1977

Quantitative MRI Measurement of Lung Development in Early Onset Fetal Growth Restriction1King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2University College London, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Fetus

Fetal growth restriction (FGR) occurs when a fetus does not reach its full growth potential, predisposing the fetus to long-term impacts on lung function at birth and into childhood. We propose a novel model of fetal lung tissue based on combined diffusion and relaxation and apply this to a cohort of FGR and appropriately grown controls. We show differences in lung model parameters in FGR relative to controls and with gestational age. We also link these parameters to measurement of feto-placental oxygenation. This methodology could potentially provide a non-invasive method to assess fetal lung development.Introduction

Fetal growth restriction (FGR)[1,2] occurs when a fetus fails to reach its genetic growth potential and is most commonly linked to placental insufficiency secondary to inadequate spiral artery remodeling in early pregnancy[3]. FGR increases the risk of stillbirth[4], prematurity, and predisposes the surviving infant to later long-term health sequalae[5,6]. FGR affects lung development in utero, increasing the risk of long-term respiratory consequences. Imaging capable of diagnosing the degree of pulmonary hypoplasia in utero would improve prenatal counselling and optimise management decisions. MRI has been shown to measure differences in the fetus and placenta with FGR compared to appropriately grown controls[7–9]. Cannie[10] showed differences in lung parameters estimated using MRI between structurally normal fetuses and fetuses with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH). It has also been shown that fetal lung tissue has a much lower tissue T2 in fetuses with CDH[11]. MR imaging has the potential to reveal information about lung development. If lung function can be predicted, this may influence management of the pregnancy, for instance supporting a decision to deliver early, or providing information for the later neonatal setting[9,10]. Here we propose a new MR model-fitting method designed to measure features of lung development in utero. The method fits a two-compartment model to measure how the relative contributions of lung parenchyma and amniotic fluid change with pregnancy.Methods

Data Acquisition MRI data was acquired from 16 appropriately grown control cases (GA at scan 28±3wks, EFW 1424±425g) and 20 early-onset FGR (GA at scan 29±2wks, EFW 717±313g). FGR was defined in accordance to a Delphi censensus[2].MRI data was acquired with a 1.5T Siemens Avanto under free-breathing12. Data was acquired as a combination of mixed combinations of 7 b-values and 9 echo-times at b-values [0,50,100,150,200,400,600s.mm-2] and T2 relaxometry measurements at echo times [77,90,120,150,180,210,240,270,300ms]. The voxel resolution was 1.9x1.9x6mm. All participants gave written informed consent and data was anonymised. Manual segmentation of the regions of interest were performed[13]. Statistical testing was carried out with Students t-test and Pearson Correlation, significance was set below 0.05.MRI Model Fitting Diffusion MRI is sensitive to the translational mobility of water molecules in tissue. The lung parenchyma consists of the tissue in the lung involved in gas exchange, such as the alveoli[14]. However, in the womb the fetus takes fluid into its airways which fills the lungs. This lung fluid has very similar properties to the amniotic fluid. To investigate the lung tissue we propose a novel model that assumes that the lung tissue is comprised of two key compartments with differing diffusion and relaxation processes 1) an a

mniotic fluid filled respiratory tract and 2) the lung parenchyma. We assume that the vascular component of the lung tissue is small and do not model this component. Our model is described with the following equation:

$$S(b,t) = S_0\left[ \lambda e^{-bd_p-t/T2_p} + (1-\lambda)e^{-bd_a-t/T2_a} \right]$$

The variables represent the known b-values b, and echo-times t, and the estimated baseline signal S0, tissue T2 values (T2a and T2p for the amniotic fluid and parenchyma respectively) , lung parenchyma diffusivity dp, lung fluid diffusivity da and parenchymal volume fraction λ. To ensure a stable fitting, lung fluid diffusivities are restricted based on fitted results from pure fluid regions (fetal bladder). Placental MRI was fitted using a previously described method to estimate feto-placental oxygen saturation from combined diffusion and relaxation MRI data[15].

