1991

Accelerated 4D flow MRI in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease1Medical Biophysics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Translational Medicine, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada, 4Department of Diagnostic Imaging, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, 5Departments of Medical Imaging and Paediatrics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Cardiovascular, Quantitative Imaging, Flow, Heart, Cardiovascular, Congenital heart disease

The application of conventional 4D flow to evaluate the hemodynamics of the heart and vessels is limited by long scan time. Recent advances aim to reduce scan time while providing sufficient accuracy. Here we investigate a 4D flow pipeline based on an undersampled 3D golden angle radial trajectory that offers reconstruction flexibility. We evaluated this technique in a cross-section of 11 pediatric patients with congenital heart disease and compared flows against conventional 2D phase contrast in target vessels.Introduction

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging plays a key role in the evaluation and monitoring of anatomy and hemodynamics in congenital heart disease (CHD). Two-dimensional (2D) velocity-encoded phase-contrast (PC) cine MRI is the primary technique used to measure blood flow velocity and volume. However, this method is limited to velocity analysis from 2D planes through targeted vessels1,2. 4D flow MRI is a CMR imaging technique that is suitable for the evaluation of complex CHD, as it provides a 3D vector field of blood flow velocities throughout the cardiac cycle. The clinical application of 4D flow has been limited historically by long scan times (more than 15 minutes)3,4. However, the last decade has seen the development of techniques (e.g. parallel imaging, compressed sensing) that have reduced scan times to approximately 5-10 minutes5,6,7. Here we investigate a 5-minute 4D flow technique, based on an undersampled 3D radial acquisition, which offers robustness to motion and flexibility in the reconstruction, and quantify its accuracy in measuring net flow in healthy adult volunteers and a cross-section of pediatric patients with CHD.Method

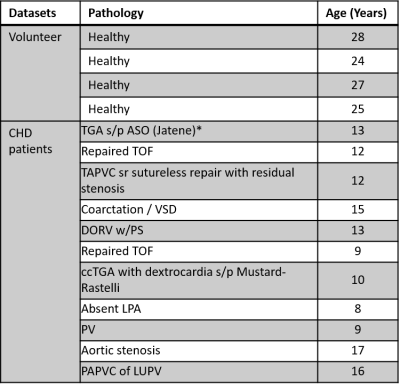

Subjects: 11 pediatric CHD patients (12.1 ± 2.9 years, M:F=8:3) and 4 healthy volunteer (26.7 ± 1.9 years, M:F=3:1) were recruited (see Table 1 for CHD types).Acquisition and reconstruction: Patients and healthy controls were scanned on a 1.5T and 3.0T MRI, respectively (Avanto and Prisma, Siemens Healthineers, Germany).

4D flow data were acquired using an internally developed sequence involving a 3D center-out radial trajectory with golden angle spoke ordering and 4-point velocity encoding. A 5-minute free-breathing scan (5 minutes and 17±1.9 seconds) with 20357±223 spokes per velocity encode was performed (~80,000 spokes total) with the following relevant parameters: VENC = 150 cm/s, number of averages = 1, TR/TE = 3.83-4.01/1.42 ms, flip angle = 8 degrees. Data were retrospectively sorted into 8 cardiac frames using the ECG signal, and without respiratory compensation. Images were reconstructed using compressed sensing with alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM) solver8 enforcing sparsity in the temporal and spatial finite difference domains (λ = 6e-7) and 20 iterations. The pipeline is implemented in Python with the SigPy library9 and run on Research IT-High Performance Computing (RIT-HPC) service at Sickkids using 8 processors and 1 Tesla-V100 GPU node. The reconstructed FOV and spatial resolution were 252x504x504 mm3 and 1.8x1.8x1.8 mm3, respectively.

For reference, 2D phase contrast was also performed in target vessels: ascending aorta (AAo), descending aorta (DAo), main/left/right pulmonary arteries (MPA/LPA/RPA), and superior vena cava (SVC). Relevant scan parameters were: VENC = 150% of expected peak velocity by vessel, TR/TE = 5.51-7.12/2.9-3.25 ms, number of averages = 2, reconstructed phases = 25, spatial resolution = 1.09-1.33 mm, slice thickness = 4.5-5 mm, flip angle = 20-25 degrees.

Flow analysis: The reconstructed 2D and 4D flow data were analyzed using commercial post-processing software (QFlow, Medis Medical Imaging Systems, the Netherlands; and cvi42, Circle Imaging, Canada respectively). A degree-3 polynomial was fit and subtracted to correct for phase background. Following phase unwrapping for the 4D flow images, regions of interest were segmented for the analysis, positioned based on the prescription of the 2D phase contrast MR slices.

