1995

Automated multi organ segmentation for 3D fetal body MRI: differences in the normal growth charts for different acquisition parameters1Department of Biomedical Engineering, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Academic Women's Health Department, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Fetal Medicine Department, GSTT, London, United Kingdom, 4Institute for Women’s and Children’s Health, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 5Centre for the Developing Brain, King's College London, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Prenatal, Segmentation

This work presents the first deep learning pipeline for segmentation of multiple body organs from motion corrected 3D ssTSE fetal MRI. It is used to compare growth charts of the normal body organ development during 21-37 week GA range for 254 fetal datasets with different acquisition protocols (field strength and TE).Introduction

T2w ssTSE fetal MRI provides superior visualisation of fetal body organs1. Application of motion correction tools based on slice-to-volume registration (SVR)2 allows reconstruction of high-resolution isotropic 3D images of fetal brain and body that provide detailed visualisation in 3D3 and can be used for 3D segmentation. However, in conventional clinical research practice, MRI-derived body organ volumetry4 is primarily based on manual segmentation in 2D planes, which is time-consuming and is affected by inter-observer bias. This is gradually being addressed by deep learning that showed promising results for segmentation of the fetal brain5 and lungs6.In this work, we present the first deep learning pipeline for segmentation of multiple body organs from motion corrected 3D ssTSE images. It is used for the assessment of potential differences in the normal organ development growth charts for different acquisition protocols.

Methods

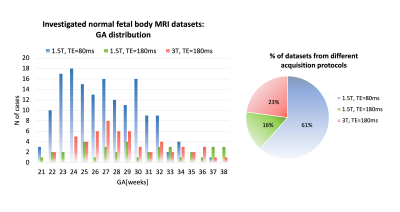

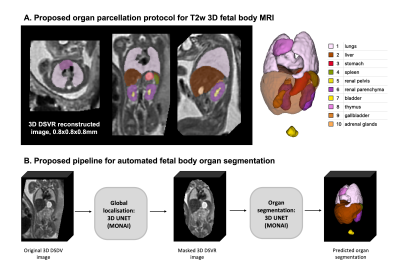

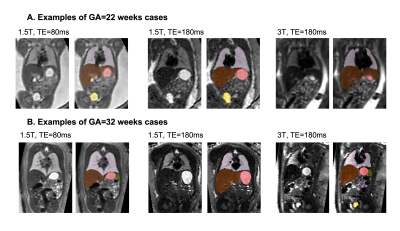

Datasets and preprocessing: The fetal MRI data include 254 datasets of 247 normal fetuses (21-38 weeks GA) acquired at St. Thomas’s Hospital, London. The datasets (Fig.1) were acquired on 1.5T and 3T Philips scanners using ssTSE sequence with TE=80ms (iFIND project REC:14/LO/1806; FIMOx project:REC:17/LO/0282) and TE=180ms (PiP project:REC:16/LO/1573; CARP project:REC:19/LO/0852). Each dataset includes 4-11 stacks with voxel size=1.25x1.25x2.5mm, slice overlap=1.25-1.5mm. The 3D reconstructions of the fetal body ROI (0.8mm isotropic resolution, standard radiological space) were performed using the automated deformable SVR (DSVR) pipeline8 in SVRTK9. The inclusion criteria were singleton pregnancy, no reported fetal or placental anomalies and visually acceptable SNR and DSVR reconstruction quality (clear visibility of organ boundaries and tissue texture).Automated segmentation of the fetal body organs: The pipeline for automated multi-label 3D segmentation of the fetal body organs in 3D DSVR MRI images (Fig.2) was implemented in Pytorch MONAI10 based on the 3D UNet11. The protocol for segmentation was defined by the experienced fetal MRI clinician (LS) and includes 10 ROIs: lungs, thymus, liver, spleen, stomach, gallbladder, renal parenchyma, renal pelvis, adrenal glands, and bladder. The training was performed in two stages. Firstly, a set of labels for 40 mixed 1.5T and 3T DSVR images was created by a combination of manual segmentation (by LS and MH) in ITK-SNAP12 and label propagation14 (lungs and thymus from the fetal thorax atlas13). These segmentations were used to train the preliminary version of the network (10000 iterations) with MONAI-based augmentation (bias field, rotations) and histogram matching. The preprocessing included masking to the body ROI (pretrained UNet8) and resampling with padding to 128x128x128 grid. Next, the network was used to segment the second set of 40 images that were manually refined and added for the final training (training:70; validation:4; 20000 iterations). The performance was tested on 6 datasets (3 1.5T / TE=80ms; 3 3T / TE=180ms) vs. the original manual labels in terms of the organ detection status (visual assessment: correct=100%, partial=50%, failed=0%) and Dice score.

