1998

A combined model-based and ML-based approach performs better than model-based or ML-based applied individually

Srikant Kamesh Iyer1, Hassan Haji-Valizadeh1, and Samir Sharma1

1Canon Medical Research USA, Inc., Mayfield, OH, United States

1Canon Medical Research USA, Inc., Mayfield, OH, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, Motion Correction

A motion correction framework was developed to suppress artifacts from rigid and non-rigid motion using a combination of model-based and ML-based approaches. The performance of this framework was compared with model-based only and ML-based only motion correction approaches on motion-simulated data and motion-corrupted in-vivo data using visual inspection and image quality metrics. The combined approach showed superior image quality than model-based and ML-based approaches applied individually.Introduction:

MRI is susceptible to image quality (IQ) degradation due to motion. Several model-based motion correction (MoCo) approaches [1-3] have been developed for retrospective MoCo. These model-based approaches can correct rigid and non-rigid motion. Moreover, model-based approaches use an iterative reconstruction pipeline to enforce data fidelity, which enables preservation of the acquired data and SNR. Despite their advantages, model-based methods suffer from long reconstruction times. More recently, multiple ML-based approaches [4-10] have been developed for rapid MoCo. In ML, the computationally complex motion modelling occurs during training. ML is limited by reduced performance for motion not included in training and blurring of features for cases with high motion. We demonstrate a new approach for MoCo by combining model-based and ML-based approaches. We evaluate the proposed technique with several C-spine (axial, sagittal T2w and sagittal STIR), and brain (axial, sagittal T2w and axial FLAIR) applications using visual inspection and IQ metrics. We show that the proposed combination has greater robustness to motion than model-based or ML-based approaches applied individually.Methods:

The proposed approach combines a model-based and ML-based MoCo to remove artifacts due to sporadic motion. The model-based method corrects for rigid and non-rigid motion using navigator data. The ML-based method uses a complex-valued residual U-Net. Both R=1 and R=2 datasets were used for ML training. A total of 12,000 with/without motion pairs, generated by adding various amount of rigid motion to motion free data [8], were used for supervised ML training. Mini-batch=18, ADAM optimizer, learning rate=0.001, and 20% drop-out were used for ML training.Data acquisition: All datasets were acquired under IRB approval and informed consent on a Orian 1.5T and Galan 3T (Canon Medical Systems Corporation, Tochigi, Japan).

Motion Simulation: A total of 12 no motion datasets were acquired for the simulations. Both R=1 and R=2 acceleration was used for the motion simulation. Two different types of sporadic motion were simulated using the fully sampled motion free images. Motion type 1: A combination of in-plane rigid motion (translation= ±15mm and rotation= ±20 degrees) and out of plane (OOP) motion was simulated. OOP motion was simulated by using k-space from the neighboring slice position (±1 slice position). Motion shots and the amount of rigid motion were randomly chosen. A motion frequency of one motion event per minute was used for simulations. Motion was added to both imaging data and navigator signal. Motion type 2: A two rest-state scenario was simulated. Type 2 motion was simulated by randomly choosing a transition motion shot. Shots prior to the transition shot were assumed to be in a different fixed motion state than shots after the transition shot. The transition motion shot was randomly assigned as either OOP or large rigid translation motion.

A total of 5 random motion simulation trials were run on each of the 12 motion free datasets. Simulations were performed separately for R=1 and R=2. The total number of simulations was 120 (=5x12x2). The motion simulated datasets were processed using (a) model-based method only, (b) ML-based method only and (c) combined model-based and ML method. Structural similarity index metric (SSIM) and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) were calculated for each method using the no motion data as reference and Wilcoxon’s signed-rank was used to test for statistical significance.

Motion corrupted in-vivo data: An axial T2w brain image was acquired on a 3T scanner and the volunteer was instructed to rotate their head once. A sagittal T2w C-spine image was acquired at 1.5T on another volunteer and was instructed to twitch once every minute.

Results:

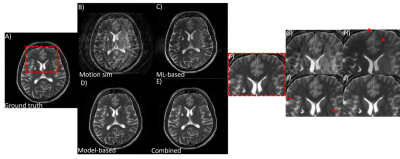

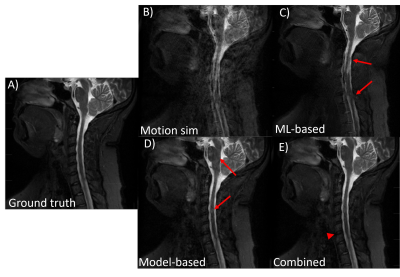

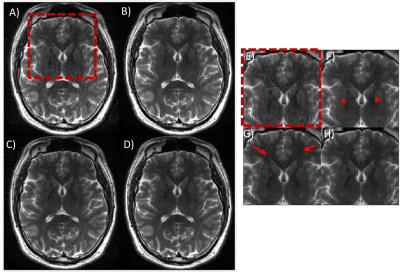

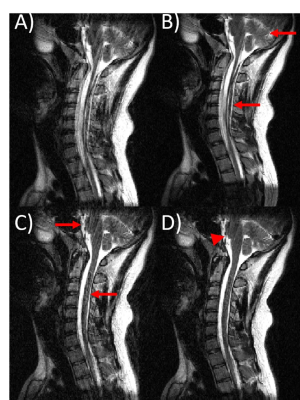

Fig1 shows the results for an axial T2w brain with type 1 simulated motion, and Fig2 shows results of a sagittal T2w C-spine with type 2 simulated motion. In both Fig1 and Fig2, combined model-based and ML-based yields superior IQ compared to ML-based and model-based approaches applied individually. The mean SSIM and PSNR for the different approaches are compared in Fig3. For both type 1 (Fig3A) and type 2 (Fig3B) motion, the combined approach achieved the highest SSIM and PSNR. Proposed method performance on in-vivo axial T2w brain and sagittal T2 C-spine are shown in Fig4 and Fig5 respectively. The combined model-based and ML-based method achieves the best IQ for in-vivo imaging.Discussion:

