1951

Does sex matter? A 1H MRS metabolic study in a mouse model of transient ischemic stroke1Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), Lausanne, Switzerland, 2Center for Biomedical Imaging, EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland, 3Laboratory of Functional and Metabolic Imaging, EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland

Synopsis

Keywords: Stroke, Preclinical

A considerable sex bias exists in preclinical research, with studies on male animals outnumbering those in females, yet several preclinical rodent studies of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) reported that infarct volume is smaller in females than in males. As the neurochemical profile greatly evolves after stroke, the present study aimed to evaluate whether the neurochemical profile is modified differently between male and female mice post tMCAO. We found that baseline values apart from taurine show no differences as previously reported. However, a difference in the metabolic profile between male and female mice becomes visible after tMCAO.Introduction

Stroke is the second most common cause of death and the third leading cause of disability worldwide1. One in five women between the ages of 55 and 75 will have a stroke, compared to one in six men2. Many sex-related differences in stroke causes, outcomes, and response to treatment were reported in clinical studies3,4. In preclinical research, there is still a considerable sex bias with studies on male animals outnumbering those on females. In particular, this bias is most prominent in neuroscience research5. Coherently, the use of female rodents in stroke research is quite sparse6,7. Several preclinical rodent studies of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) reported that infarct volume is smaller in females than in males8–10. Recent 1H MRS metabolic studies indicated a difference only in taurine concentration between healthy control male and female mice11,12. As the neurochemical profile greatly evolves after stroke13, the present study aimed to evaluate whether the post-MCAO neurochemical profile is differently modified between male and female mice.Methods

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane. Regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) was measured by Laser-Doppler flowmetry (Perimed AB, Sweden). Transient focal cerebral ischemia was induced by occlusion of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) as described elsewhere14,15. rCBF was maintained below 20% of the baseline for 30 minutes, after which the occluding filament was withdrawn to allow reperfusion. Occlusion was considered successful if rCBF decreased by at least 80% of the start value and reperfusion if the rCBF rose above 50% of the baseline within 10 min after filament removal.MRS data were acquired either a week or a day before MCAO surgery (baseline), then 3h and 24h post MCAO in a 9.4T scanner using a home-built 1H-quadrature surface coil located on top of the mouse’s head. T2W images were acquired and B0 inhomogeneity was corrected at the voxel located at the striatum where the lesion is expected to form (2 × 1.8 × 2 mm3, 7.2 μL). 1H MRS spectra were acquired using SPECIAL pulse sequences16 (TE/TR = 2.8/4000 ms, 200 ms acquisition time in 15 × 16 scans). Metabolite concentrations were calculated using LCModel-based fitting routine17. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA in OriginPro software.

Results and discussion

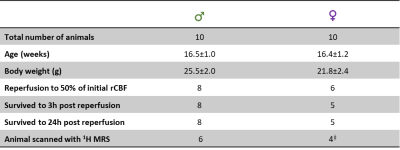

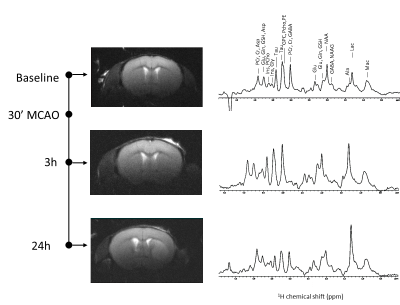

A summary of the physiological parameters as well as those related to the tMCAO surgery is presented in Figure 1. Four females and two males were excluded from the study as their rCBF did not rise above 50% of the baseline within 10 min after filament removal. One female that reperfused well did not survive till 3h post reperfusion. Among the animals that could be included in the study, 6 males and 4 females were scanned with 1H MRS.A typical set of data including T2W images as well as the 1H spectra measured at a voxel located in the striatum is presented in Figure 2. While the lesion is not observed at 3h post reperfusion, a clear change in metabolite concentrations is depicted in the 1H MRS data.

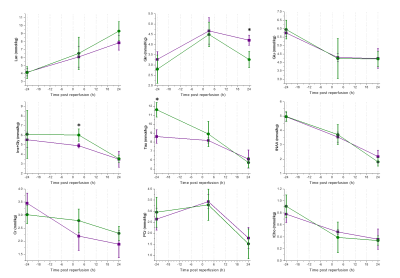

Selected metabolites’ concentration as well as their time evolution for both male and female mice are presented in Figure 3. As previously reported at baseline level11,12, the only significant difference was found for taurine concentration. However, there was no difference in the level of this metabolite after reperfusion. We found that in tMCAO animals, the concentrations of glutamine at 24 h as well as the sum of inositol and glycine at 3 h were significantly different between male and female mice. Note that overall, the trend of the change in metabolite concentrations is similar to previously reported values in male rodents13.

