1941

Demonstration of brain temperature as a parameter for treatment stratification after acute ischemic stroke1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology & Emory University, Atlanta, GA, United States, 2Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, United States, 3Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, United States, 4Department of Neurology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, United States, 5Petit Institute for Bioengineering and Bioscience, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Stroke, Thermometry

Prior research has demonstrated the benefits of endovascular thrombectomy after acute ischemic stroke. Despite improvements in surgical techniques, patient selection for thrombectomy remains challenging. In this case study, we explored the utility of brain temperature to accurately predict infarct core and salvageable tissue to stratify patients for thrombectomy. We observed infarct volume estimated from temperature maps was more similar than CT perfusion to the true infarct volume identified using apparent diffusion coefficient images from diffusion weighted imaging. Temperature-based ischemia-to-infarct ratio showed better patient stratification than conventional methods, suggesting the complementary use of brain temperature in patient selection after ischemic stroke.

Introduction

Endovascular thrombectomy 6 – 24 hrs after acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is an effective strategy for improved patient outcomes.1,2 Efficacy of thrombectomy, however, is limited to patients with a ratio of ischemia-to-infarct volume>1.8 and small infarct volume (<70 mL)2,3 to avoid complications.4 In the acute setting, computed tomography perfusion (CTP) is routinely used to estimate the volume of infarct and salvageable tissue. The use of CTP alone can underestimate infarct size due to recanalization either before or after intervention in patients with large vessel occlusion,5 and improved patient stratification for thrombectomy is an immediate clinical need. Previous studies have reported elevated brain temperature in ischemic brain regions in AIS patients.6,7 In a non-human primate model of AIS, transient temperature changes in infarct and salvageable tissue were significantly different 24 hrs after onset,8 and infarct volume was significantly correlated with infarct temperature.9 Here, we demonstrate the applicability of brain temperature for patient selection for thrombectomy after AIS and compare to conventional methods using CTP alone.Methods

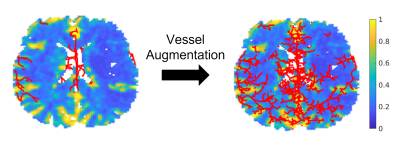

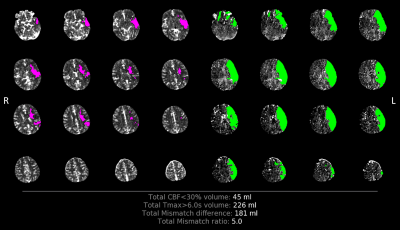

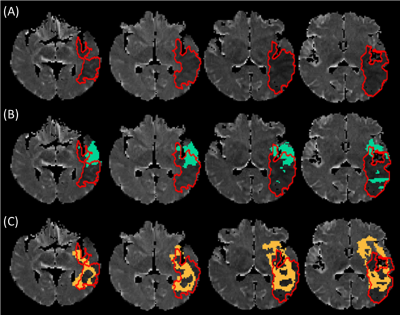

In this retrospective study, imaging data was obtained from an AIS patient (58 years old male) who underwent thrombectomy but with failed reperfusion (final thrombolysis in cerebral infarction score = 0). CT data was acquired with a Discovery CT750 HD (GE Healthcare) and MR data using a 3 T MR scanner (TIM Trio, Siemens Healthcare). Intracranial vascular anatomy was determined using helical CTA (120 kVp; 500 mAs; resolution=0.5×0.5×0.6 mm3). For perfusion-related parameters (e.g., relative cerebral blood flow [rCBF] or time to maximum [Tmax]), CTP was collected from 2 contiguous slabs at 5 mm sections per slab (80 kVp; 145 mAs; pixel spacing=0.47×0.47 mm2). Post-contrast T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid-gradient-echo images (TR/TI/TE=1900/900/2.52 ms; flip angle (FA)=9°; resolution=1.0×1.0×1.0 mm3) were used to define tissue structures. Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI; TR/TE=4400/91 ms; FA=90°; resolution=1.2×1.2×6.0 mm3) acquired ~12 hrs after admission was used to identify the true (final) infarct volume.All imaging data were resampled and transformed to T1-weighted image space using SPM 12.10,11 Automated user-independent software (RAPID)12 was used to extract deconvolved perfusion-related parameters from CTP data. Skull-stripped13 CTA was preprocessed with image contrast enhancement, Gaussian smoothing, and a vessel enhancement diffusion filter.14 Arteriovenous structures were segmented automatically using Rivulet.15 Arteries and veins were separated manually using NeuTube.16 Using MR tissue structure and segmented vasculature from CT, patient-specific brain temperature maps were estimated using a previously reported biophysical brain model.17 rCBF images were used as a weight map for each slice to augment additional vessel tree branches using a rapidly exploring random tree algorithm (Figure 1).18 Cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) was reduced by 26% in voxels with rCBF<30% (initial infarct from CTP) from the model-estimated value, as previous literature reports ~26% reduction in CMRO2 in infarct compared to the same region in the contralateral hemisphere.19 Temperature thresholds for ischemic (infarct + salvageable tissue) and salvageable tissue were empirically determined from contralateral temperatures fitted to a Gaussian distribution (mean = μ, standard deviation [SD] = σ); ischemic tissue: temperature>μ+σ, salvageable tissue: temperature>μ+2σ, and infarct: μ+σ<temperature<μ+2σ. The ischemia-to-infarct ratio was acquired from the temperature map and compared to the ratio acquired using RAPID ([volume of voxels with Tmax>6s]/[volume of voxels with rCBF<30%). rCBF-identified and temperature-identified infarct volumes were compared to the true infarct volume from manually segmented apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) DWI images using the Dice similarity coefficient (DSC).20

