1988

Fetal Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance: A Comparison of Doppler Ultrasound and Self-Gating Techniques1Radiology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, United States, 2Technische Universitat Munchen, Munich, Germany, 3Cardiology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Fetal, Cardiovascular

Fetal cardiovascular magnetic resonance requires an accurate measure of the fetal heart rate for cine image acquisitions. In this work, we compared the use of Doppler ultrasound with a self-gating technique in 8 subjects. Images were acquired in the axial and short-axis orientations of the fetal heart, and the images were compared with qualitative scoring, heart rate analysis, and ventricular volumes. It was found that the techniques had only minor differences demonstrating the potential use of retrospective self-gating in the clinic, as it reduces workflow complexity and may lead to shorter exam times for pregnant women.Background

Congenital heart disease (CHD) occurs in about 0.7-0.9% of live births worldwide (1), and despite widespread ultrasound screening in the United States up to 65% of cases experience delayed or missed detection (2), depending on the defect type. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) is widely used in pediatric and adult populations, and cine CMR can complement echocardiography (3); however, its use is hampered by the requirement of an accurate fetal heart rate for gating the cardiac motion in cine acquisitions. Three potential candidates for detecting the fetal heart rate are Doppler ultrasound (DUS) (4), metric optimized gating (5), and self-gating (SG) methods (6). In this work we compare the performances of DUS and SG techniques with qualitative and quantitative measures.Methods

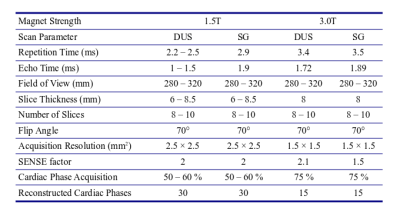

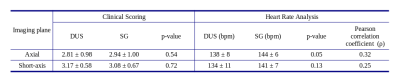

Eight pregnant patients (n=6, 1.5T) and healthy volunteers (n=3 (1 retrospectively excluded), 3.0T) (age: 31.6 ± 6.4 years, gestational age (GA): 33.2 ± 1.6 weeks) with informed consent underwent fetal CMR exams at Children’s Hospital Colorado. One volunteer was dropped due to a failure in acquiring adequate DUS images due to poor gating. Philips Ingenia scanners (1.5 and 3.0T) were used in the acquisition of axial (AX) and short-axis (SA) images of the fetal heart, with patient breath-holds (BH) of 6-12 s for 1-2 slices / BH. Stacks of 6-10 slices were prescribed in each orientation to have complete anatomical coverage. A smart-sync DUS device (Northh Medical, Hamburg, DE) was positioned and used to measure the fetal heart rate. Acquisitions were conducted for the DUS images first, and then SG slice locations were prescribed to match the DUS positions as close as possible. Images were reconstructed to 0.9-1.0 mm in plane, with 30 (1.5T) or 15 (3.0T) cardiac phases respectively. DUS triggered images were reconstructed inline by the scanner, with SG images triggered respectively by setting the fetal heart rate as determined by using independent component analysis of the center of k-space (7). The full imaging protocol is listed in Table 1. Two clinicians, blinded to the image types, scored the images on a 4-point scale: 1 (poor, borders cannot be traced); 2 (fair, borders are traceable but blurred); 3 (good, border are slightly blurred); and 4 (excellent, borders are sharp). Scores were compared with a paired, two-tailed Student’s t-Test to examine group differences between the means. Median DUS heart rates were calculated from the physiology logs of the scanner for each DUS acquisition and compared with t-Tests and Pearson correlation coefficients to the SG heart rates. Two subjects with SA stacks for the entire fetal heart with limited motion artifacts were selected for heart segmentations and ventricular volume measurements using open-source FSL software (8).Results

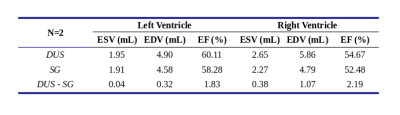

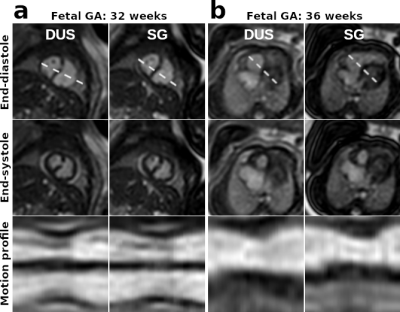

Figure 1 shows example cine images from two subjects acquired with DUS and SG techniques. Discrepancies are minor or indistinguishable, despite fetal movement between the acquisitions and the difficulties in matching prescriptions. Figure 2 shows the images at end-systole, end-diastole with motion profiles from two subjects, with only minor or indistinguishable differences between the image pairs. Table 2 has the clinicians’ scores and heart rate analysis for the two techniques for both AX and SA orientations. There were no statistically significant differences between the scoring group means. For the heart rates, we observe that there is a small bias between the calculated DUS heart rates and those determined by the SG technique; however, over estimation of the heart rate by SG is about 6 bpm (≤ 5 %) and does not impact the image quality. The ventricular volumes and ejection fractions comparisons between the techniques are in Table 3, with the DUS and SG images both reporting similar measurements.Conclusions

In theory, DUS has an advantage over the SG technique in that it measures the actual fetal heart rate, and thus captures any deviations in real time. In practice however, these differences are minimal, and the SG technique suffers little, if any, degradation in image quality as qualitatively scored in this study. The quantitative measurements indicate some differences in fetal heart rate; however, these are relatively minor and overall, there is good agreement between the DUS and SG images. Fetal heart rate is also expected to vary in normal fetal development; thus, differences in the detected heart rates may be a reflection of this point. A potential pitfall of the DUS method is that the device may lose signal due to device connectivity, fetal motion, or triggering problems, thus requiring either repeat acquisitions or device repositioning – both lengthen examination time. The SG technique does not require any additional hardware leading to a more streamlined workflow.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Hoffman JIE, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2002;39:1890–1900 doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01886-7.

2. Quartermain MD, Pasquali SK, Hill KD, et al. Variation in Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease in Infants. Pediatrics 2015;136:e378–e385 doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3783.

3. N Saleem S. MRI of Fetal Heart Using Balanced Steady-State Free Precession (SSFP) Sequence: Feasibility of Image Analysis Using Anatomical Segmental Approach for Congenital Heart Disease.; 2008.

4. Kording F, Yamamura J, de Sousa MT, et al. Dynamic fetal cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging using Doppler ultrasound gating. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 2018;20:17 doi: 10.1186/s12968-018-0440-4.

5. Roy CW, Seed M, van Amerom JFP, et al. Dynamic imaging of the fetal heart using metric optimized gating. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2013;70:1598–1607 doi: 10.1002/mrm.24614.

6. Chaptinel J, Yerly J, Mivelaz Y, et al. Fetal cardiac cine magnetic resonance imaging in utero. Sci Rep 2017;7:15540 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15701-1.

7. von Kleist H, Copeland N, Grant PE, Tworetzky W, Powell AJ, Moghari MH. Fetal Cardiac MRI using Self-gating with a Cartesian K-space Trajectory. In: Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med 27 (2019). Montreal, CA; 2019.

8. Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage 2004;23 Suppl 1:S208-19 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051.

Figures