1987

Comprehensive evaluation of bicuspid aortic valve structure, hemodynamics, and tissue characterization in mice using MRI

El-Sayed H. Ibrahim1, John LaDisa1, and Joy Lincoln1

1Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, United States

1Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Cardiovascular, Valves, congenital heart disease

Bicuspid Aortic Valve (BAV) is the most common congenital heart disease affecting 1-2% of all live births. Current clinical management includes periodic surveillance of aortic valve dysfunction, and only when the valve becomes stenotic is intervention recommended, which includes surgical procedures that come with insuperable long-term outcomes. We optimized a small-animal MRI protocol for comprehensive evaluation of the BAV structure, function, flow pattern, and tissue characterization. Children and adolescents with BAV would benefit from this comprehensive assessment of their risk profile during early stages of the disease to better predict outcomes and clinical management strategies.Introduction

Bicuspid Aortic Valve (BAV) is the most common congenital heart disease affecting 1-2% of all live births and arises due to the abnormal fusion of two of the three valve cusps during embryonic development. However, it is not the primary structural malformation that enforces the need for treatment in young adults, but the accelerated development of life-threatening critical aortic stenosis (AS) as a result of premature calcification in up to 50% of patients; particularly those with right and non-coronary (R/NC) cusp fusion. Despite the anticipated onset of calcification and AS in children and adolescents with BAV, current clinical management includes periodic surveillance of aortic valve dysfunction, and only when the valve becomes stenotic is intervention recommended. This includes balloon valvuloplasty for high-risk operable patients, or transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement for patients at low or intermediate operative risk; however, relief is variable and largely suboptimal, and surgical procedures come with insuperable long-term outcomes. Therefore, children and adolescents with BAV would benefit from a comprehensive non-invasive evaluation of their risk profile during early stages of disease to better predict outcomes and clinical management strategies, which is investigated in this study on a genetic mouse model of BAV.Methods

The developed imaging protocol and pulse sequences were optimized on a small-animal Bruker 9.4T MRI scanner. The protocol included sequences for imaging valvular structure, function, flow pattern, and tissue characterization for comprehensive assessment of BAV in a genetically modified mouse model (Nfatc1cre;Exoc5fl/+). Proper animal setup is essential for ensuring adequate image quality and avoiding artifacts. Three-lead ECG patch electrodes were used due to their better performance compared to needle electrodes. The ECG wires were twisted and run along the center of the magnet bore to minimize signal noise. Valve structure and function information was obtained using cine imaging with either ECG gating or retrospective intra-gating, where the latter allows for 3D imaging capability with improved temporal and spatial resolutions, albeit at the cost of increased scan time. Optimized imaging parameters for cine imaging are as follows: FLASH sequence, slice thickness = 0.8 mm, TR = 7.6 ms, TE = 2.7 ms, matrix = 145x192, FOV = 25 mm, readout bandwidth = 385 Hz/pixel, # cardiac phases = 14-50, slip angle = 10°, # averages = 1. Blood flow pattern through the valve was obtained using phase-contrast (PC) imaging with minimum repetition time (TR) to improve temporal resolution. Optimized imaging parameters for PC imaging are as follows: 2D ECG-gated FLASH sequence, slice thickness = 0.8 mm, TR = 7.4 ms, TE = 3 ms, matrix = 176x176, FOV = 25 mm, readout bandwidth = 338 Hz/pixel, # cardiac phases = 12, slip angle = 15°, # averages = 6, VENC = 250 cm/s. Finally, multicontrast T1/T2/PD weighted spin-echo sequences were used to assess valvular tissue characterization. Optimized imaging parameters for T1-weighted imaging are as follows: ECG-gated RARE sequence, slice thickness = 0.8 mm, TR = 500 ms, TE = 9 ms, matrix = 125x125, FOV = 25 mm, readout bandwidth = 769 Hz/pixel, slip angle = 90°, # averages = 1. The imaging parameters for T2-weighted imaging were the same as T1-weighted imaging, except for: TR = 2500ms, TE = 20 ms, readout bandwidth = 340 Hz/pixel. The imaging parameters for PD-weighted imaging were the same as T2-weighted imaging, except for: TR = 2500ms, TE = 9 ms. The multicontrast imaging parameters were optimized based on the animal’s heart and respiratory rates to acquire data during late diastole with trigger delay ~ 80 ms during minimal valve motion. Circle cvi42 software was used to process the resulting images.Results

