1927

Connectomics Biomarkers of Gulf War Illness1Emory University, Atlanta, GA, United States, 2UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, fMRI (resting state)

Around 200,000 veterans of the 1991 Gulf War (GW) suffer from GW illness (GWI). GWI is a poorly understood chronic medical condition, characterized by multiple symptoms. One factor that hampers mechanistic investigations into GWI is that there is considerable heterogeneity in symptoms across the GW veteran population. Only one case definitions of GWI addresses this heterogeneity. The Haley GWI case definition addresses this by further breaking down GWI into three main syndrome variants (Syn1, Syn2, and Syn3) based on factor analysis of symptoms presented by GWI veterans. In this study, we extracted rsfMRI connectomics biomarkers for different syndromes of GWI.INTRODUCTION

Around 200,000 veterans (up to 32% of those deployed) of the 1991 Gulf War (GW) suffer from GW illness (GWI). GWI is a poorly understood chronic medical condition, characterized by multiple symptoms indicative of brain function deficits in cognitive, affective, perception and nociception domains[1-6]. Epidemiologic and animal studies have associated GWI with exposure to neurotoxic chemicals such as nerve agents, organophosphate pesticides and pyridostigmine bromide, all of which are cholinergic stimulants that inhibit acetylcholinesterase [1, 7, 8]. One factor that hampers mechanistic investigations into GWI is that there is considerable heterogeneity in symptoms across the GW veteran population. This could reflect the underlying heterogeneity in both exposure to neurotoxic substances, as well as genetic predisposition or resistance to neurotoxicity [9, 10]. Only one of the validated case definitions of GWI addresses this heterogeneity. The Haley GWI case definition addresses this by further breaking down GWI into three main syndrome variants (Syn1, Syn2, and Syn3) based on factor analysis of symptoms presented by GWI veterans [8, 11]. Resting state fMRI (rsfMRI) is an uniquely useful brain imaging technique in that it can probe multiple brain function domains at the same time [12]. In this study, we employed machine learning to extract neuroimaging biomarkers of each of the syndromes of GWI.METHODS

57 GWI veterans (mean age 49.4 yrs.) of which 18 had GWI Syn1 (GWS1), 23 had Syn2 (GWS2) and 16 had Syn3 (GWS3), and 29 veteran controls (mean age 49.8 yrs.), of which 15 (DVC) were deployed in the GW theater, 14 (NVC) were not deployed, were scanned in a Siemens 3T MRI scanner using a 12-channel Rx head coil. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the protocol approved by the local Institutional Review Board. RsMRI data were acquired with a 10-min whole-brain gradient echo EPI (TR/TE/FA = 2000/24ms/90°, resolution = 3mm x 3mm x 3.5mm). RsfMRI preprocessing steps included attenuation of signal related to subject-motion and physiological responses using the ICA-AROMA technique[13], followed by regression-based removal of white matter fMRI signal, and spatial smoothing with FWHM = 6mm isotropic Gaussian kernel. The preprocessed rsfMRI data for each subject was parcellated based on the Brainnetome atlas [14] to construct a 276-node graph formed by Pearson correlation between different Brainnetome ROI-averaged time-series. Previous studies show that DVC themselves exhibited signs of neural impairments compared to the NVC, though not to the same extent as those considered syndromic [15]. Further, GWS2 exhibit lot more debilitating neurological symptoms in all brain function domains than the other two, whereas GWS1 and GWS3 exhibited more impairment than each other in different functional domains. Hence, we employed ordinal multiclass support vector machine (SVM) techniques [16-18] to perform three 3-groups SVMs, classifying the veterans into GWS1/GWS2/GWS3, DVC and NVC. We also performed a 4-group SVM by classifying the veterans into (GWS1 and GWS3), GWS2, DVC, and NVC. The generalizability of the SVM classifications were tested with 5-fold cross-validation.RESULTS & DISCUSSION