Results

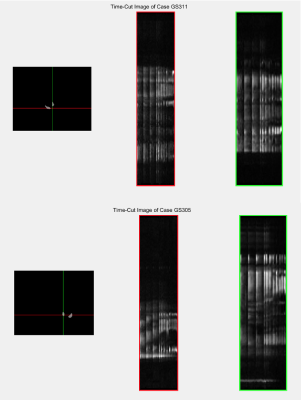

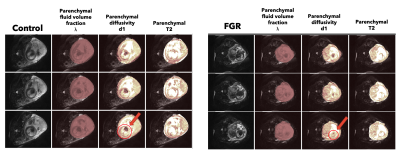

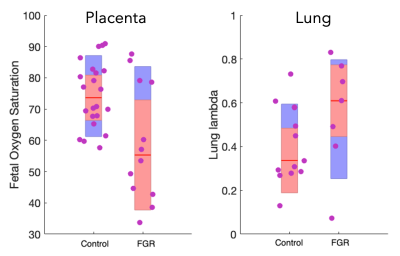

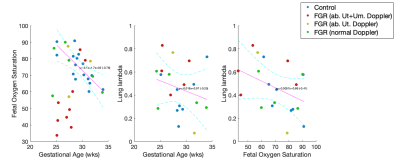

Figure 1 shows timecut motion analysis. Motion inspection in this case revealed 10 datasets where fetal lung analysis was compromised and these were removed from further analysis. Multiparametric maps are shown in Figure 2 for the fetal lung segmentations, the columns display the MRI slice, the parenchymal fluid fraction λ, diffusivity dp and the T2p of the lung tissue from left to right for one control case and one FGR case Figure 3 shows the group difference in the lung parenchymal volume fraction (lambda) between the control group and FGR. This difference is found to be significant. Statistical testing of the group with motion corrupted data removed shows λ to be significantly higher in FGR than controls whereas parenchymal T2, dp and da are not significantly different. Figure 4a shows how feto-placental SO2 and lung parenchymal volume fraction varies with gestational age in controls (r=-0.77) and in FGR with a significant correlation. Lung λ (Figure 4b) only has a weak correlation with gestational age across all subjects (r=-0.24), but the correlation of lung λ (Figure 4c) with feto-placental oxygenation is moderate (r=-0.41), suggesting a link between these two parameters and one that is independent of gestational age.Discussion

We have developed a novel fetal lung model with the potential for investigating lung development in utero. These findings are consistent with previous results investigating the fetal lung[10,11]. Our results show that fetuses with growth restriction have higher tissue volume fractions (but smaller total lung volume) than appropriately grown control cases. Previous work has shown that placental insufficiency promotes hypoxia in fetuses, creating a risk for fetal development in the womb. Alongside other results from MRI or antenatal assessment, this model could be predictive of respiratory outcome in fetuses at risk of pulmonary hypoplasia, including those with FGR.Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Wellcome Trust (210182/Z/18/Z and Wellcome Trust/EPSRC NS/A000027/1) and the Radiological Research Trust. The funders had no direction in the study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation or publication decision. We would like to thank Dr Magda Sokolska and Dr David Atkinson for their invaluable help and advice acquiring the imaging data for this study.References

References1. Reinebrant, H. E. et al. Making stillbirths visible: a systematic review of globally reported causes of stillbirth. BJOG 125, 212–224 (2018).

2. Gordijn, S. J. et al. Consensus definition of fetal growth restriction: a Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol (2016) doi:10.1002/uog.15884.

3. Burton, G. J. & Jauniaux, E. Pathophysiology of placental-derived fetal growth restriction. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.577 (2018).

4. Lawn, J. E. et al. Stillbirths: Where? When? Why? How to make the data count? The Lancet (2011) doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62187-3.

5. Nardozza, L. M. M. et al. Fetal growth restriction: current knowledge. Arch Gynecol Obstet 295, 1061–1077 (2017).

6. Pike, K., Jane Pillow, J. & Lucas, J. S. Long term respiratory consequences of intrauterine growth restriction. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 17, 92–98 (2012).

7. Zhu, M. Y. et al. The hemodynamics of late-onset intrauterine growth restriction by MRI. Am J Obstet Gynecol (2016) doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.004.

8. Sinding, M. et al. Placental T2* measurements in normal pregnancies and in pregnancies complicated by fetal growth restriction. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology (2016) doi:10.1002/uog.14917.

9. Aughwane, R. et al. MRI Measurement of Placental Perfusion and Oxygen Saturation in Early Onset Fetal Growth Restriction. BJOG 128, 337–345 (2020).

10. Cannie, M. et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI in lungs of normal fetuses and those with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 34, 678–686 (2009).

11. Cannie, M. et al. T2 quantifications of fetal lungs at MRI-normal ranges. Prenat Diagn 31, 705–711 (2011).

12. Aughwane, R. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging measurement of placental perfusion and oxygen saturation in early‐onset fetal growth restriction. BJOG 128, 337–345 (2021).

13. Yushkevich, P. A. et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: Significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage 31, 1116–1128 (2006).

14. Rehman, S. & Bacha, D. Embryology, Pulmonary. (2022).

15. Melbourne, A. et al. Separating fetal and maternal placenta circulations using multiparametric MRI. Magn Reson Med 81, 350–361 (2019).

Figures