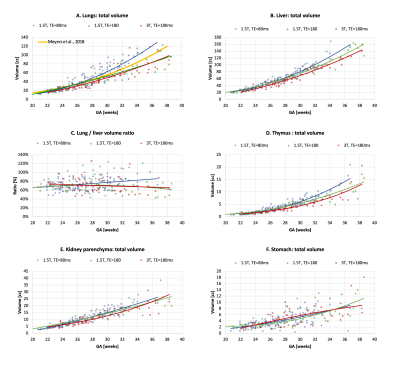

Growth chart of the fetal body organ development: We used the trained network to segment all 254 3D DSVR fetal body images from 1.5T and 3T cohorts (21-38 weeks GA range). All segmentations were reviewed. For 40 cases minor manual refinements were done for liver and kidney ROIs. The label volumes were used to generate growth charts and assess the global volumetry trends vs. different field strength and echo time.

Results

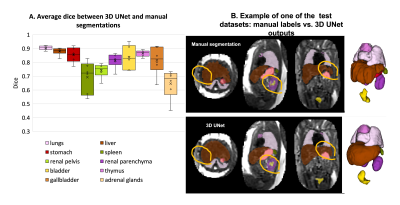

Automated segmentation of the fetal body organs: Fig.3A shows the results of the network performance on 6 test cases. UNet was able to detect all organs in all test subjects (~95% detection status due to minor partial errors). The Dice scores for different organs ranged between 0.7-0.9, with expected lower values for smaller structures. Notably, the manual labels are prone to inconsistencies and discontinuities in 3D, while UNet segmentation produces smooth boundaries (Fig.3B).Growth chart of the fetal body organ development: The growth charts generated from 254 datasets (Fig.4) demonstrate the expected15 increase in the volume for all “solid” tissue organs (e.g., liver.). Volumes of the fluid-filled organs (e.g., stomach) are not directly defined by GA (their content varies). There is a pronounced increase in variability of lung volumes after ~30 weeks and significant (p<0.001) deviation in the lung volumetry trends between the TE=80ms and TE=180ms datasets. The TE=80 values are higher while the TE=180 trends are lower than the reference lung volume formula in Meyers, et. al.16. This can be partially explained by the significantly smaller proportion of the late GA subjects for TE=80ms (only 5), limitations of UNet, inclusion of vessels and the reduced tissue intensity for the higher TE datasets (Fig.5). This emphasises the need for image harmonization, systematic large group analysis and detailed formalisation of the segmentation protocol.

Conclusions

This work introduces the first automated pipeline for multi-organ segmentation of motion corrected T2w 3D fetal body MRI. It was used to generate growth charts of the body organ development during 21-38 weeks GA range. Comparison of the volumetry trends for cohorts with different acquisitions parameters revealed systematic differences for different TE for lungs. This emphasises the need for further analysis and image harmonization, which is required for standardisation of automated MRI organ volumetry for diagnostic quantitative analysis. Our future work will focus on optimisation for a wider range of acquisition protocols and abnormal cases.Acknowledgements

We thank everyone who was involved in acquisition and analysis of the datasets at the Department of Perinatal Imaging and Health at King’s College London. We thank all participating mothers.