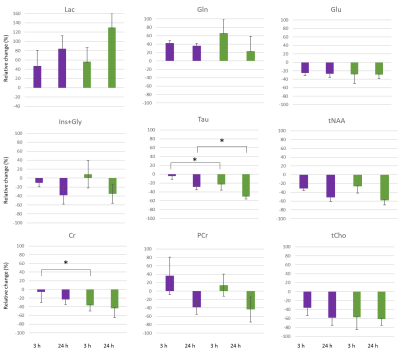

For each individual animal that was scanned over the 3 time points, we defined the relative change from baseline level (i.e., the relative difference between the value at a specific time point and the baseline value), and reported the mean values of these changes in Figure 4. This parameter would give indications regarding the dynamics of the metabolic evolution. The relative change of taurine was significantly higher in males compared to females. Interestingly, while at every time point, the average concentration of creatine was not different between males and females, the relative change was found significantly different at 3h post reperfusion, suggesting differences in the metabolic dynamics between male and female mice.

Our findings emphasize that sex-related differences can be evidenced after invoking stroke, and indicate that including female rodents in preclinical studies may bring new insights in translational research, together with a better understanding on the sex-related differences between stroke in woman and men.

Conclusion

Between male and female mice, no differences in the metabolic profile are observed at baseline, apart from taurine. However, differences in metabolite concentration and evolution become evident after invoking the ischemic stroke.Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Rolf Gruetter and Prof. Jean-Noël Hyacinthe for supporting this collaboration and for the fruitful discussion. Dr. Analina Hausin and Dr. Stefanita Mitrea for their assistance in the animal preparation, as well as the CIBM Center for Biomedical Imaging, co-founded and supported by Lausanne University Hospital, University of Lausanne, École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne, University of Geneva and Geneva University Hospitals.References

1. Johnson W, Onuma O, Owolabi M, Sachdev S. Stroke: a global response is needed. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(9):634-634A. doi:10.2471/BLT.16.181636

2. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2016 Update. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38-e360. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350

3. Turtzo LC, McCullough LD. Sex Differences in Stroke. CED. 2008;26(5):462-474. doi:10.1159/000155983

4. Ospel JM, Schaafsma JD, Leslie-Mazwi TM, et al. Toward a Better Understanding of Sex- and Gender-Related Differences in Endovascular Stroke Treatment: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2022;53(8):e396-e406. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000411

5. Beery AK, Zucker I. Sex bias in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;35(3):565-572. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.002

6. Baskerville TA, Macrae IM, Holmes WM, McCabe C. The influence of gender on ‘tissue at risk’ in acute stroke: A diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging study in a rat model of focal cerebral ischaemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36(2):381-386. doi:10.1177/0271678X15606137

7. Faber JE, Moore SM, Lucitti JL, Aghajanian A, Zhang H. Sex Differences in the Cerebral Collateral Circulation. Transl Stroke Res. 2017;8(3):273-283. doi:10.1007/s12975-016-0508-0

8. Manwani B, Bentivegna K, Benashski SE, et al. Sex Differences in Ischemic Stroke Sensitivity Are Influenced by Gonadal Hormones, Not by Sex Chromosome Complement. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35(2):221-229. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2014.186

9. Brait VH, Jackman KA, Walduck AK, et al. Mechanisms Contributing to Cerebral Infarct Size after Stroke: Gender, Reperfusion, T Lymphocytes, and Nox2-Derived Superoxide. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(7):1306-1317. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2010.14

10. Liu F, Li Z, Li J, Siegel C, Yuan R, McCullough LD. Sex Differences in Caspase Activation After Stroke. Stroke. 2009;40(5):1842-1848. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.538686

11. Larson SN, Tkac I, Differences between neurochemical profiles of male and female C57BL/6 mice. Proc. Int. Soc. Mag. Res. Med. 2018 https://archive.ismrm.org/2018/1368.html

12. Duarte JMN, Do KQ, Gruetter R. Longitudinal neurochemical modifications in the aging mouse brain measured in vivo by 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neurobiology of Aging. 2014;35(7):1660-1668. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.01.135

13. Lei H, Berthet C, Hirt L, Gruetter R. Evolution of the Neurochemical Profile after Transient Focal Cerebral Ischemia in the Mouse Brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29(4):811-819. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2009.8

14. Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20(1):84-91. doi:10.1161/01.STR.20.1.84

15. Castillo X, Rosafio K, Wyss MT, et al. A Probable Dual Mode of Action for Both L- and D-Lactate Neuroprotection in Cerebral Ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35(10):1561-1569. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2015.115

16. Mlynárik V, Gambarota G, Frenkel H, Gruetter R. Localized short-echo-time proton MR spectroscopy with full signal-intensity acquisition. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2006;56(5):965-970. doi:10.1002/mrm.21043

17. Provencher SW. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1993;30(6):672-679. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910300604

Figures