Combined model-based and ML-based MoCo consistently showed better IQ than ML-based or model-based MoCo applied individually. The model-based approach often showed significant residual motion artifacts, and the ML-based approach caused blurring of sharp features. This led to lower SSIM and PSNR scores than the combined approach for simulation analysis. Combined model-based and ML-based MoCo prevented feature blurring seen with ML and suppressed residual motion artifacts seen with model-based MoCo. Similar results were also seen in the in-vivo examples.Conclusion:

The results show that combining model-based and ML-based approaches yields superior artifact suppression than model-based or ML-based approaches applied individually.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Batchelor PG, et al. Matrix description of general motion correction applied to multishot images. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:1273–80.2. Atkinson D, et al. Automatic correction of motion artifacts in magnetic resonance images using an entropy focus criterion. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 1997;16:903–10.

3. Manke D, et al. Novel prospective respiratory motion correction approach for free-breathing coronary MR angiography using a patient-adapted affine motion model. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:122–131.

4. Montalt-Tordera J, et al. Machine learning in Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Image reconstruction. Physica Medica. 2003; 83: 79-87

5. Chen Y, et al. AI-Based Reconstruction for Fast MRI—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Proc of the IEEE. 2022; 110( 2): 224 – 245.

6. Zeng C, et al. Review of Deep Learning Approaches for the Segmentation of Multiple Sclerosis Lesions on Brain MRI. Front Neuroinform 2020.

7. Küstner T, et al. Retrospective correction of motion-affected MR images using deep learning frameworks. Magn Reson Med. 2019; 82(4): 1527-1540.

8. Pawar K, et al. Suppressing motion artefacts in MRI using an Inception-ResNet network with motion simulation augmentation. NMR in Biomed. 2019; 35(4).

9. Tamada D, et al. Motion Artifact Reduction Using a Convolutional Neural Network for Dynamic Contrast Enhanced MR Imaging of the Liver. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2020;19(1):64-76.

10. Qi H, et al. End-to-end deep learning nonrigid motion-corrected reconstruction for highly accelerated free-breathing coronary MRA. Magn Reson Med. 2021: 86(4); 1983-1996.

Figures

Fig 1. Performance of the combined model-based and ML-based approach on simulated rigid and OOP type motion. An axial T2w brain image is shown. (A) motion free ground truth, (B) motion corrupted image, (C) ML-only processing, (D) model-based only corrected and (E) combined model-based and ML-based corrected. With model-based motion correction, residual motion artifacts still remain (red arrows). ML-based motion correction led to blurring of features (red arrowheads). Combining model-based and ML processing produced the best IQ. (F)-(J) zoomed-in image of a small region.

Fig 2. An example of the performance of the proposed combined model-based and

ML-based approach on simulated two-rest-states type motion. A sagittal T2w C-spine

image is shown. (A) motion free ground truth, (B) motion corrupted image, (C)

ML-only processing, (D) model-based only corrected, and (E) combined

model-based and ML-based corrected. With model-based motion correction and

ML-based motion correction, residual motion artifacts still remain (red arrows).

Combining model-based and ML processing produced the best IQ, though some minor

blurring was visible (red arrowhead)

Fig 3. IQ metric comparison for (A) motion type 1:

rigid and OOP motion and (B) motion type 2: two rest states. Bar chart

comparing the mean SSIM and PSNR for model-based only motion correction,

ML-only motion correction, and Model+ML combined motion correction are shown.

For both R=1 and R=2, the proposed combined model performs best and has the

highest IQ metric. Pairs with statistically significant (P<0.05)

difference are indicated using an asterisk.

Fig 4. Performance of the combined model-based and

ML-based approach on in-vivo data. An axial T2w brain image acquired in the

presence of rotation motion is shown. (A) motion corrupted image, (B)

ML-only processing, (C) model-based only corrected and (D) combined

model-based and ML-based corrected. ML-only processing did not produce good IQ,

and features appear blurred (red arrowheads). With model-based motion correction,

residual motion artifacts still remain (red arrows). Combining model-based and ML

processing produced the best IQ. (E)-(H) zoomed-in image of a small

region.

Fig 5. An example of the performance of the proposed combined model-based and

ML-based approach on in-vivo data. A sagittal T2w C-spine image is shown. (A)

motion corrupted input image, (B) ML-only processing, (C) model-based only

corrected, and (D) combined model-based and ML-based corrected. With

model-based motion correction and ML-based motion correction, motion artifacts

still remain (red arrows). Combining model-based and ML processing produced the

best IQ, though some residual motion artifacts were visible (red arrowhead).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1998