Health Sciences and Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Motion Correction

Intra-scan motion costs tens of thousands of dollars per scanner annually due to the need to repeat non-diagnostic scans1. When assessing the scale of the problem and potential solutions, radiologists’ ratings of artifacts are considered the gold standard. However, inconsistent and conflicting ratings must be consolidated into a single gold-standard. We introduce a hierarchical label fusion algorithm that infers each rater's performance and promotes consistency across slices from a volume. This algorithm reduces label noise compared to majority votes, and allows non-expert ratings to be calibrated and included as additional silver-standards.Introduction

Intra-scan subject motion is the primary cause of artifacts in MRI, leading to the acquisition of data that cannot be used for diagnosis2 or population analysis3. Several approaches are being developed for motion artifact detection and correction, including machine learning approaches that need to be trained or validated with ground truth ratings of motion artifacts. Since this rating process is inherently subjective, there can be disagreement between raters. Moreover, radiologists time is valuable, and augmenting datasets with labels from non-expert raters is a potential approach for reaching the critical mass of labeled images necessary to train robust algorithms. In this abstract, we propose to consolidate ratings from experts and non-experts using a hierarchical extension of STAPLE4 that accounts for correlations of artifact scores across slices from the same volume.Theory

The STAPLE algorithm4 relies on a forward statistical model of each rater’s confusion, i.e., the statistical frequency at which a rater $$$j$$$ assigns a label $$$k$$$ to an image $$$n$$$ when the true label is $$$\hat{k}$$$. This is summarized as $$$p(x_{nj} = k | y_j = \hat{k}) = \theta_{jk\hat{k}}$$$. The model also defines global class frequencies $$$p(y_n=k)=\pi_k$$$. Its regularized variant (MAP-STAPLE5) introduces a prior over each confusion matrix $$$\boldsymbol{\Theta}_j$$$ in the form of a Dirichlet distribution, which usually assumes that raters are often right. We extend this model by introducing an additional level for the true rating of a volume, and a confusion matrix from the volume to the slice level. The aim of this model is to use the correlation of artifact scores within a volume to reduce noise in ratings but also allow some flexibility such that one may find a slice with no artifact in a mostly corrupted volume. This yields the likelihoods:- $$$p(x_{nsj}=k | y_{ns}=\hat{k}) = \theta_{jk\hat{k}}$$$ (rater's performance)

- $$$p(y_{ns}=\hat{k} | z_n=\bar{k}) = \psi_{\hat{k}\bar{k}}$$$ (intra-volume variance)

- $$$p(z_n=k) = \pi_k$$$ (class frequency)

- $$$p(\boldsymbol{\theta}_{j\hat{k}}) = \operatorname{Dir}(\boldsymbol{\alpha})$$$

- $$$p(\boldsymbol{\psi}_{\bar{k}}) = \operatorname{Dir}(\boldsymbol{\beta})$$$

- $$$p(\boldsymbol{\pi}) = \operatorname{Dir}(\boldsymbol{\gamma})$$$

Variational updates

- $$$q(y_{ns}=\hat{k}) \propto \exp( \sum_{\bar{k}} \mathbb{E}[z_n=\bar{k}] \mathbb{E}[\ln\psi_{\hat{k}\bar{k}}] + \sum_{jk} [x_{nsj}=k] \mathbb{E}[\ln\theta_{jk\hat{k}}] )$$$

- $$$q(z_n=\bar{k}) \propto \exp( \mathbb{E}[\ln\pi_{\bar{k}}] +\sum_{s\hat{k}} \mathbb{E}[y_{ns}=\hat{k}]~\mathbb{E}[\ln\psi_{\hat{k}\bar{k}}] )$$$

- $$$q(\boldsymbol{\theta}_{j\hat{k}}) = \operatorname{Dir}(\boldsymbol\alpha +\sum_{ns}\mathbb{E}[y_{ns}=\hat{k}] \mathbf{x}_{nsj})$$$

- $$$q(\boldsymbol{\psi}_{\bar{k}}) = \operatorname{Dir}(\boldsymbol{\beta}+\sum_{ns}\mathbb{E}[z_n=\bar{k}]\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{y}_{ns}])$$$

- $$$q(\boldsymbol\pi) = \operatorname{Dir}(\boldsymbol\gamma+\sum_{n}\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{z}_n])$$$

