1916

Single-shell diffusion MRI for imaging white-matter microstructure in COVID-19: DTI vs. correlated diffusion imaging1Rotman Research Institute, North York, ON, Canada, 2Department of Medical Biophysics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Department of System Design Engineering, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 4Sunnybrook Research Institute, Sunnybrook Health Science Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada, 5Department of Psychology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 6Institute of Biomedical Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, Correlated diffusion imaging, single-shell diffusion MRI.

This study examines microstructural white-matter differences between self-isolated COVID-19 patients and controls using correlated diffusion (CDI) and diffusion-tensor imaging (DTI) based on single-shell acquisitions. Correlated diffusion imaging reveals microstructural differences between patients and controls in frontal, olfactory, and cerebellar regions previously unseen with diffusion-tensor imaging. Our results suggest CDI as a feasible single-shell imaging technique that is sensitive to distinct impacts in various brain regions.Introduction

An important cause of morbidity in COVID-19 has been infection of the central nervous system (CNS) (1). Existing studies that examine white-matter (WM) microstructure in COVID-19 largely focus on hospitalized patients (2–4). One study found reduced mean diffusivity (MD) and axial diffusivity (AD) in the superior fronto-occipital fasciculus, the external capsule, and the corona radiata of patients (3). Another study found lower intracellular volume fraction in the corona radiata of hospitalized patients (2–4). COVID-19 leading to mild respiratory illness can still induce significant CNS damage (5), however neurological COVID-19 effects in individuals that self-isolated with mild respiratory illness remain understudied. Hence, our work focuses on self-isolated patients. Our previous work demonstrated widespread diffusion abnormalities in WM microstructure between patients and controls (6). In this work, the feasibility of single-shell diffusion MRI approaches, including correlated diffusion imaging (CDI), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and the recently proposed orthogonal-tensor decomposition DTI (DT-DOME) (7), are compared for uncovering microstructural COVID-19 effects. CDI is a single-shell compatible method that successfully enhanced the sensitivity of diffusion MRI to cancerous prostate tissue (2), and is now applied for the first time to brain imaging.Methods

ParticipantsHere we report findings from 39 self-isolated COVID-19 positive (COVID+) patients (mean age: 42.1, 72% female), and 14 controls (mean age: 43, 64% female) who had flu-like symptoms but tested negative for COVID-19 (COVID-).

Diffusion MRI Data

Diffusion MRI data acquisition occurred on a Siemens Prisma 3T system with 5 b=0 and 34 b=700s/mm2 volumes at TR = 4.3 s, TE= 62ms, 2mm isotropic resolution, with 2 sets of phase-encoding directions to allow distortion correction. A T1-weighted image was also acquired with 1 mm isotropic resolution.

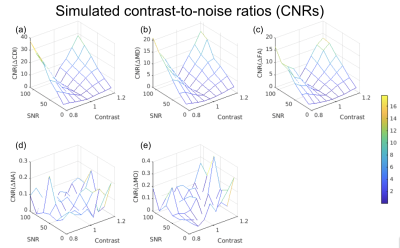

Simulations

We simulated diffusion signals according to our acquisition protocol, with two types of ground truth for anisotropic diffusion (norm of anisotropy (NA) = 1): (1) healthy WM, and an MD of 0.6 mm2/s; (2) diseased WM, with MD ranging from 80% to 120% of healthy tissue. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) ranged from 10 to 110 based on Rician noise. We computed the Contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) = mean(effect size) / std(effect size) across all SNRs, where effect size represented the measured difference in diffusion metric between healthy and diseased WM.

Data Processing

All data sets were manually checked for quality, then corrected for eddy currents and susceptibility-related distortions using TOPUP, respectively. DTI parameters included: fractional anisotropy (FA), MD, AD, radial diffusivity (RD); DT-DOME parameters included the norm (NA), and mode of anisotropy (MO). All were obtained using the single-compartment DTI-model fit (8) of the b=0 and 700 s/mm2 shells. The CDI maps (log(CDI)) were computed as the product of all diffusion images for a given participant using an in-house MATLAB script, using the same data.

Statistical analysis

FSL’s TBSS was used for voxelwise statistical analysis of all data. Voxelwise differences for each parameter were assessed for patients versus controls. Each map was then subjected to significance testing using FSL randomise with 500 permutations. Region of interest (ROI) comparisons were made between groups.

Results

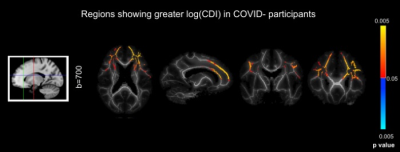

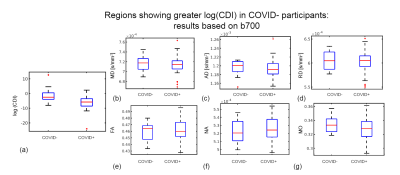

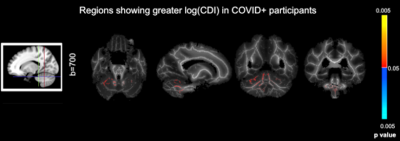

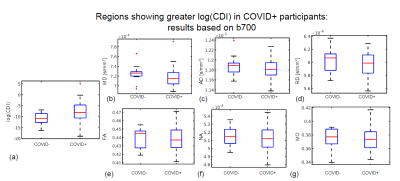

Simulations predicted a superior CNR in log(CDI) than DTI to detect abnormalities driven by MD increase (Fig. 1). Using DTI parameters, we observed no significant difference between the baseline COVID+ and COVID- groups. However, we observed significant group differences through CDI values. Widespread frontal effects were evident in regions where log(CDI) was greater in the COVID- group than the COVID+ group (Fig. 2). These regions included the corona radiata and superior longitudinal fasciculus. Moreover, log(CDI) was greater in the COVID+ group than the COVID- group in the cerebellum (Fig. 4). Boxplots of DTI metrics averaged over a union of significant CDI ROIs demonstrate a general lack of significant group differences (Fig. 3 and Fig. 5).Discussion and Conclusion

