1989

Early Experience of Functional Fetal Lung Imaging using Low Field MRI1Centre for the Developing Brain, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences KCL, London, United Kingdom, 2Biomedical Engineering Department, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, KCL, London, United Kingdom, 3Women’s Health, KCL, London, United Kingdom, 4MR Research Collaborations, Siemens Healthcare Limited, Frimley, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Fetal, Low-Field MRI

Low field MRI for fetal imaging has the potential to be a powerful tool for prenatal diagnosis, with a favourable combination of scope for a larger bore (adding comfort and reducing claustrophobia), and lower SAR, susceptibility effects and receiver coil properties. We performed functional scans of the fetal lung to demonstrate the high image quality that can be acquired. The quantitative values of the fetal lungs (IVIM parameters, T1, T2*) calculated from the low field images match the expected values from higher field strengths reported in the literature.Introduction

Low field magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is emerging as an exciting field, especially in the perinatal realm1. The lower field strength results in less magnetic susceptibility artifacts, negating the need for shimming and advanced imaging pre-processing techniques while increasing the dynamic range for T2* relaxometry. The shorter T1 times improve image contrast and raise efficiency2. Finally, the wide bore present in low field systems makes for a more comfortable imaging experience for pregnant women. These benefits make a low field imaging system ideal for fetal imaging.As fetal lung development is critical to survival after birth, it is important to understand the functional and structural changes occurring throughout gestation. Lung volumes from MRI have been shown to be a useful prognosticator for disorders such as fetal growth restriction and congenital diaphragmatic hernia, as well as for preterm premature membrane rupture3–5. However, functional, quantitative techniques such as T1, T2* and diffusion MRI have not yet been studied in depth for the fetal lungs. The most commonly studied, fractional perfusion, using diffusion MRI and the IVIM model, has been shown to be correlated with gestational age6,7, and early low field studies have shown that diffusion measurements can be an indicator of fetal lung maturation8. Therefore, we propose to show that functional quantitative data acquired with a low field scanner is equivalent to that acquired by standard clinical scanners, and that functional sequences can be used to explore fetal lung development.

Methods

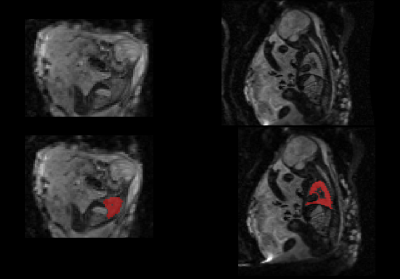

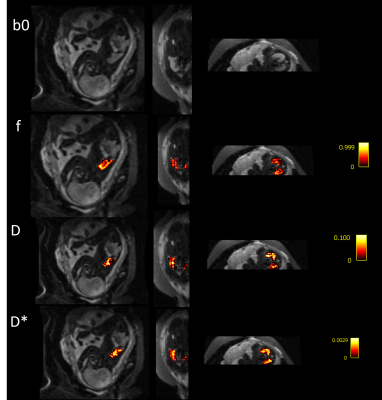

Fetal MRI was acquired as part of an ethically approved study (MEERKAT, REC 19/LO/0852, Dulwich Ethics Committee, 08/12/2021) performed between May-October 2022 at St Thomas’ Hospital, in London, UK. 38 women were scanned on a clinical 0.55T scanner (MAGNETOM Free.Max, Siemens Healthcare, Germany) using a 6-element blanket coil and a 9-element spine coil built into the table scanner. Three different types of functional sequences were acquired: diffusion MRI, T2* relaxometry and T1 relaxometry, all sharing a FOV of 400x400 mm2. Diffusion scans were acquired with a single-shot diffusion-weighted spin echo sequence (resolution=3x3x3mm3, TR= 7200ms, TE=129ms, 8 b-values between 0-1000s/mm2). Inversion-recovery data was acquired with a single-shot gradient echo sequence (resolution=4x4x4mm3, TR=3820ms, TE=80ms) and multi-echo T2* data was acquired with a single-shot gradient-echo sequence (TR=15480ms, , 5 TEs=[49–345]ms GRAPPA=2). Fetal T2* lung images were acquired at 3T (resolution: 3x3x3mm2, 4 TEs=[38-240], TR=7200ms). The images were reviewed, and cases with large amounts of motion were excluded. Example b0 images from the diffusion scan can be seen in Figure 1 overlaid with a manually segmented mask of the fetal lung.The IVIM parameter maps (fractional perfusion (f), diffusion coefficient (D), pseudo-diffusion coefficient (D*), were calculated using dmipy’s9 implementation of the bi-exponential mode . After reviewing the fit of each model, two further cases were excluded where the fit failed. The T1 and T2* maps were created by using mono-exponential fitting in an in-house tool in python. The mean of each of the parameters was calculated for each fetal lung ROI, and the relationship of all parameters with gestational age (GA) was explored. The calculated values were compared with existing literature at higher field strengths, where available. The Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) was calculated to determine the relationship of each variable with GA.