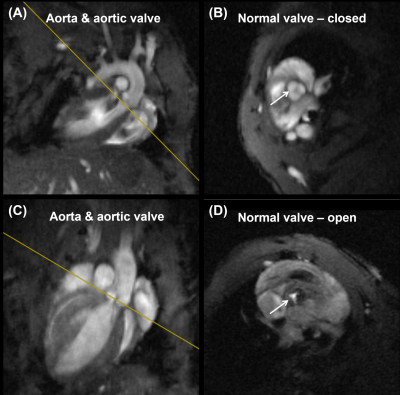

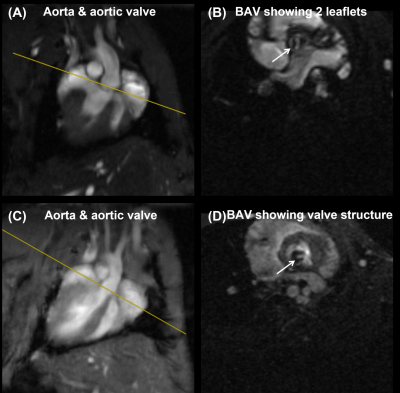

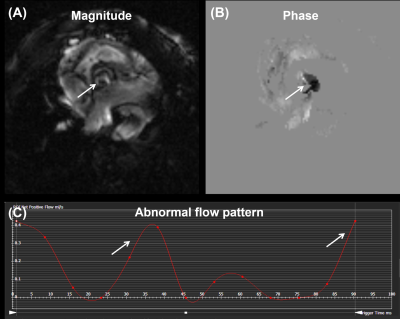

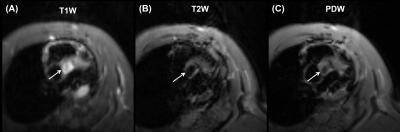

The optimized protocol produced clinically useful images in a reasonable scan time (1-2 hours depending on selected pulse sequences and type of acquisition (2D vs 3D)). Figure 1 shows the aorta and cross-sections of normal tricuspid aortic valve during diastole (valve closed) and systole (valve open). Figure 2 shows a cross-section of BAV in two mice, showing clearly the bicuspid formation as well as abnormal valve structure. Figure 3 shows PC magnitude and phase images across the aortic valve and generated flow pattern in BAV, which is distinguished from that in normal valve. Figure 4 shows multicontrast T1, T2, and PD weighted images of the aortic valve, where different signal intensities in the images can be used to study valve tissue composition, e.g., lipid, fat, edema, and calcification.Conclusions

The developed optimized MRI protocol provides complementary cardiovascular information for biomechanical assessment of BAV. A comprehensive biomechanical assessment of BAV prior to the onset of calcification will allow for exploring opportunities to improve early diagnoses by predicting the temporal onset of calcification in those most at risk based on imaging data and to create assays that track the molecular and cellular mechanisms. Therefore, children and adolescents with BAV would benefit from this comprehensive assessment of their risk profile during early stages of the disease to better predict outcomes and clinical management strategies.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Siu et al. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010; 55:2789–2800

2. Teekakirikul et al. HGG Adv. 2021; 2(3):100037

3. Kandail et al. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2018; 86:131-142

4. Yassine et al. Front. Physiol. 2017;8:687

5. Choudhury et al. Atherosclerosis. 2002;162(2):315-21

Figures

Figure 1. Normal

tricuspid aortic valve showing (A,B) valve closed during diastole and (C,D)

valve open during systole (arrows). Note normal tricuspid aortic valve

structure.

Figure 2. Two examples of

bicuspid aortic valve (valve), showing (A,B) the bicuspid structure (arrow) and

(C,D) abnormal valve structure (arrow).

Figure 3. (A) Magnitude

and (B) phase images showing a cross section of bicuspid aortic valve (BAV).

(C) Abnormal blood flow pattern in BAV shows multiple peaks (arrows).

Figure 4. Multicontrast

(A) T1 weighted, (B) T2 weighted, and (C) proton density (PD) weighted images of

bicuspid aortic valve (arrows). The images show different signal intensities

that can be used for tissue characterization of BAV.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1987