1979

Age matters: radiofrequency heating of epicardial and endocardial electronic devices in adults and children varies with body size and lead length1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, United States, 2Department of Radiology, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States, 3Division of Cardiology, Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States, 4Division of Medical Imaging, Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States, 5A. A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 6Center for Cardiovascular Innovation, Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Heart, Safety, Implants

Children with congenital heart defects often have life-sustaining indications for an epicardial cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED). However few data exist on endocardial systems in children. Additionally, the FDA has never approved an epicardial system as MRI-Conditional due to limited data on potential heating risk. To provide evidence-based knowledge on RF-induced heating of CIEDs in children and adults with epicardial and endocardial leads of different lengths, we recorded the temperature increase of 120 clinically relevant trajectories positioned into adult and pediatric phantoms. Our results highlight the need for age and device-specific assessments of MRI safety in children with CIEDs.Introduction

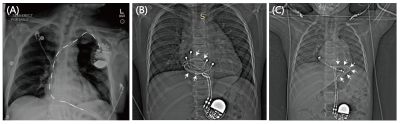

At least 75% of patients who receive a cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) will require MRI during their lifetime1. MR-conditional endocardial CIEDs have been approved for adults, where the implantable pulse generator (IPG) is placed in the pectoral region and leads are passed through the subclavian vein to reach the interior of the heart. Most children, however, receive an epicardial CIED due to their smaller anatomy or complex vasculature, where the IPG is placed in the abdomen and leads are directly sewn to the myocardium (Figure 1). While the 2021 PACES guideline made a class IIb recommendation that MRI of pediatric patients with epicardial or abandoned leads be considered individually based upon their risk/benefit ratio, no guidance is available on how to quantify those risks2. However, due to limited data availability, children’s hospitals default to either refusing MRI service to children with CIEDs or scanning patients based on results from adult studies that have limited applicability in pediatrics. We argue that improvements can be made to the current guidelines and that the decision whether to scan children with CIEDs should be made on an individual basis.Method

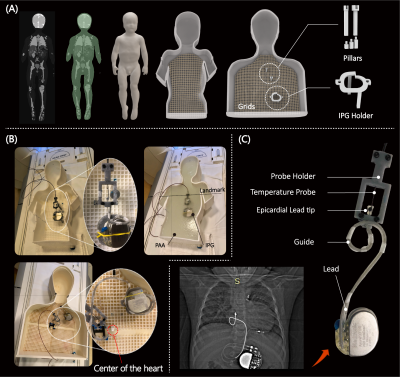

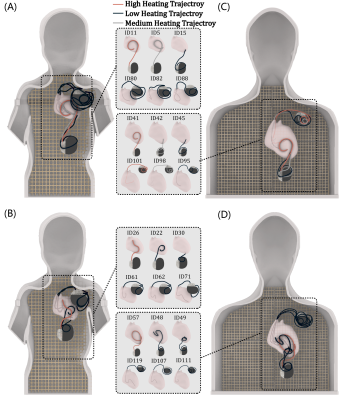

We custom-made human-shaped phantoms that mimic the silhouette of an average-sized adult and a twenty-nine-month-old child. Phantoms were filled with polyacrylamide (PAA) gel (22 L for the adult and 9 L for the pediatric phantom) with a conductivity of σ = 0.47 S/m and relative permittivity of εr = 88 representing dielectric values of average tissue (Figure 2A). We reviewed chest X-rays and computed tomography (CT) images of 200 adult and pediatric patients with epicardial and endocardial CIEDs to create representative device trajectories. Our Institutional Review Board approved the retrospective use of patient imaging data for the purpose of modeling and safety assessment. To enhance reproducibility, we designed and 3D printed trajectory guides which helped route the leads along patient-derived trajectories and keep them securely in place during the experiments, similar to our previous works3,4 (Figure 2C). 120 epicardial and endocardial lead trajectories of varying lead lengths (15, 25, 35 cm epicardial leads and 35, 45, and 58 cm endocardial leads) were positioned into the adult and pediatric phantoms following clinically relevant trajectories based on patient images (Figure 2B & Figure 3). The temperature increase was recorded using MR-compatible fiber optic probes secured at the tip of the lead. RF exposure was performed in a 1.5 T Siemens Aera scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with the phantoms positioned such that the chest was at the isocenter and using a high-SAR T1-weighted turbo spin echo sequence (TE = 7.3 ms, TR = 897 ms, B1+ = 5 µT, AT = 280 s).Results