This work demonstrates considerable sensitivity advantages of CDI over traditional DTI. The simulations demonstrate that CDI can be viewed as in principle inversely proportional to MD, however with far greater sensitivity to disease. In the simulations, the disease effect is modeled as a difference in MD alone, thus FA is less affected by the condition. Based on the simulations, we hypothesized that when pathology is defined by changes in diffusivity as opposed to anisotropy, in-vivo CDI performance would be superior to DTI.Our finding that log(CDI) is greater in the COVID- group in frontal regions may reflect blood-brain barrier leakage and enlargement of the extracellular spaces ((9); (10)). Effects in the olfactory region observed in this work may be explained by the olfactory bulb being the most likely entry point for SARS-CoV-2 in the brain (11)2; (12).

Our finding that log(CDI) is greater in the COVID+ group in the cerebellum at the initial visit may be explained by debris accumulation following immune cell infiltration (9). Histological studies have found that in COVID-19, immune cell infiltration is most prominent in the cerebellum (13); (14).

The regions of interest that were implicated in this analysis are consistent with NODDI results from the literature (4). Future work will involve using NODDI with the current dataset and comparing results to the existing CDI and DTI analyses.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the CIHR and Sunnybrook Research Institute for their support.References

1. Iadecola C, Anrather J, Kamel H. Effects of COVID-19 on the Nervous System. Cell. 2020 Oct 1;183(1):16–27.e1.

2. Wong A, Glaister J, Cameron A, Haider M. Correlated diffusion imaging. BMC Med Imaging. 2013 Aug 8;13:26.

3. Lu Y, Li X, Geng D, Mei N, Wu PY, Huang CC, et al. Cerebral Micro-Structural Changes in COVID-19 Patients - An MRI-based 3-month Follow-up Study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Aug;25:100484.

4. Huang S, Zhou Z, Yang D, Zhao W, Zeng M, Xie X, et al. Persistent white matter changes in recovered COVID-19 patients at the 1-year follow-up. Brain [Internet]. 2021 Dec 16 [cited 2022 May 11]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/brain/advance-article/doi/10.1093/brain/awab435/6464331

5. Fernández-Castañeda A, Lu P, Geraghty AC, Song E, Lee MH, Wood J, et al. Mild respiratory SARS-CoV-2 infection can cause multi-lineage cellular dysregulation and myelin loss in the brain. bioRxiv [Internet]. 2022 Jan 10; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.07.475453

6. Chen J. J., Chad J. A., Ji X., MacIntosh B. J., Gilboa A., Roudaia E., Sekuler A.B., Lam B., Heyn C., Black S. E., Graham S. J. COVID19 effects on brain tissue microstructure: Longitudinal study of self-isolated cases using diffusion MRI. ISMRM. 2021.

7. Chad JA, Pasternak O, Chen JJ. Orthogonal Moment Diffusion Tensor Decomposition Reveals Age-Related Degeneration Patterns in Complex Fibre Architecture. Neurobiol Aging [Internet]. 2021 Feb 3; Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0197458020304310

8. Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. FSL [Internet]. Vol. 62, NeuroImage. 2012. p. 782–90. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015

9. Lee MH, Perl DP, Steiner J, Pasternack N, Li W, Maric D, et al. Neurovascular injury with complement activation and inflammation in COVID-19. Brain [Internet]. 2022 Jul 5; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awac151

10. Malerba P, Agabiti Rosei C, Nardin M, Gaggero A, Chiarini G, Rossini C, et al. Early microvascular modifications in patients previously hospitalized for COVID-19: comparison with healthy individuals. Eur Heart J. 2021 Oct 14;42(Supplement_1):ehab724.3387.

11. Serrano GE, Walker JE, Tremblay C, Piras IS, Huentelman MJ, Belden CM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Brain Regional Detection, Histopathology, Gene Expression, and Immunomodulatory Changes in Decedents with COVID-19. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol [Internet]. 2022 Jul 11; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jnen/nlac056

12. Xydakis MS, Albers MW, Holbrook EH, Lyon DM, Shih RY, Frasnelli JA, et al. Post-viral effects of COVID-19 in the olfactory system and their implications. Lancet Neurol. 2021 Sep;20(9):753–61.

13. Colombo D, Falasca L, Marchioni L, Tammaro A, Adebanjo GAR, Ippolito G, et al. Neuropathology and Inflammatory Cell Characterization in 10 Autoptic COVID-19 Brains [Internet]. Vol. 10, Cells. 2021. p. 2262. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/cells10092262

14. Matschke J, Lütgehetmann M, Hagel C, Sperhake JP, Schröder AS, Edler C, et al. Neuropathology of patients with COVID-19 in Germany: a post-mortem case series. Lancet Neurol. 2020 Nov;19(11):919–29.

Figures