1954

Investigating the Use of Statins in a Juvenile Photothrombotic Rat Stroke Model1Translational Medicine, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Neurosciences and Mental Health, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Department of Medical Imaging, The University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Stroke, Brain

Pediatric stroke remains a significant cause of lifelong neurological impairment and morbity. Treatment options and our understanding of stroke evolution in the developing brain, especially beyond the peri- and neonatal period, is still limited. By using a photothrombotic juvenile rat stroke model and quantitative MRI, we were able to assess stroke and blood-brain barrier damage following the use of atorvastatin from the hyper acute to chronic stages following acute ischemic stroke. Findings support a reduction in lesion volume within the statin group with no significant changes to BBB damage.Introduction

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) in childhood remains a significant cause of lifelong neurological impairment and ranks as one of the top ten causes of death in childhood1,2. While current research in pediatric stroke over the past decades has revealed new treatment practices, risk factors, and neurological outcomes, there remains a clinical gap in our understanding of the mechanisms of stroke in the developing brain, as well as limited therapeutic options for prevention and treatment, especially beyond the perinatal or neonatal period1,2. It is important, therefore, to further investigate the pathophysiology during childhood AIS, which can be facilitated through an animal model. The photothrombotic ‘ring’ model is a method that causes ischemic damage within a given cortical area by photochemically induced platelet occlusion of cortical vasculature3. This technique facilitates reproducible infarction sizes with delineated boundaries for precise lesion characterization, ideal for modelling AIS. When considering treatment for AIS, the use of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) is a potential candidate due to their ability to improve endothelial function, modulate thrombogenesis, and attenuate inflammatory and oxidative stress damage4. In addition, it is unknown whether statins would reduce infarct size and blood-brain barrier (BBB) damage in a juvenile population5. This study aims to longitudinally assess stroke and BBB progression following the use of a statin in a juvenile photothrombotic rat stroke model using MRI and histology.Methods

A photothrombotic stroke model was induced in ten male Sprague Dawley rats (n = 10, 5 weeks old, 145±15g). Stroke was confirmed on DWI/T2W MRI. 5 rats received 20 ml/kg of Atorvastatin via peritoneal injection post imaging on day 0 and 5 rats received no treatment acting as a control. Quantitative MRI was performed at the hyperacute (Day 0), sub-acute (Day 2) and chronic stages (Day 7) after AIS following photothrombosis. All procedures were approved by The Animal Care Committee at the Hospital for Sick Children under the Canadian Council of Animal Care guidelines.Procedure: Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction, 2% maintenance at 1L/min). An incision was made along the scalp (no craniotomy) and a ring was placed on the ipsilateral hemisphere of the skull, centered between three identifiers (midline, lambda, and bregma), to restrict laser illumination. 2ml/kg Rose Bengal dye was injected through the tail vein. After 5 minutes a cold light source was used to illuminate the target area for 20 minutes with a light intensity of 150W.

MRI: A 3.0T MRI system (Philips Achieva 3.0 T TX) equipped with an 8-channel wrist coil was used to acquire all imaging data. The MRI protocol consisted of T2W, DWI, DCE, and was performed on all rats at all time points. The T2W protocol consisted of a standard 2D turbo spin echo (TSE) acquisition (TR/TE = 3,000/98 ms, FOV = 100 x 85 mm2, Matrix=168x142, pixel size= 0.28x0.28 mm, 5.6 pixels per mm, FA=90˚, number of slices=8, slice thickness=1 mm, number of slices=8). For DWI, images were obtained with a 2D TSE acquisition with an additional set of diffusion gradients (TR/TE=801/86 ms, FOV=100x85 mm2, Matrix=168x142, pixel size= 0.18x0.18 mm, 3.52 pixels per mm, FA=90˚, slice thickness=2 mm, number of slices=6, b=0, 1000). DCE images were obtained using a 3D gradient echo, T1-weighted dynamic acquisition (TR/TE = 6.3/2.2 ms, temporal resolution: 6.1 s, field of View = 100 X 85 mm2, matrix = 168 X 142, number of slices: 10, number of dynamics per slice: 40, slice thickness = 1 mm, volumes: 40, time = 4:20 min).

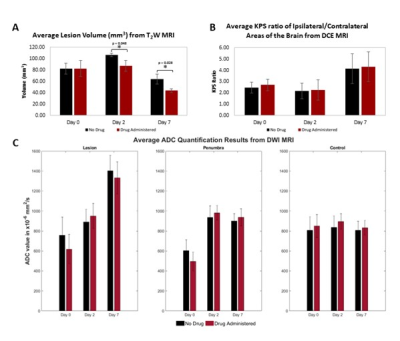

Analysis: The image analysis platform 3D slicer (3D slicer, USA) was used to analyze the T2W images. The lesion was segmented manually for each slice where the lesion was present to calculate the lesion volume. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps were created from DWI images using MATLAB. ADC values (units of x10-6mm2/s) were calculated within regions of interest (ROIs) including the lesion, penumbra, and control area in the contralateral hemisphere. Permeability maps, expressed as permeability surface area product (KPS) in units of mL/ 100 mg/min, were generated from DCE images in MATLAB using the Patlak model6. Permeability values were calculated within the high-intensity lesion area for a single coronal slice and a homologous contralateral control area. The KPS ratio between the control and lesion area was calculated to control for variance between scans. Student’s t-tests, Benjamini-Hochberg corrected for multiple comparisons (α level of 0.05), were conducted to compare quantitative values between control and atorvastatin groups.

Results

The measured T2W lesion volume was significantly reduced in statin groups, compared to the control, on both day 2 (p = 0.048) and day 7 (p = 0.028) following AIS. The ADC values and KPS ratios showed no significant changes between groups over time. The results can be seen in Figure 1.Conclusion

We have characterized longitudinal stroke and BB changes following the use of statin in juvenile rats using a photothrombotic stroke model. Our results show a reduction of infarct size in the statin group when compared to the control signifying less brain damage. However, there was no significant effect on BBB progression, with persisting BBB disruption up to day 7. Further studies are needed to substantiate these findings due to the limited sample size.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] DeVeber GA, MacGregor D, Curtis R, Mayank S. Neurologic outcome in survivors of childhood arterial ischemic stroke and sinovenous thrombosis. J Child Neurol. 2000;15(5):316-324. doi:10.1177/088307380001500508

[2] Tsze DS, Valente JH. Pediatric Stroke: A Review. Emerg Med Int. 2011;2011:1-10. doi:10.1155/2011/734506

[3] Wester P, Watson BD, Prado R, Dietrich WD. A photothrombotic `ring’ model of rat stroke-in-evolution displaying putative penumbral inversion. Stroke. 1995;26(3):444-450. doi:10.1161/01.STR.26.3.444

[4] Zhao J, Zhang X, Dong L, Wen Y, Cui L. The Many Roles of Statins in Ischemic Stroke. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2014;12(6):564-574. doi:10.2174/1570159x12666140923210929

[5] Fernández-López, D., Faustino, J., Daneman, R., Zhou, L., Lee, S. Y., Derugin, N., ... & Vexler, Z. S. (2012). Blood–brain barrier permeability is increased after acute adult stroke but not neonatal stroke in the rat. Journal of Neuroscience, 32(28), 9588-9600.

[6] Patlak CS, Blasberg RG. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. Generalizations. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1985 Dec;5(4):584–90

Figures