Results and Discussion

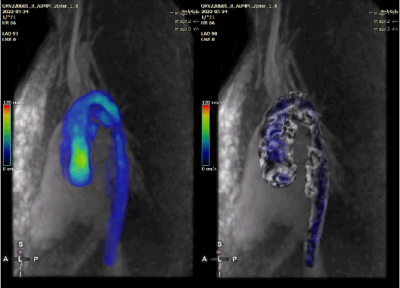

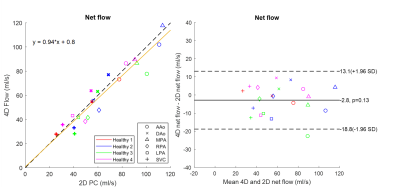

The average reconstruction time was 48.5±9.7 mintues for each dataset. One CHD case was excluded due to excessive bulk motion during the 4D flow scan. Qualitative visualizations of flow from one CHD patient are presented in Figure 1, depicting animated pathlines for a case of repaired ventricular septal defect (VSD) and coarctation of the aorta. The animation on the right panel shows that an increased flow remains at the coarctation site even after the palliative procedure. The velocity map shows the area with increased velocity in the aorta (maximum velocity was 2 m/s). Measurements by 2D phase contrast were only performed at the aortic root.Figure 2 (left panel) shows a comparison of net flow measured by radial 4D flow versus conventional 2D phase contrast in healthy volunteers. Linear regression (orange line) showed good-excellent agreement between the measurements from healthy subjects (R2 = 0.90, slope = 0.94±0.15 with 95% confidence interval, root mean square error [RMSE] = 8.29 ml/s). Figure 2 (right panel) shows the Bland-Altman comparison between 4D and 2D measurements, with a difference of 2.3±8.2 ml/s (p=0.13).

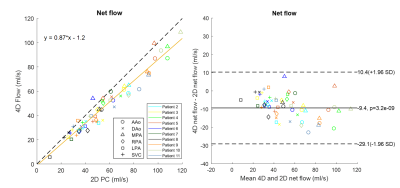

As shown in Figure 3, good correlation was also obtained between 4D vs. 2D net flows from CHD patients (R2 = 0.94, slope = 0.87±0.06 with 95% confidence interval, RMSE = 5.63 ml/s). Net flows within a given vessel varied widely between CHD patients because of differences in age and pathology. Bland-Altman analysis shows an underestimation of 4D flow measurements by 9.4±10.1 ml/s (p = 3.2e-9) in the cohort of CHD patients.

Previous studies that used motion correction, respiratory gating or longer scan times have shown similar agreement between 2D and 4D flow measurements in healthy volunteers10,11,12, and in infants with CHD using time-averaged volumetric flow imaging to keep scan times short (~3 minutes)12.

Conclusion

The proposed 4D flow method can provide retrospective in-vivo 3D quantification and visualization in 5 minutes in technically challenging clinical population. Future work will evaluate the effect of respiratory motion correction, contrast agent and field strength on flow accuracy.Acknowledgements

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) PJT 427837. We thank MR technologists Vivian Tassos and Joti Gill for their assistance with scanning, and patients and families for participating in this research.References

1. Whitehead, K. K., Harris, M. A., Glatz, A. C., Gillespie, M. J., DiMaria, M. V., Harrison, N. E., ... & Fogel, M. A. (2015). Status of systemic to pulmonary arterial collateral flow after the fontan procedure. The American journal of cardiology, 115(12), 1739-1745.

2. Geiger, J., Markl, M., Jung, B., Grohmann, J., Stiller, B., Langer, M., & Arnold, R. (2011). 4D-MR flow analysis in patients after repair for tetralogy of Fallot. European radiology, 21(8), 1651-1657.

3. Markl, M., Frydrychowicz, A., Kozerke, S., Hope, M., & Wieben, O. (2012). 4D flow MRI. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 36(5), 1015-1036.

4. Coppo, S., Piccini, D., Bonanno, G., Chaptinel, J., Vincenti, G., Feliciano, H., ... & Stuber, M. (2015). Free‐running 4D whole‐heart self‐navigated golden angle MRI: initial results. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 74(5), 1306-1316.

5. Pruitt, A., Rich, A., Liu, Y., Jin, N., Potter, L., Tong, M., ... & Ahmad, R. (2021). Fully self‐gated whole‐heart 4D flow imaging from a 5‐minute scan. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 85(3), 1222-1236.

6. Ma, L. E., Yerly, J., Piccini, D., Di Sopra, L., Roy, C. W., Carr, J. C., ... & Markl, M. (2020). 5D flow MRI: a fully self-gated, free-running framework for cardiac and respiratory motion–resolved 3D hemodynamics. Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging, 2(6).

7. Cheng, J. Y., Hanneman, K., Zhang, T., Alley, M. T., Lai, P., Tamir, J. I., ... & Vasanawala, S. S. (2016). Comprehensive motion‐compensated highly accelerated 4D flow MRI with ferumoxytol enhancement for pediatric congenital heart disease. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 43(6), 1355-1368.

8. Wahlberg, B., Boyd, S., Annergren, M., & Wang, Y. (2012). An ADMM algorithm for a class of total variation regularized estimation problems. IFAC Proceedings Volumes, 45(16), 83-88.

9. https://sigpy.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

10. Blanken, C. P., Gottwald, L. M., Westenberg, J. J., Peper, E. S., Coolen, B. F., Strijkers, G. J., ... & van Ooij, P. (2022). Whole‐Heart 4D Flow MRI for Evaluation of Normal and Regurgitant Valvular Flow: A Quantitative Comparison Between Pseudo‐Spiral Sampling and EPI Readout. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 55(4), 1120-1130.

11. Jacobs, K. G., Chan, F. P., Cheng, J. Y., Vasanawala, S. S., & Maskatia, S. A. (2020). 4D flow vs. 2D cardiac MRI for the evaluation of pulmonary regurgitation and ventricular volume in repaired tetralogy of Fallot: a retrospective case control study. The international journal of cardiovascular imaging, 36(4), 657-669.

12. Schrauben, E. M., Lim, J. M., Goolaub, D. S., Marini, D., Seed, M., & Macgowan, C. K. (2020). Motion robust respiratory‐resolved 3D radial flow MRI and its application in neonatal congenital heart disease. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 83(2), 535-548.

Figures