1921

Identification of brain alterations specifically associated with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy using multi-modal MRI and multivariate analysis1Neuroimaging Unit, Scientific Institute IRCCS Eugenio Medea, Bosisio Parini, Italy, 2Department of Brain and Behavioral Sciences, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy, 3Child Psychopathology Unit, Scientific Institute IRCCS Eugenio Medea, Bosisio Parini, Italy, 4Paediatric Radiology and Neuroradiology Department, V. Buzzi Children’s Hospital, Milano, Italy, 5NeuroMuscular Unit, Scientific Institute IRCCS Eugenio Medea, Bosisio Parini, Italy

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Genetic Diseases

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) is a genetic disease caused by an abnormal dystrophin expression and it is often associated with other cognitive and behavioral impairments, which are an important confounding factor while investigating the effects of dystrophin abnormal expression in the central nervous system. We applied a Machine Learning based analysis to T1-weighted and Diffusion Tensor Imaging data of 36 subjects accounting also for their demographic, cognitive and behavioral profiles. DMD is specifically associated with a reduced microstructural integrity of long fiber bundles and a reduced cortical thickness of the motor cortex, cingulate cortex, hippocampus and insula.Introduction

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) is a genetic disease linked to the gene-X causing an abnormal dystrophin expression and is mainly associated with progressive muscular weakness, cardiomyopathy and respiratory insufficiency.Central nervous system involvement in DMD has been reported in previous MRI based studies(1,2), without accounting for the presence of comorbidities, such as cognitive impairment, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorders (ADHD) and obsessive compulsive behavior, which have been widely described in at least one third of DMD patients(3).

The aim of this study is to identify alterations in the central nervous system specifically associated with DMD performing a whole brain multimodal analysis implemented through a Machine Learning (ML) approach.

Methods

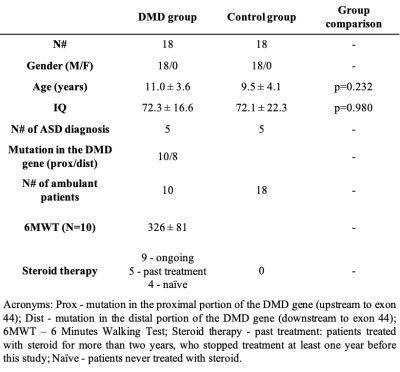

Eighteen DMD patients and 18 control subjects with similar demographic, cognitive and behavioral profiles were enrolled in this study (Table-1). The subject cognitive assessment included intelligence quotient (IQ) measurements (WPPSI-III, WISC-IV, or Griffiths scales), ASD evaluation (ADOS-2 test) and a thorough psychiatric and neurological assessment to exclude any other major impairments.The MRI acquisition protocol included T1-weighted 3D (voxel size 1x1x1 mm3, TR=8ms, TE=3.7ms, flip angle=8°), T2-weighted 2D (voxel size 1.5x1.5 mm2, slice thickness=1.5mm, TR=3000ms, TE=100ms) and DTI (4 b0 volumes, 8 directions at b=300 s/mm2, 32 directions at b=1100 s/mm2, voxel size=2×2mm2, slice thickness=2mm, TR=12s, TE=80ms) sequences.

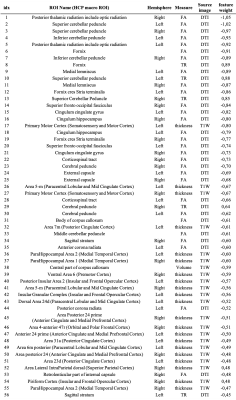

Cortical thickness (360 measures) and subcortical structure volume (40 measures) were computed from the T1w images using FreeSurfer and the HCP-MMP1 atlas(4) cortical parcellation. DTI images were processed using TORTOISE(5) software and FA (48 measures) and MD (48 measures) values were computed over 48 regions placed in the middle of the main fiber bundles.

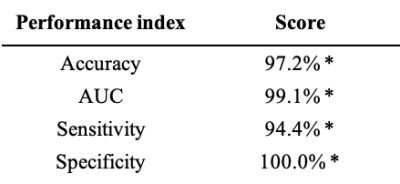

A linear regression model was used to correct the MRI features for age, IQ and ASD diagnosis. Subsequently, a T-test was performed with a significant threshold set to p<0.05 to select the most relevant features to be used in the classification experiment(6). A linear kernel SVM classifier (C=1) was used to discriminate between DMD patients and controls with a balanced leave-one-out cross validation procedure(7). Finally, the generative model associated with the linear classifier was computed to perform a “forward model” feature weight analysis and identify the most important features associated with DMD(8).