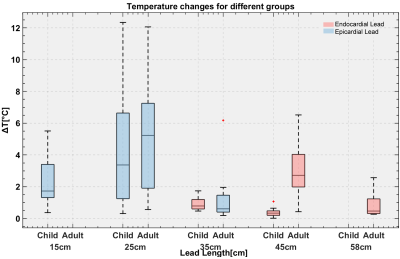

There was significantly higher RF heating of epicardial leads compared to endocardial leads in the pediatric phantom (p<0.001); however, there was no significant difference between epicardial and endocardial leads in the adult phantom (p=0.24). The maximum RF heating was observed to be ~12 °C which occurred for the 25-cm epicardial lead. For a 10-minute scan, this will be equivalent to the cumulative thermal dose of CEM43°C = 1280 minutes. This is high enough to cause necrosis in pig muscles5. This is concerning, as younger children — with thin hearts which are less tolerant to thermal injury — are more likely to receive shorter leads (i.e., 25 cm) as opposed to longer leads (e.g., 35 cm). Therefore, RF safety studies of epicardial leads in older children and young adults should not be offhandedly generalized to all children. In contrast, endocardial leads in the pediatric phantom generated significantly less RF heating than endocardial leads in the adult phantom (0.6 ± 0.4 °C vs. 2.0 ± 1.8 °C, p<0.001).Discussion and Conclusion

Tissue heating from radiofrequency (RF) excitation fields remains a major issue. Two factors determine the severity of RF heating of implanted CIEDs: the patient’s body size and the lead’s length/trajectory6-8. Because the position, orientation, trajectory, and length of the lead within the human body determine the degree to which the MRI electric field couples with the lead, RF safety in children must be assessed on an age-specific basis. Due to their smaller anatomy, endocardial leads in children often have more loops around the IPG compared to the same devices implanted in adults. Reducing the straight portion of an elongated lead has been shown to reduce RF heating in neuromodulator devices9, which explains why endocardial leads generated significantly lower RF heating in children. Also, younger children are more likely to receive shorter epicardial leads (e.g., 25 cm). The RF field’s half-wavelength in the tissue is ~26 cm at 64 MHz, which explains the excessive heating of 25 cm leads whose length approaches the resonance length. We demonstrate that endocardial leads may be lower risk for hospitals to start imaging children with CIEDs, moving the field away from a blanket ban on children with CIEDs. Additionally, our epicardial data highlights the need for age and device-specific assessment of MRI safety in children with CIEDs. Specifically, safety studies in adults should not be offhandedly interpolated to children who receive different CIED lead lengths and follow different trajectories.Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH grant R01EB030324.References

1. Kalin R, Stanton MS. Current clinical issues for MRI scanning of pacemaker and defibrillator patients. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28(4):326-328.

2. Writing Committee M, Shah MJ, Silka MJ, et al. 2021 PACES Expert Consensus Statement on the Indications and Management of Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Devices in Pediatric Patients: Developed in collaboration with and endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC) Endorsed by the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), the Indian Heart Rhythm Society (IHRS), and the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS). JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2021;7(11):1437-1472.

3. Golestanirad L, Kazemivalipour E, Keil B, et al. Reconfigurable MRI coil technology can substantially reduce RF heating of deep brain stimulation implants: First in-vitro study of RF heating reduction in bilateral DBS leads at 1.5 T. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0220043.

4. Bhusal B, Stockmann J, Guerin B, et al. Safety and image quality at 7T MRI for deep brain stimulation systems: Ex vivo study with lead-only and full-systems. PLoS One. 2021;16(9):e0257077. 5. van Rhoon GC, Samaras T, Yarmolenko PS, Dewhirst MW, Neufeld E, Kuster N. CEM43°C thermal dose thresholds: a potential guide for magnetic resonance radiofrequency exposure levels? European radiology. 2013;23(8):2215-2227.

6. Mattei E, Triventi M, Calcagnini G, et al. Complexity of MRI induced heating on metallic leads: Experimental measurements of 374 configurations. BioMedical Engineering OnLine. 2008;7(1):11.

7. Nordbeck P, Weiss I, Ehses P, et al. Measuring RF-induced currents inside implants: Impact of device configuration on MRI safety of cardiac pacemaker leads. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(3):570-578.

8. Van Den Bergen B vdBC, Kroeze H, Bartels L, Lagendijk J. The effect of body size and shape on RF safety and B1 field homogeneity at 3T. 2006.

9. Golestanirad L, Kirsch J, Bonmassar G, et al. RF-induced heating in tissue near bilateral DBS implants during MRI at 1.5 T and 3T: The role of surgical lead management. Neuroimage. 2019;184:566-576.

Figures