This work was supported by the MRC Confidence in concept (grant reference: MC_PC_19041), the European Research Council under the Wellcome Trust and EPSRC IEH award [102431] for the iFIND project, the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering at King’s College London [WT 203148/Z/16/Z)], the NIH (Human Placenta Project - grant 1U01HD087202-01), the NIHR Clinical Research Facility (CRF) at Guy’s and St Thomas’ and by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London.

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

References

1. Manganaro L, Antonelli A, Bernardo S, Capozza F, Petrillo R, Satta S, et al. Highlights on MRI of the fetal body. Radiologia Medica. 2018;123(4):271–85.

2. Uus AU, Egloff Collado A, Roberts TA, Hajnal JV, Rutherford MA, Deprez M. Retrospective motion correction in foetal MRI for clinical applications: existing methods, applications and integration into clinical practice. 2022; Br J Radiol.

3. Davidson J, Uus A, Matthew J, Egloff AM, Deprez M, Yardley I, et al. Fetal body MRI and its application to fetal and neonatal treatment: an illustrative review. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2021;5(6):447–58.

4. Story L, Zhang T, Uus A, Hutter J, Egloff A, Gibbons D, et al. Antenatal thymus volumes in fetuses that delivered <32 weeks’ gestation: An MRI pilot study. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2021 Jun 1;100(6):1040–50.

5. Payette K, de Dumast P, Kebiri H, Ezhov I, Paetzold JC, Shit S, et al. An automatic multi-tissue human fetal brain segmentation benchmark using the Fetal Tissue Annotation Dataset. Scientific Data. 2021;8(1):1–14.

6. Davidson J, Uus A, Egloff A, van Poppel M, Matthew J, Steinweg J, et al. Motion corrected fetal body magnetic resonance imaging provides reliable 3D lung volumes in normal and abnormal fetuses. Prenatal Diagnosis. 2022 May 1;42(5):628–35.

8. Uus A, Grigorescu I, van Poppel MPM, Steinweg JK, Roberts TA, Rutherford MA, et al. Automated 3D reconstruction of the fetal thorax in the standard atlas space from motion-corrupted MRI stacks for 21-36 weeks GA range. MedIA. 2022. Aug;80:102484.

9. “SVRTK: MIRTK based SVR package for fetal MRI.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/SVRTK/. [Accessed: 01-Nov-2022].

10. “MONAI framework.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/Project-MONAI/MONAI/. [Accessed: 01-Nov-2022].

11. Çiçek, Ö., Abdulkadir, A., Lienkamp, S.S., Brox, T., Ronneberger, O. (2016). 3D U-Net: Learning Dense Volumetric Segmentation from Sparse Annotation. In: MICCAI 2016. LNCS, vol 9901.

12. “ITK-SNAP tool.” [Online]. Available: http://www.itksnap.org/. [Accessed: 01-Nov-2022].

13. Uus A, Grigorescu I, Shetty A, Egloff A, Davidson J, Poppel M van, et al. Continuous 4D atlas of normal fetal lung development and automated CNN-based lung volumetry for motion-corrected fetal body MRI. In: International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM). 2021. p. 713.

14. “MIRTK package.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/BioMedIA/MIRTK/. [Accessed: 01-Nov-2022].

15. Story L, Zhang T, Steinweg JK, Hutter J, Matthew J, Dassios T, et al. Foetal lung volumes in pregnant women who deliver very preterm: a pilot study. Pediatric Research. 2020;87(6):1066–71.

16. Meyers ML, Garcia JR, Blough KL, Zhang W, Cassady CI, Mehollin-Ray AR. (2018). Fetal Lung Volumes by MRI: Normal Weekly Values From 18 Through 38 Weeks' Gestation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. Aug;211(2):432-438.

Figures