Results

Fifty-five features (21 cortical thickness measures, 1 volume measure, 29 FA measures and 5 MD measures) were selected by the preliminary feature selection procedure and used in the classification experiment.The linear classifier significantly discriminates between DMD patients and controls (table 2). The forward model weights were computed from the trained classifier (table 3); large magnitude values identify the most impaired features, while negative values indicate a reduction of the feature in DMD patients with respect to the controls. DMD mostly affects the microstructural integrity of long fiber bundles, as suggested by the larger weights associated with DTI derived measures indicating an FA reduction in the cerebellar peduncles (bilaterally), in the posterior thalamic radiation (bilaterally), in the fornix and in the medial lemniscus (bilaterally) (Figure 1). Forward model weights also indicate a pattern of cortical thickness reduction in DMD patients, mainly in the motor cortex, cingulate cortex, hippocampal area and insula (Figure 1).

Discussion

We used a ML approach to perform a multivariate and multi-modal analysis of the central nervous system in DMD patients and controls. In the control groups were also present subjects with ASD diagnosis and/or with cognitive impairment (i.e. IQ<70), allowing us to include some of the common comorbidities associated with DMD in the analysis as covariates.The high performances reported by the classification experiment suggest a direct relationship between the diagnosis of DMD, thus the related lack of dystrophin expression, and the integrity of the central nervous system. Further analyses showed a significant axonal damage in several WM fiber bundles, mainly characterized by reduced FA and increased MD, and a thickness reduction in the cerebral cortex.

Conclusions

We showed that a multivariate analysis including the DMD comorbidities in the control group allows the identification of new brain areas specifically associated with the diagnosis of DMD.Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Italian Ministry of Health ("Ricerca Corrente 2021-2022" grant to Denis Peruzzo) and by “5 per mille” funds for biomedical research.References

1. Preethish-Kumar V, Shah A, Kumar M, Ingalhalikar M, Polavarapu K, Afsar M, Rajeswaran J, Vengalil S, Nashi S, Thomas PT, Sadasivan A, Warrier M, Nalini A, Saini J. In Vivo Evaluation of White Matter Abnormalities in Children with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Using DTI. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020 Jul;41(7):1271-1278. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6604. Epub 2020 Jul 2. PMID: 32616576; PMCID: PMC7357653.

2. Doorenweerd N, Straathof CS, Dumas EM, Spitali P, Ginjaar IB, Wokke BH, Schrans DG, van den Bergen JC, van Zwet EW, Webb A, van Buchem MA, Verschuuren JJ, Hendriksen JG, Niks EH, Kan HE. Reduced cerebral gray matter and altered white matter in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2014 Sep;76(3):403-11. doi: 10.1002/ana.24222. Epub 2014 Jul 24. PMID: 25043804.

3. Pane M, Lombardo ME, Alfieri P, D'Amico A, Bianco F, Vasco G, Piccini G, Mallardi M, Romeo DM, Ricotti V, Ferlini A, Gualandi F, Vicari S, Bertini E, Berardinelli A, Mercuri E. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and cognitive function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: phenotype-genotype correlation. J Pediatr. 2012

4. Glasser, M.F.; Coalson, T.S.; Robinson, E.C.; Hacker, C.D.; Harwell, J.; Yacoub, E.; Ugurbil, E.Y.K.; Andersson, J.; Beckmann, C.F.; Jenkinson, M.; et al. A multi-modal parcellation of human cerebral cortex. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 536, 171–178.

5. Irfanoglu MO, Nayak A, Jenkins J, and Pierpaoli C. TORTOISEv3: Improvements and New Features of the NIH Diffusion MRI Processing Pipeline. In: Proceedings of the annual meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM 2017) 25th annual meeting, Honolulu, HI, abstract #3540

6. Saeys Y, Inza I, Larrañaga P. A review of feature selection techniques in bioinformatics. Bioinformatics. 2007 Oct 1;23(19):2507-17. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm344. Epub 2007 Aug 24. PMID: 17720704.

7. Poldrack, R.A.; Huckins, G.; Varoquaux, G. Establishment of best practices for evidence for prediction, a review. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 77, 534–540.

8. Haufe, S.; Meinecke, F.; Görgen, K.; Dähne, S.; Haynes, J.-D.; Blankertz, B.; Bießmann, F. On the interpretation of weight vectors of linear models in multivariate neuroimaging. NeuroImage 2014, 87, 96–110.

Figures