Methods

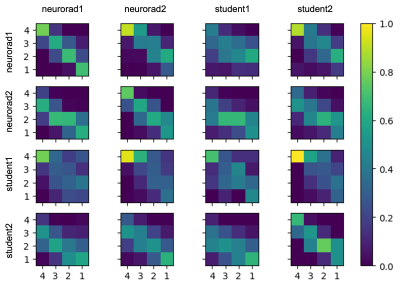

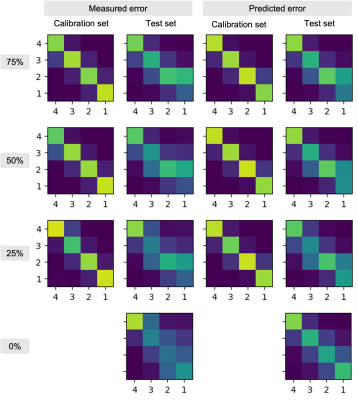

Two experienced neuroradiologists and two undergraduate students were tasked with rating the level of motion artifacts within brain parenchyma in slices from 2D T1-FLAIR and T2-FLAIR volumes, in four classes: “no motion” (1); “mild motion” (2); “moderate motion” (3); “severe motion” (4). The students received training in classification of motion artifacts and an annotation protocol with examples of confounding artifacts such as non-brain (neck/eyes), pulsation, implants, RF spikes, or zipper artifacts.A total of 1052 slices from 51 T1-weighted volumes and 807 slices from 83 T2-FLAIR volumes were evaluated by these four raters. Each slice was rated individually, i.e., all slices from the same volume were not presented to the rater at once. Ten percent of the images were presented twice to each rater to evaluate within-rater variability (Figure 1). We fitted two variants of our algorithm: one where raters share the same prior, and one where radiologists are expected to perform better than non-radiologists. Finally, in order to show that this model can be used to calibrate non-expert raters and predict silver-standard scores, we fitted the model to a subset of the data that includes all student ratings but only some expert ratings (25, 50, or 75 %). Our implementation is available at https://github.com/balbasty/variational_staple

Results

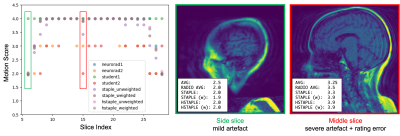

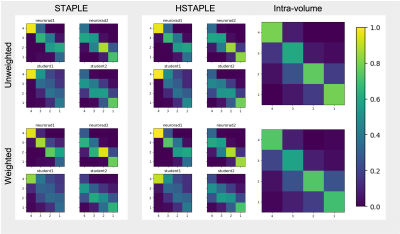

We show in Figure 2 that our model allows mistakes to be corrected thanks to differential expert weighting and within-volume smoothing while preserving scores where both experts agree. While one may argue that all raters are wrong about this specific lateral slice (there was motion during acquisition), we emphasize that we target the level of artifact. Lateral slices do appear to be less corrupted and should keep their low motion rating. Figure 3 shows the performance matrices estimated by all models, as well as intra-volume variability matrices estimated by the two hierarchical models. We demonstrate in Figure 4 that valid silver standards can be obtained from well-calibrated non-expert ratings. By "valid", we mean that the model's confidence in the consolidated student labels matches the effective error with respect to the consolidated expert ratings.Conclusion

We presented a label fusion method developed for the difficult task of motion artifact categorization, which is subjective (between-rater disagreement) and often ambiguous between adjacent artifact categories (within-rater variability). The original STAPLE method can resolve differences of opinion between raters to produce consolidated labels for training or validation of artifact prediction algorithms. The hierarchical STAPLE algorithm exploits the presence of correlations between subsets of labels - i.e. between slices from the same volume - to reduce label noise. We have shown that these labels are less noisy than the original ratings and can capture genuine variation in artifacts within a volume. We further showed that valid silver-standard ratings can be produced by calibrated non-expert raters.Acknowledgements

We thank Dan Rettmann, Sabrina Qi, Eugene Milshteyn, Suchandrima Banerjee, and Anja Brau for helpful discussions and assistance. We are grateful for funding from General Electric Healthcare.

Additional support for this research was provided in part by the BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network (U01 MH117023) the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (P41 EB015896, R01 EB023281, R21 EB018907, R01 EB019956, P41 EB030006, R21 EB029641), the National Institute of Mental Health (RF1 MH121885, RF1 MH123195), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01 NS070963, R01 NS083534, R01 NS105820). Additional support was provided by the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research (U01 MH093765), part of the multi-institutional Human Connectome Project.

The project was made possible by the resources provided by Shared Instrumentation Grants (S10 RR023401, S10 RR019307, S10 RR023043) and by computational hardware generously provided by the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center (https://www.masslifesciences.com).

Bruce Fischl has a financial interest in CorticoMetrics, a company whose medical pursuits focus on brain imaging and measurement technologies. This interest is reviewed and managed by Massachusetts General Hospital and Mass General Brigham in accordance with their conflict of interest policies.

References

- Slipsager et al, JMRI (2020) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32144848/

- Andre et al, J Am Coll Radiol (2015) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25963225/

- Reuter et al, NeuroImage (2015) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25498430/

- Warfield et al, TMI (2004) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15250643/

- Commowick & Warfield, MICCAI (2010) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20879379/

- Bishop (2006) https://link.springer.com/book/9780387310732

Figures