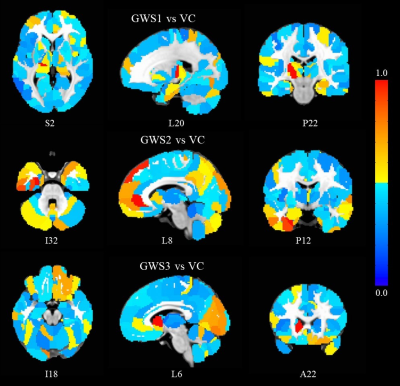

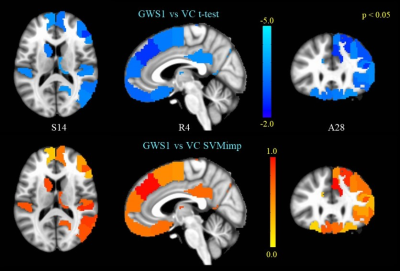

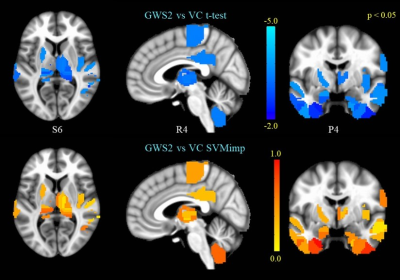

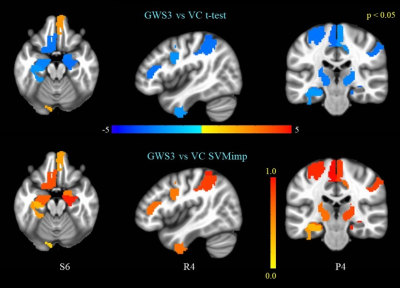

The 3-class SVM classifications were able to predict GWVs as belonging to GWS1/DVC/NVC, GWS2/DVC/NVC, and GWS3/DVC/NVC with 83%, 94%, and 71 % accuracy respectively. Further the 4-class SVM was able to distinguish between (GWS1+GWS3)/GWS2/DVC/NVC with 85% accuracy. The SVMs provided importance scores (SVMimp) to to each edge (between-node connection) in the 276-node Brainnetome graphs based on the contribution to the classification. Figure 1 shows the hubness of each node determined by normalized sum of the importance scores of all its edges, in distinguishing GWS1/GWS2/GWS3 from veteran controls (VC = DVC + NVC). It is easily apparent that there is a considerable amount of heterogeneity in brain FC impairments between the groups. Subthalamic nucleus (STN) seems most impaired in GWS1. Examining the STN-FC map of GWS1(Figure 2) reveals STN FC with medial frontal, premotor and sensorimotor areas are most decreased in GWS1 compared to VC, which are consistent with deficits in these functions seen in GWS1 [1-3, 8] On the other hand, Figure 1 shows that ventral anterior cingulate (vACC) and prefrontal, and limbic areas seem most impaired in GWS2. Examining vACC FC maps (Figure 3) shows deficits in fronto-striatal, fronto-temporal and default mode network FC in GWS2 compared to VC. This is consistent impairments in executive function, memory, limbic functions in GWS2 [1, 3, 7, 8]. Figure 1 also shows that ventral caudate exhibit the most severe impairments in FC in GWS3. Examining FC maps of ventral caudate reveals impairments in parietal-premotor, motor, somatosensory and memory networks in GWS3 which are consistent with deficits in these functions [1-3, 7]. Conclusions We were able to extract connectomics based biomarkers for different GWI syndromes. Our results reveal both similar and unique impairments in FC among these syndromes, which are consistent with their neurological symptoms.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Office of Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, through the Gulf War Illness Research Program under Awards No.W81XWH-16-1-0744 (PI Gopinath), and No. W81XWH-21-1-0237 (PI Gopinath). Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense.References

1. Binns, J.H., et al., Report of Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses, D.o.V. Affairs, Editor. 2014, U.S. Government Printing Office: Boston, MA.

2. Hom, J., R.W. Haley, and T.L. Kurt, Neuropsychological correlates of Gulf War syndrome. Arch Clin Neuropsychol, 1997. 12(6): p. 531-44.

3. Calley, C.S., et al., The neuroanatomic correlates of semantic memory deficits in patients with Gulf War illnesses: a pilot study. Brain Imaging Behav, 2010. 4(3-4): p. 248-55.

4. Gopinath, K., et al., FMRI reveals abnormal central processing of sensory and pain stimuli in ill Gulf War veterans. Neurotoxicology, 2012. 33(3): p. 261-271.

5. Moffett, K., et al., Word-finding impairment in veterans of the 1991 Persian Gulf War. Brain Cogn, 2015. 98: p. 65-73.

6. Toomey, R., et al., Neuropsychological functioning of U.S. Gulf War veterans 10 years after the war. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 2009. 15(5): p. 717-29.

7. Bhardwaj, S., et al., Single dose exposure of sarin and physostigmine differentially regulates expression of choline acetyltransferase and vesicular acetylcholine transporter in rat brain. Chem Biol Interact, 2012. 198(1-3): p. 57-64.

8. Haley, R.W., T.L. Kurt, and J. Hom, Is there a Gulf War Syndrome? Searching for syndromes by factor analysis of symptoms. JAMA, 1997. 277(3): p. 215-22.

9. Haley, R.W., S. Billecke, and B.N. La Du, Association of low PON1 type Q (type A) arylesterase activity with neurologic symptom complexes in Gulf War veterans. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 1999. 157(3): p. 227-33.

10. Nakanishi, M., et al., The ratio of serum paraoxonase/arylesterase activity using an improved assay for arylesterase activity to discriminate PON1(R192) from PON1(Q192). J Atheroscler Thromb, 2003. 10(6): p. 337-42.

11. Iannacchione, V.G., et al., Validation of a research case definition of Gulf War illness in the 1991 US military population. Neuroepidemiology, 2011. 37(2): p. 129-40.

12. Laird, A.R., et al., Behavioral interpretations of intrinsic connectivity networks. J Cogn Neurosci, 2011. 23(12): p. 4022-37.

13. Pruim, R.H., et al., ICA-AROMA: A robust ICA-based strategy for removing motion artifacts from fMRI data. Neuroimage, 2015. 112: p. 267-77.

14. Fan, L., et al., The Human Brainnetome Atlas: A New Brain Atlas Based on Connectional Architecture. Cereb Cortex, 2016. 26(8): p. 3508-26.

15. Spence, J.S., et al., Using a white matter reference to remove the dependency of global signal on experimental conditions in SPECT analyses. Neuroimage, 2006. 32(1): p. 49-53.

16. Hsu, C.W. and C.J. Lin, A comparison of methods for multiclass support vector machines. IEEE Trans Neural Netw, 2002. 13(2): p. 415-25.

17. Zhou, X. and D.P. Tuck, MSVM-RFE: extensions of SVM-RFE for multiclass gene selection on DNA microarray data. Bioinformatics, 2007. 23(9): p. 1106-14.

18. Schölkopf, B., C.J.C. Burges, and A.J. Smola, Advances in kernel methods : support vector learning. 1999, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. vii, 376 p.

Figures

(top panel) GWS1 vs VC t-test on subthalamic nucleus FC.

(bottom panel) SVM importance scores for edges correspond to the STN-FC map

(top panel) GWS2 vs VC t-test on ventral anterior cingulate FC.

(bottom panel) SVM importance scores for edges correspond to the vACC-FC map

(top panel) GWS3 vs VC t-test on ventral caudate FC.

(bottom panel) SVM importance scores for edges correspond to the ventral caudate FC map