Results

Empirically derived temperature thresholds (lower limit) for ischemic regions and salvageable tissue were 37.31 °C (=μ+σ) and 37.51 °C (=μ+2σ), respectively, and the infarct region was empirically defined as 37.31 °C<temperature<37.51 °C (Figure 2A). Mean ± SD of temperatures across salvageable and infarcted tissue voxels identified from the model-predicted temperature map were 37.63 ± 0.10 °C and 37.40 ± 0.06 °C, respectively (Figure 2B). The ischemia-to-infarct ratio using empirical temperature values was 1.4 and infarct volume was 70.2 mL. This patient received thrombectomy based on a RAPID ratio>1.8 and infarct volume<70 mL (Figure 3, conventional inclusion criteria2,3) but resulted in no reperfusion after intervention. In comparison, temperature-based thresholds (ratio<1.8 and infarct volume>70 mL) would have excluded this patient from thrombectomy. DSC between ADC-identified true infarct and initially predicted infarct volume from rCBF was 0.14 and from the predicted temperature map was 0.28 (Figure 4).Discussion

In this case study, retrospective imaging data from a patient with failed reperfusion after thrombectomy was used to facilitate brain temperature predictions. Mean temperatures of infarct and salvageable tissue from our model predictions were consistent with previous in vivo measurements using MR chemical shift thermometry (37.63 °C and 37.30 °C in salvageable and infarct tissue, respectively,6 compared to 37.63 °C and 37.40 °C from our model-predictions). Furthermore, temperature-based patient stratification may have excluded this patient from thrombectomy, in contrast to the conventional RAPID-based decision with inclusion criteria currently used in clinical management (ischemia-to-infarct ratio>1.8 and infarct volume>70 mL).2,3 Comparisons with true infarct volume using ADC images demonstrate brain temperature may predict the final infarct volume more accurately than rCBF.Conclusion

We demonstrate temperature-based stratification as a potential method of patient selection for thrombectomy after AIS. Brain temperature may be a complementary parameter to current perfusion-based stratification parameters.Acknowledgements

This research was supported, in part, by an American Heart Association predoctoral fellowship to D.S. (Award ID: 909342).References

1. Nogueira RG, Jadhav AP, Haussen DC, et al. Thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke with a mismatch between deficit and infarct. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(1):11-21.

2. Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, et al. Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):708-718.

3. Laughlin B, Chan A, Tai WA, Moftakhar P. RAPID automated CT perfusion in clinical practice. Pract Neurol. 2019;2019:41-55.

4. Maïer B, Desilles JP, Mazighi M. Intracranial hemorrhage after reperfusion therapies in acute ischemic stroke patients. Front Neurol. 2020;11:599908.

5. John S, Hussain SI, Piechowski B, Dogar MA. Discrepancy in core infarct between non-contrast CT and CT perfusion when selecting for mechanical thrombectomy. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg. 2020;22(1):8-14.

6. Karaszewski B, Wardlaw JM, Marshall I, et al. Measurement of brain temperature with magnetic resonance spectroscopy in acute ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2006;60(4):438-446.

7. Karaszewski B, Wardlaw JM, Marshall I, et al. Early brain temperature elevation and anaerobic metabolism in human acute ischaemic stroke. Brain. 2009;132(4):955-964.

8. Sun Z, Zhang J, Chen Y, et al. Differential temporal evolution patterns in brain temperature in different ischemic tissues in a monkey model of middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:980961.

9. Dehkharghani S, Fleischer CC, Qiu D, Yepes M, Tong F. Cerebral temperature dysregulation: MR thermographic monitoring in a nonhuman primate study of acute ischemic stroke. Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38(4):712-720.

10. Collignon A, Maes F, Delaere D, Vandermeulen D, Suetens P, Marchal G. Automated multi-modality image registration based on information theory. Inf Process Med Imaging. 1995;3(6):263-274.

11. Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Diffeomorphic registration using geodesic shooting and Gauss–Newton optimisation. Neuroimage. 2011;55(3):954-967.

12. Straka M, Albers GW, Bammer R. Real‐time diffusion‐perfusion mismatch analysis in acute stroke. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;32(5):1024-1037.

13. Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29(3):162-173.

14. Bernier M, Cunnane SC, Whittingstall K. The morphology of the human cerebrovascular system. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39(12):4962-4975.

15. Liu S, Zhang D, Liu S, Feng D, Peng H, Cai W. Rivulet: 3D neuron morphology tracing with iterative back-tracking. Neuroinformatics. 2016;14(4):387-401.

16. Feng L, Zhao T, Kim J. neuTube 1.0: a new design for efficient neuron reconstruction software based on the SWC format. Eneuro. 2015;2(1):1-10.

17. Sung D, Kottke PA, Risk BB, et al. Personalized predictions and non-invasive imaging of human brain temperature. Commun Phys. 2021;4(1):1-10.

18. LaValle SM, Kuffner Jr JJ. Randomized kinodynamic planning. Int J Robot Res. 2001;20(5):378-400.

19. Gersing AS, Ankenbrank M, Schwaiger BJ, et al. Mapping of cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen using dynamic susceptibility contrast and blood oxygen level dependent MR imaging in acute ischemic stroke. Neuroradiology. 2015;57(12):1253-1261.

20. Dice LR. Measures of the amount of ecologic association between species. Ecology. 1945;26(3):297-302.

Figures