Results

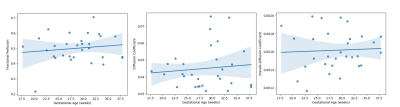

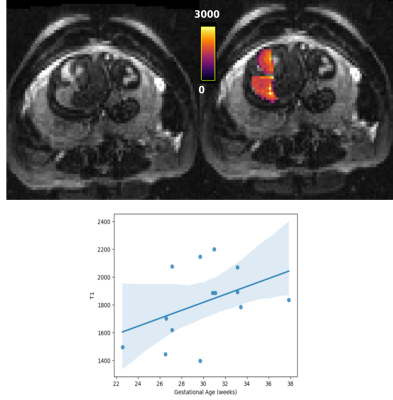

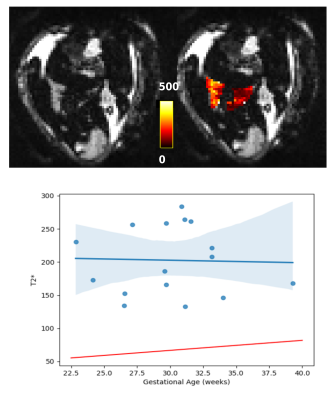

After quality checks, and importantly reviewing images for the inclusion of lungs, 30 cases with good quality fetal lung diffusion scans were selected, 14 with T1 scans, and 16 with T2* scans. Figure 2 shows an example diffusion scan and the resulting IVIM maps. Figure 3 shows the relationship between each of the diffusion parameters and GA.An example T1 image and corresponding T1 map can be seen in Figure 4. The lungs can be clearly seen in both the original image and in the T1 map. The average T1 values of the fetal lung show an increase with GA. Figure 5 shows the T2* image and corresponding T2* map of the same subject. Again, the lungs can clearly be visualized, but here when the average T2* values of all cases are compared to GA, there is not a clear trend.

Discussion and Conclusion

The presented functional contrasts on the fetal lungs illustrate that low field MRI scanners are a promising avenue for fetal MRI. The quantitative results are in-line with the literature where expected (the IVIM parameters), and deviate as expected (higher T2* values when compared to 3T). At higher field strengths, extensive pre-processing of diffusion data is required in order to correct for eddy currents and b0 distortion, and these computationally-intensive steps were not required for this low field analysis.The correlation between each of the IVIM parameters and GA is weak, whereas the literature has reported a correlation between f and GA. However, the values of each of the parameters are in the same range as reported on by the existing fetal lung IVIM literature acquired at 1.5T and 3T at the higher GA6,7. The lack of motion correction may explain this deviation especially at the lower GA, which is where most of the excluded motion and discrepancies with the literature lie. Future analysis should incorporate motion correction in order to improve the number of cases included in such a study, especially at lower GAs.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all pregnant women and their families for taking part in this study. The authors thank the research midwives and radiographers for their crucial involvement in the acquisition of these datasets. This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Collaboration in Science grant [WT201526/Z/16/Z], a UKRI FL fellowship and by core funding from the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering [WT203148/Z/16/Z]. The views presented in this study represent these of the authors and not of Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust.References

1. Aviles, J. et al. A Fast Anatomical and Quantitative MRI Fetal Exam at Low Field. in Perinatal, Preterm and Paediatric Image Analysis (eds. Licandro, R., Melbourne, A., Abaci Turk, E., Macgowan, C. & Hutter, J.) 13–24 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2022). doi:10.1007/978-3-031-17117-8_2.

2. Hori, M., Hagiwara, A., Goto, M., Wada, A. & Aoki, S. Low-Field Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Invest. Radiol. 56, 669–679 (2021).

3. Corroenne, R. et al. Cost-effective fetal lung volumetry for assessment of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 260, 22–28 (2021).

4. Moradi, B. et al. Comparison of fetal lung maturation in fetuses with intrauterine growth restriction with control group, using lung volume, lung/liver and lung/muscle signal intensity and apparent diffusion coefficient ratios on different magnetic resonance imaging sequences. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. Off. J. Eur. Assoc. Perinat. Med. Fed. Asia Ocean. Perinat. Soc. Int. Soc. Perinat. Obstet. 1–9 (2021) doi:10.1080/14767058.2021.2008349.

5. Messerschmidt, A. et al. Fetal MRI for prediction of neonatal mortality following preterm premature rupture of the fetal membranes. Pediatr. Radiol. 41, 1416–1420 (2011).

6. Ercolani, G. et al. IntraVoxel Incoherent Motion (IVIM) MRI of fetal lung and kidney: Can the perfusion fraction be a marker of normal pulmonary and renal maturation? Eur. J. Radiol. 139, 109726 (2021).

7. Jakab, A. et al. Microvascular perfusion of the placenta, developing fetal liver, and lungs assessed with intravoxel incoherent motion imaging. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging JMRI 48, 214–225 (2018). 8. Moore, R. J., Strachan, B., Tyler, D. J., Baker, P. N. & Gowland, P. A. In vivo diffusion measurements as an indication of fetal lung maturation using echo planar imaging at 0.5T. Magn. Reson. Med. 45, 247–253 (2001).

9. Fick, R. H. J., Wassermann, D. & Deriche, R. The Dmipy Toolbox: Diffusion MRI Multi-Compartment Modeling and Microstructure Recovery Made Easy. Front. Neuroinformatics 13, (2019).

Figures